Analysis of extended fiction techniques used in ICEY, a part of my series of blog posts with sections from my Honors Thesis on extended fiction in game design.

Video games, as an art form, are always a collaborative effort between at least 2 parties: the developer[1], and the player. Without the developer, be it a single person or a 300-employee studio, the game wouldn’t exist. Without the player, the game couldn’t perform as a piece of art. This is an endlessly fascinating relationship caused by the interactive nature of the medium. Within this collaboration, there are many non-diegetic positions the developer can traditionally fulfill: the storyteller, the toymaker, the referee, the dungeon master, etc. But on occasion, developers choose to engage in a diegetic relationship with the player, morphing the friendly relationship from artist to audience to one of rivalry and contention. This is another example of folding traditionally non-diegetic elements, in this case the developer, into the diegetic realm of the game.

The idea of the developer being the rival to the player, of being in an antagonistic relationship with the player, is a fascinating but common one. John “TotalBiscuit” Bain stated his view of single player games as this: “I view single player games as competitive… I view it as the notion of competing with the developer’s challenges, the things that the developer has prepared for me.” (Bain)

At its most basic, the purpose of a game is to create a set of challenges for the players entertainment, and then give them a toolkit of actions that, if performed in some correct sequence, will result in overcoming the challenge. In some games there is only one way to complete a challenge; other games offer multiple different strategies a player can execute to complete a given challenge. This notion hearkens back to the traditional table top role-playing game model, with a “Game Master” or “Dungeon Master” who is “the person who organizes or directs the story and play in a role-playing game” (Game Master) and players who compete against the challenges the game master has set up for them. Most players opt to tackle the challenges head on through traditional in game mechanics, but some players find much more enjoyment in subverting the creator’s plans by pushing the limits of the presented ruleset for a given game. In Creative Player Actions in FPS Online Video Games, the author discusses these kinds of behaviors as “creative player actions” and “creative innovations”;

Play is not just "playing the game," but "playing with the rules of the game" and is best shown in the diversity of talk, the creative uses of such talk and player behavior within the game, plus the modifications of game technical features… as in any human performance, creativity of execution is the norm… This creative subversion of game rules occurs consistently in the many debates over "cheating" within the game…. what is consistent is the bending of conventional game rules, as we have seen in this example, which can easily be viewed as a creative innovation within the game. (Wright)

In some games players can, through experimentation with the toolbox they are given, find a unique combination of in-game actions to perform that went totally unpredicted by the game’s designer. These creative player actions often undercut the intended skill check[2] and associated challenge the game was meant to provide. Players who are likely to engage in creative player actions typically enjoy this breaking of rules. These players are referred to as “Transgressive Players” (Aarseth), and the psychological motivations of transgressive players are explained by a section of Progress in Reversal Theory;

For example, conforming to the rules and rituals of some club that one is honored to be a member of can be a pleasure in itself, as can defying the rules of some petty authority or bureaucracy which appears to be restricting one’s activities unnecessarily. Conversely, failure to conform in the conformist state or failure to defy in the negative state will both contribute some degree of displeasure to the overall hedonic tone at the time in question. (Cowles)

One of the most famous (and comedic) examples of creative player actions can be found in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. The player can, at any point in the game, pick up and move around items within the game world and drop them wherever they want. The player can also, at any time, attempt to steal items from NPCs in the game. If they are caught doing so by an NPC, they are then confronted and punished for their attempted theft. But, if the player places a pot or basket over the head of all the present NPCs, their line of sight is totally cut off and they cannot detect the player stealing items from them. This leads to humorous instances where the transgressive player is casually robbing a merchant, while the merchant stands obliviously, acting normally with a kettle covering his head (Figure 2). This also removes all risk and challenge from the situation, undermining the developers intended challenge and risk/reward system involved with stealing.

Figure 2, Screenshot from The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim |

When a transgressive player can execute creative player actions, the result tends to break the immersion of the player, reminding them of the artificiality of the digital realm they’re interacting with. These situations draw the player out of the experience, pulling them from full immersion in a well simulated world to a non-immersed state with an obviously digital simulation. Traditionally these exploits are seen as disruptions to the game’s intended narrative, as they subvert the presentation of conflict intended to give plot and tone to the world the player interacts with. Indeed, the interactive nature of video games themselves provides difficulty in explicitly conveying narratives, as stated in A Case Study in the Design of Interactive Narrative: The Subversion of Narrative;

“The difficulty is that the exercise of interactive choice and a conscious volition can disrupt the immersion into narrative and story. In comparison to reading a book or watching a movie, some disruption of the narrative experience is inevitable. (Bizzocchi)

However, in some games, especially those in which the developer assumes a diegetic competitive role towards the player, the opportunities for creative player actions are often a bait-and-switch and create more immersion for already defiant players who attempt them. Players think they’ve found a loophole, a way to exploit the game that the developer didn’t consider, but it’s actually a trap laid by the developer to then return fire on the player for trying to circumvent the game’s logic. The developer has thought through the exploits the player might try and placed faux opportunities at likely points to bedevil them[ZS1] . They really aren’t catching the transgressive players acting unpredictably; they’re forming outcomes around things they anticipate the transgressive player to do, things the player might think are unpredictable. They’re folding what would usually be considered as non-diegetic exploits of the ruleset of the game into a diegetic position in the narrative. These exploits become diegetic maneuvers of the player against a diegetic game master, expanding the game narrative beyond the traditional on-screen plot elements into a player/dungeon master competitive narrative around game rule experimentation.

