“This is one of the things I’m most interested in," says Foddy. "As a game designer, the most fundamental problem you’re up against is that games don’t matter, they’re fake.”

In a recent video on Kotaku, Bennett Foddy completed his newest game, Getting Over It, in 34 minutes.

He was talking to Kotaku's Tim Rogers as he played, demonstrating the kind of mastery of technique and cool composure that comes with being its maker. And yet Foddy had only ever beaten Getting Over It once before, and even then it took him four and a half hours.

“In fact, in the weeks leading up to the Steam release I was trying to play through it to make sure there weren’t too many bugs, and I couldn’t beat it,” he says. “I kept getting right to the top and falling right down; some terrible falls, and not for lack of practice. I would feel myself tensing up and I’d be too careful and I’d tighten up and I’d lose it.”

Foddy’s own experience is illustrative of the continual tussle that plays in the heart of Getting Over It between its willfully infuriating game design and human psychology.

It’s a space in which a daunting situation causes you to choke, to fail to perform a move you’ve perfected in any other circumstance, and something Foddy has explored across such previous games as QWOP, CLOP, GIRP and Get On Top. In them he’s developed a language of playful frustration across different themes and "flavors", from awkward control schemes to hard-to-parse movement mechanics.

Putting down stakes

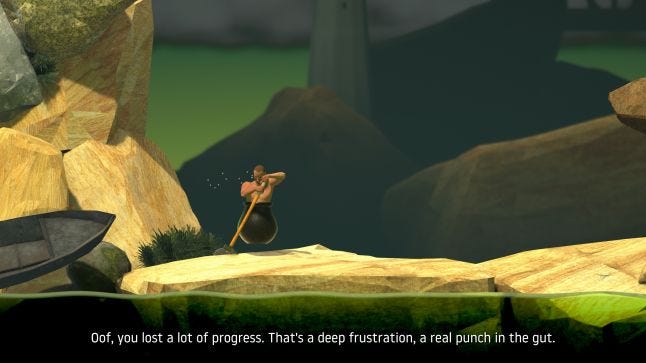

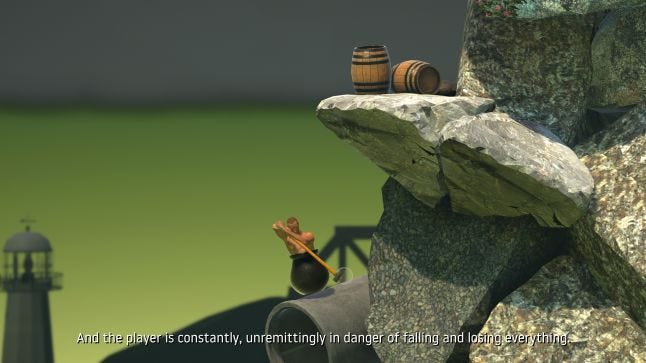

In Getting Over It, he explores the concept of having a lot to lose. The object is simple: to ascend a mountain. The thing is, you’re doing this as a man in a cauldron, using a hammer to drag and push him up sheer cliffs and across overhangs. Movement is difficult to regulate, and because you’re climbing a mountain, the threat of falling all the way back to the bottom is ever-present.

"This is one of the things I’m most interested in. As a game designer, the most fundamental problem you’re up against is that games don’t matter, they’re fake, they’re imaginary playgrounds."

If you’re looking to blame someone (or something) for Getting Over It, point your finger at Australia, where Foddy was born in 1978. Consoles like the NES took a long time to make their way to Australia because of protectionist trade restrictions and its electrical and TV signal standards, so like many of his generation, Foddy’s formative years were spent playing his ZX Spectrum and friends’ Commodore 64s. These 8-bit home computers hosted games which had directly evolved from the arcade and were often also unpolished or pushed the capabilities of the machines to their limits.

“They shared that with a disregard for fairness that comes from a culture of making games which, at the time, was very often teenagers in their bedrooms on contract to some publisher,” says Foddy, remembering Jet Set Willy, which would send you right back to the start if you died. “That’s almost invisible to you if you grew up playing arcade games because it was so ubiquitous, but it had a particular emotional flavor to it. You either get turned off by it when you’re five years old, or you learn to enjoy that taste and persevere and come back and try again.”

Foddy persevered, partly because he didn’t have many games, which were expensively imported from the UK. Meanwhile, in Japan and the US console games such as Dragon Quest and Mega Man 2 were beginning to feature save systems; for Foddy, this was the point when the punitive way games would send players back started to die.

“The flavor of being sent back gradually disappeared up to the point now where it’s this boutique thing,” he says. “People of a certain age still have that taste, or maybe everyone has it, but it’s been written out of the design orthodoxy.”

