Difficulty plays a big role in keeping players motivated and engaged. It is a source of satisfaction. But why is that, how does it work and how can we design good challenges, and avoid frustration?

This article was first published on https://medium.com/@ricardo.valerio/make-it-difficult-not-punishing-7198334573b8

Difficulty plays a big role in keeping players motivated, engaged and, unintuitively, in marketing. Some games have it better designed than others. Some design it even to make it satisfyingly hard, like Dark Souls. But others have it poorly designed, with a very high difficult bar set from the very start, or none to little difficulty altogether, combined with too steep or too shallow difficulty increase. So how do we go about designing good difficulty?

The first thing that we need to do is to define difficulty.

What is difficulty?

Difficulty is the amount of skill required by the player to accomplish a goal or progress through the game experience. It can be as simple as jumping from one platform to another, killing a character, defeat a boss fight — which could be designed to respectively be easy, medium and hard to accomplish.

Difficulty goes hand in hand with the challenge presented and the skill of the player related to that challenge and the game. Present a too high challenge for a low skilled player and it becomes a hard barrier from which players can turn away from; present a too low challenge for high skilled players, and it wont be interesting for them.

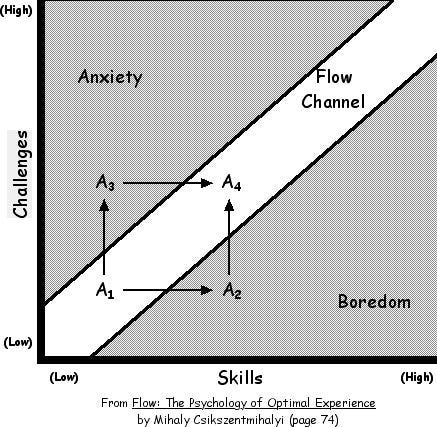

The optimal difficulty is one in which the challenge presented is always slightly higher than the skill of the player when he first encounters it, so defeating the challenge provides a climax, small or big, and satisfaction. This provides for an optimal flow state, where the player knows accomplishing the goal is possible, and investing energy will provide for a satisfying resolution.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a hungarian psychologist, proposed the following graph that defines flow as the channel where there is an optimal level of skill vs challenge..

From Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, by Mihály Csikszentmihály

Difficulty is the amount of skill required by the player to accomplish a goal or progress through the game.

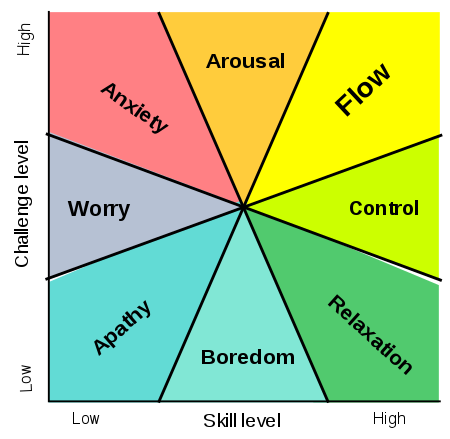

Later on, he proposes a more detailed mental map, matching certain areas of skill and challenge to specific mental states.

Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(psychology)

As we can see here, a difficult challenge for an average skilled player will at first provoke arousal — the player knows it’s hard right now, but it is within his grasp, and he only needs to become a little more skilled , or perhaps acquire an ability that is key for the challenge, and become skilled at it. But eventually, a player will be in full control of the challenge, as riding a bike. And over time, it will become a somewhat relaxing, or boring, activity. So it’s important that in order to keep players engaged, more difficult challenges must be presented, or alternatively, different ways of accomplishing goals and avoiding having a single solution for resolving them. So if the player does defeat a challenge, it is always possible to increase their mastery by going back and trying to make it better.

And this leads us to motivation.

Motivation

So what drives someone to perform an activity? We can separate motivations in two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. When someone is intrinsically motivated, he performs the activity because he likes it, it is satisfying, regardless. An extrinsically motivated person, however, will perform for an external reward — praise, fame, an item, an achievement. Because of this, an extrinsically motivated player needs external factors, but on the other hand, an intrinsically motivated player has his own flame of desire to perform a task. This is important to understand, because whenever possible the primary motivations that should be focused on are the intrinsic ones.

This leads us to Self-Determination Theory. The theory states that humans have three fundamental needs, as described in it’s wikipedia page:

Autonomy, or “to be causal agents of one’s own life and act in harmony with one’s integrated self”

Competence, or “seek to control the outcome and experience mastery”

Relatedness, or “ the universal want to interact, be connected to, and experience caring for others”

Directly connected to skill is competence. It is important for the player to feel he can use his mastery and feel he can control the outcome.

Designing good difficulty

We know that difficulty will derive from the challenge presented and the player’s skill. Skill is a combination of mental and physical effort and capabilities, which culminate in mastery. And players can vary heavily in skill, depending on their previous experiences, motor skills, cognitive capabilities in the game context, etc. But on the other hand, challenge is easier to define, and can be designed to require an increasing amount of mastery.

What is a good challenge?