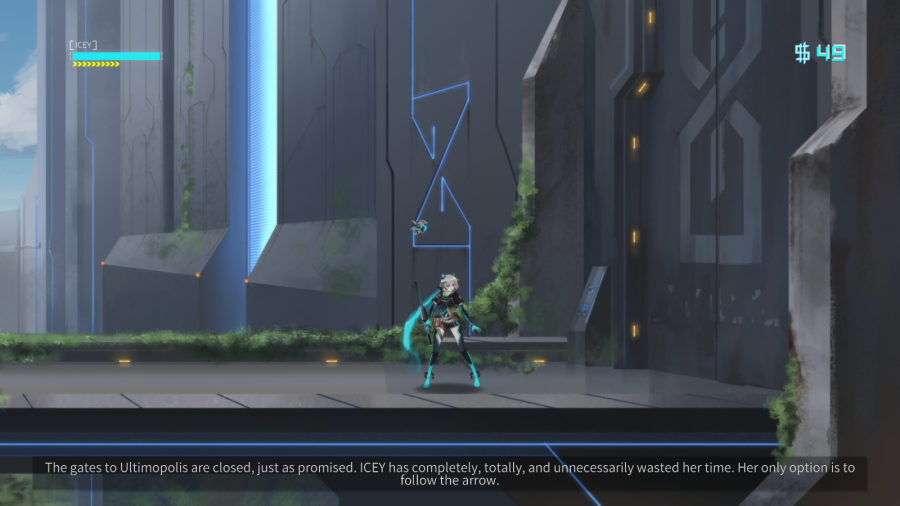

One of the best games that successfully exemplifies this relationship is ICEY. ICEY is a side scrolling brawler that relies on a very simple directional arrow system and a guiding narrator to direct the player where to go. The entire game can be played following the arrow, fighting enemies and experiencing the story of the titular main character in the “correct” way. The player can also choose to deviate from the arrows and explore at any time, and the game will acknowledge the transgressive player’s “disobedience”. The game’s narrator will make sarcastic, disparaging comments about the player, and the game will lead the player to weird secrets and present a wholly different experience. These “unintended paths” lead the player to unfinished levels, rooms with videos of prototype versions of the game, and continuous dialogue from the narrator about how much harder video game players make his life because of their insistence on testing the boundaries of the game instead of just playing it like it was meant to be played. The developer of ICEY designed the game specifically to tempt players into veering off the intended path so he could express his frustration with this habit players have in regular games, creating a metanarrative around this concept about the rigors of game development with an uncooperative audience. The game’s description on Steam states:

ICEY is a Meta game in disguise. The narrator will constantly urge you in one direction, but you must ask, "Why? Why am I following his directions? Why can't I learn the truth about this world and ICEY's purpose here?" Fight against his tyranny and uncover what's really going on for yourself! (Buy ICEY)

This purposefully challenges players to rebel against the game, it’s narrator, and ultimately, it’s developer, pushing the normal player to become transgressive. Narrators in games and other mediums are often perceived as the author themselves, being that “The narrator is always either a character who narrates or the author” (Alber). ICEY’s narrator is the game’s lead developer. “Fight against his tyranny” is not a call to fight against the tyranny of the voice the player is hearing, but the tyranny of the game, the tyranny of the rules the developer has set in place. It is a call to fight the rules and systems the developer prepared, the purposeful design and well-planned challenges they laid out, the carefully prepared story they penned for the player’s enjoyment. The object of the player’s crusade becomes the intent to try overturning the original design and taking control of the game’s world.

This very explicitly brings the game’s player and developer into a diegetic struggle for control. The narrative stops being about the adventures of the protagonist characters in the game and becomes a faux competition between developer and player, with the player defiantly competing against the developer they believe is antagonizing them, and the developer playing the part of the authoritative opposing force to actively encourage the player to explore and discover. This clever design philosophy rewards players not with just the traditional rewards inherent to overcoming a challenge in a game through intended actions, but a more intense reward that comes with the need for creative innovations through gameplay. As stated by Bain, “One of the things I really enjoy about this game is trying to outsmart the developer… and the discovery that …the developer has outsmarted me, not the other way around. That is a very joyful feeling indeed” (Bain). The experience of being rewarded for cleverness and exploration is one that doesn’t rely on fast reflexes or clever strategy, but on ingenuity. The enjoyment comes not from quick combos or good aim, but in being acknowledged as thoughtful enough to find hidden rewards and think independently of developer hand holding. In ICEY, the sarcastic insults prompted by disobedience are a thinly veiled reward to the player, an acknowledgement of respect from the developer to the player for uncovering the secrets of the game.