He points towards the outcry in August when it was announced that Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice would delete a save if the player died too many times, and at the way PC games will often be criticized for not having a quicksave/quickload function.

“But there are all these people walking around who enjoy being sent back in a game,” he says. “The glimmerings of that still being a living aesthetic is probably in Demon’s Souls. I was excited that this game deletes your money if you die twice in a row. For a lot of designers it was; whenever you see something that disproves a strongly held design orthodoxy it’s extremely exciting because it opens up new avenues for exploration.”

Getting Over It is an expression of that exploration. But as much as Foddy talks about the past in terms of Getting Over It’s heritage, it bucks it in one significant way. Its mountain is a single, continuous world, quite different to the standard discrete levels that came before it. That means that when you fall down, you watch every yard of ground you covered speed back past you, forcing you to resume from where you land.

Never be 'Game Over'

That’s resume, not restart. In GIRP you could fall off the mountain, but the game would restart, giving you a fresh attempt. “It’s emotionally different to having to pick yourself up again,” says Foddy.

Since it’s a continuation of your run, you don’t get to prepare yourself to start again. It’s true of Sexy Hiking, too, the game by Jazzuo which directly inspired Getting Over It.

“It’s divided into levels and even if I lose on level 10 and go back to level one I don’t have the same sensation of falling back from my current position all the way back to the beginning," Foddy says. "That’s something unusual. It has an effect on the meaning of it, right? It’s taking something away, even though in a structural way it’s the same as losing all your lives and restarting the game. There’s more of a sense of loss of something you had. It escapes your grasp more than if you just restart.”

He remembers watching a stream by Alex ’Baertaffy’ Larrabee in which he fell all the way back from near the summit to the start. “There was 15 seconds of dead air and I was really wondering what he was going to say, and he finally says, ‘Well, start again.’” Baertaffy is one of the premier Spelunky players, someone who is surely no stranger to the idea of starting over and over. “But I feel like in Spelunky, or any game that’s randomised, it’s a little bit less frustrating to die,” Foddy says, because you can blame the random level generation, though he appreciates that towards the end of a run, with the stakes – the time and effort you’ve invested in it – higher, you still get the same sense of stress and choking.

“This is one of the things I’m most interested in," says Foddy. "As a game designer, the most fundamental problem you’re up against is that games don’t matter, they’re fake, they’re imaginary playgrounds.”

When a game doesn’t matter, you sleepwalk through it. One solution is to drop other humans into the game, since they can enliven anything from noughts and crosses up. For single-player games it’s trickier. Narrative games can hook in character and emotion.

"whenever you see something that disproves a strongly held design orthodoxy it’s extremely exciting because it opens up new avenues for exploration."

“But skill games can’t. What I’m interested in is the feeling of developing stakes just from the effort you’re putting into the game,” Foddy says. “Somehow, when I’ve get high up a mountain I feel like I’ve accumulated something. There’s a moment in hiking or climbing when you look out and see how far you’ve gone, a sense you’ve accumulated progress. If you feel as though that can be taken away and you might have to do it again, that adds a sense of importance and high stakes that really transforms how you play the game.”

Another feature of the experience of falling down in Getting Over It is its commentary, which is voiced by Foddy himself. He discusses the game’s roots in Sexy Hiking as you play, and also acknowledges falls in a tone that balances supportive encouragement with slight goading edge.

“I have to say, my first take at writing the game was much more goading, much more sarcastic,” he admits. “But people already felt the strong emotions I wanted, and it was better to be more or less totally encouraging so I totally re-wrote it. But I still wanted a little touch of goading, a wink, if only because there’s some goading in genuine encouragement, right? If you were actually climbing a hill and you kept sliding back down and I was like, ‘Come on, you’ll get there!’ you’d be like, shut up! There’s no completely non-annoying way of encouraging someone. Even refusing to point out a failure is annoying in its own way.”

To play Getting Over It is to experience a very specific flavor of frustration, and in isolating it, it holds a candle to the spectrum of delicious frustration that videogames can generate. It’s another demonstration of Foddy’s uncanny ability to extract and synthesise emotion through mechanics, even if for him it came together in a slightly different way to his other games.

“This was an unusual process for me,” he says. “Usually I’m more exploratory, led by feel, tasting, like soup, making some judgments and adjusting. Here I knew what I wanted it to be from the beginning and it’s very close to that. That was nice, because I was trying to work fast to not give myself time to second-guess what I was doing. So it was efficient and reasonably free-spirited, and enjoyable in a way making games often isn’t because I had such a clear idea of what I was trying to make. I had a strong sense of how to produce the feelings I wanted.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like