The problem mostly lays in defining good challenges. Consider these two boss fights:

The boss will randomly kill a player every 5 to 10 seconds without any kind of warning

The boss will every 10 seconds place a deadly void zone on the player’s feet, that will explode after 3 seconds and kill anyone on top of it

The first one is very punishing, and there is nothing the player can do about it, no matter how much skill he has and earns. But if we look at the second boss, we have many elements that provide for a great challenge and promote learning:

There are cues

The player can react to it

There is feedback

The player can, therefore, increase his skill in dealing with it

Consider riding a bicycle. First times, we are clumsy, lose balance, go slowly. Over time, we focus rather more on the environment than the process of riding the bike itself, because we already are familiar with it, we learned the required techniques for each activity, such as pedaling, balancing, braking, turning, and our skill is high. Same with video games. A good activity should be learnable, to such an extent that it can become mostly automatic, so we can focus on reacting to the environment.

A good challenge should present cues, allow a reaction and provide feedback, so when the player fails, he will feel that he could have done better. This will foster learning and increase of skill.

If we look at any boss fight in World of Warcraft, we can see they are carefully designed to always provide cues, feedback and allow the player to react. All the mechanics are carefully set in the fight to make it possible to accomplish without it being overly frustrating. The goal is always within reach, and practice takes the player closer to defeating it. Difficult raid bosses have a set of abilities, and sometimes phases in the fight, that as they are defeated get the raiding team steps closer to defeating the challenge. This has a potent effect, because as players get closer to their goal, tension rises and builds towards a climax. And after hitting the climax, it provides a great deal of satisfaction — even euphoria and shouting, I have witnessed it first hand with my own guild.

A challenge doesn’t need to be solved in the first attempts. But there should be a sense of progress.

Even in games as difficult as Super Meat Boy, where a player dies multiple times before clearing a level, players remain engaged. There are clear visual cues of the threats, there is a great deal of feedback, and after death the player character respawns quickly. With each attempt, the player learns what works better. Perhaps timing, or jumping closer or farther from an edge, etc.

When Flappy Bird went viral in 2014, players were raging with the difficulty of the game. A quick search reveals a plethora of videos with raging players. And yet, it went viral, and people were relentlessly trying to get better at it. The fact that cues were presented and the player could react means that there is a chance to become skilled. And it is in fact so hard, that just passing a few pipes can be a reason for bragging and a great sense of one’s growing mastery.

Artificial vs Designed difficulty

We can add difficulty in two ways: artificial or designed. Designed difficulty is when you design a boss with a certain set of abilities, perhaps adding or removing depending if you are doing a raid with 10 or 25 players, or a hard mode. It is difficulty which requires learning new skills or using them in a certain way, as opposed to just performing better with existing ones.

Generally speaking, artificial difficulty is about changing stats. Designed difficulty is about introducing or combining different mechanics, which force the player to learn and master specific skills.

Examples of artificial difficulty are increasing health, defenses, attacks, number of enemy characters or reduce the time limit if it exists. Examples of designed difficulty are the boss getting a new ability, different kinds of enemies joining the fight or requiring coordination with other players.

Artificial difficulty is cheap. It’s easier to tweak than designed difficulty. But at the same time, it might feel cheap for the player. If by going hard mode only changes stats, then the player wont get anything new out of it — unless it challenges his assumptions and forces him to be creative or rethink his strategy. For example, a boss that beats much harder and for longer periods might force the players to rotate their survival abilities carefully; and in team efforts, it might even lead them to coordinate survival abilities.

To make a point, imagine a game where you have only one single enemy character that appears with increasingly amounts of health and attack. Now imagine one where the enemy characters vary in abilities. The first would become boring faster, and the second one has more chances for using skills differently.

As with everything, moderation is key. Use both and combine them to present the best challenge for the player.

But it’s not just boss fights

While boss fights are in many games a point of climax, and therefore usually are taken more seriously when it comes to difficulty, it doesn’t stop there — in fact, it doesn’t even start there. Setting the difficulty starts right from the beginning of the game. As simples as learning movements, learning to jump, use a skill. The initial game experience of the player is crucial to spark the desire to play and keep playing.

In Super Mario Bros, the player starts with an empty scenario, and is left with the only option which is to move. Then he is presented with a cube with an interrogation mark, which will likely trigger curiosity and try to interact with it. Soon after, the first NPC appears, he looks angry and moves towards the player — there are signs he is a threat, and the player needs to react to it. If he touches it, Mario will die — feedback — and the player learned he can’t touch them by walking to them — he has to try something else. The most likely step afterwards will be to try to avoid or jump on top of it, as to smash it, and there will be feedback that the player successfully defeated the challenge presented — his skill level now allows him to deal with these type of NPCs successfully.

From the start, the player feels he is learning.

Wrapping it up

When designing good challenges, it is important that the player is able to learn from it, and increase his mastery. In order to do that, we should present cues, visual, audio, vibration, etc, that signal the player something is about to happen. This creates an opportunity to react, and eventually prove one’s mastery. And finally, there should be feedback. With each attempt, the player will become more skilled, defeat the challenge and become satisfied.

If the player fails, you want to have him feel there was something better he could have done, and not leave him frustrated and helpless.

Avoid having single solutions to defeating a challenge and let play sessions vary — this allows the player to get better, as opposed to a static solution. Make it a difficult challenge, but within reach. And avoid making it punishing.

Conclusion

We went through a definition of difficulty, what drives players, and what is an optimal difficulty level that promotes flow. Allowing the player to learn is fundamental, which ultimately drives progress, and gives a sense of competence and autonomy. And in the end, players will want to seek more challenges.

So when it comes to difficulty, make it hard, but not punishing.

Stay tuned

Stay tuned for followups on this series on game design, where I will explore other aspects of game design. Follow me on Medium.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like