Furthermore, the creator of ICEY offers a critique to players who do dig far enough into his game; knowing that players who persist in creative gameplay actions are most likely ones who have done so before and will do so again, he offers up a frustrated dialogue about how the audience will disparage a game that they can find a way to exploit.

In reality, it’s very difficult to make a game, and it’s very easy for problems like this to appear… Unknowingly, 10 years flew by in the blink of an eye. With all the effort I spent, I think a few scattered bugs or missing features are entirely acceptable… Games are about entertainment. Don’t place too much value on a few mishaps here and there. (“Icey”)

What the developer does here is masterful; he presents situations in which he pretends as if the player has found a bug or exploit in the game, but really, it’s an intended experience in the game to push players who do find one of these situations into a clearer understanding of the frustrations experienced by game developers. It takes what is usually a peak behind a curtain into a disenchanting, immersion-ruining scene, and turns it into an immersive, personal moment between developer and player.

The execution of this design technique is dissectible into three parts. First, the game must present a “correct” or “intended” way of playing the game. Second, the game must have opportunity, whether explicitly encouraged or implicit, to stray from the “intended” route through the game. It is important to note that this encouragement can also take form in reverse psychology, and more often than not does, for purposes of comedic entertainment. Finally, the game must provide a feedback system of some kind, whether explicitly positive rewards (such as points or achievements) or sardonic rewards, such as annoyed responses from characters or the narrator, to encourage the player to keep playing and pushing boundaries.

Successful execution of this technique often involves layered subversions of video game tropes, in order to lead players into situations they expect to be able to exploit. The final step also requires acknowledgement of the player and/or developer as diegetic forces in the narrative. This provides motivation and immersion to the player in the experience, changing their creative player actions into the diegetic solutions in a game of wits against the developer , instead of breaking their immersion through unintended creative player actions. While diegetic adjustment is not explicitly required to execute this kind of intended creative player action focused game design, the purpose it serves in maintaining immersion is key to keeping players invested in a game with any sort of intentional narrative.

My personal experiences with this technique revolve around my game A Very Bad Clock Game, a game that I developed in my alternative game development class. The primary objective of the game is to drop a ball onto the hands of a real time clock in order to shepherd it into the goal. The game is intensely not fun ; the way I provided motivation to the player was through directly antagonizing them. I informed them that the game wasn’t fun or impressive in any way, that it’s a waste of their time, etc. This provided an interesting conflict in the game; not between the player and the rather tedious puzzles, but between the player and the developer (me) in who had the most patience. I found it best to approach the player early with the antagonistic relationship, since the game is intentionally encouraging its players to give up before they even find the extended fiction elements of the game.

Very few video games, or mediums of art in general, diegetically acknowledge the people who created them or their audiences. And even fewer of those games acknowledge in any way those who push at the limits of the software, finding their own creative ways of overcoming challenges. Games that not only acknowledge these methods of gameplay but are designed specifically to reward this type of play, provide unique narratives in the realm of games. Rather than just preventing transgressive player actions from breaking game systems, a task that consumes millions of assurance and bug fixing hours a year, the developers instead anticipate these actions and, in surprisingly good spirits, playfully put the players in their place. The games that account for a mass amount of gameplay variance with sarcastic commentary are perhaps the most honest expressions of the frustrations of the game development process that we have, and a playful acknowledgement of the creativity of players.

To read other entries in this series, check out my Gamasutra blog http://gamasutra.com/blogs/AustinAnderson/1028242/, or check out the full thesis on my website at http://austinanderson.online/thesis

[1] A game “developer” is a common term for anyone who works on the creation of a video game.

[2] A skill check is a term derived from tabletop RPG’s that refers to testing the abilities of a player.

Bain, John "Totalbiscuit", director.YouTube.YouTube, YouTube, 9 Dec. 2016,www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWtX1FQ_U64&t=1293s.

“Game Master.”Dictionary.com, Dictionary.com, www.dictionary.com/browse/game-master.

Aarseth, Espen. (2007). I Fought the Law: Transgressive Play and The Implied Player.

Cowles, Michael P., et al.Progress in Reversal Theory. North-Holland, 1988.

Bizzocchi, Jim, and Robert F. Woodbury. “A Case Study in the Design of InteractiveNarrative: The

�

“Buy ICEY.” ICEY on Steam, store.steampowered.com/app/553640/ICEY/

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like