Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

I discussed with developers and scientists their approach to design citizen science games. The conversation revealed some issues that the game industry could help solve.

In my first post, I introduced briefly a collection of games that let players contribute to science. They are called citizen science games. They are a collaboration between players and scientists to solve real scientific problems using gameplay or game elements. For my second post, I was about to focus on Project Discovery, which became one of the most successful citizen science project integrated in EVE Online, the biggest sci-fi themed massively multiplayer online game. I realised that I wanted to start by giving some context and after writing more than a thousand words with no mention of EVE, I decided to split the article into several articles. Today, I'll cover some differences in the approach scientists take to make their games depending on the question they are trying to answer. I'll raise some problems citizen science games are facing. I'll also show how the game industry, well, EVE Online so far, started tackling some of these problems.

Classification, interpretation, interaction

In her book, 'Knowledge games', Karen Schrier proposes a first categories of games. Two categories involve players processing and sometimes interpreting data. Cooperative contribution games invite players to classify, categorise or identify subjects, such as images, graphs, pictures. Often, the same subject is shown to many players and their answers are aggregated until a consensus is reached. In analysis distribution games, players must also provide a certain interpretation of the collected data. For this second category, Karen Schrier used the example of Apetopia. Players navigate through gates which colours match the colour of the sky, they avoid obstacles and collect coins. The players' choices of colour provide data on how the shades of colour are perceived by humans. Scientists train a neural network and try to model the collected data in order to develop better colour metrics.

Another category is related to players solving complex computational problems by forming heuristic strategies and sharing their strategies with other players, scientists and computers. Researchers then study how players came up with different solutions to develop algorithms that can be shared with, used and processed by computers. The interaction can be pretty simple in a game like Quantum Moves. Players drag and drop an atom, represented as a wave, to a target area. They have 20 seconds to move the atom, keep the shape stable and release. The trick is that the wave behaves in its own quantum way. In a game like Foldit, the number of tools and possible interactions with the protein is… let's just say huge and much more complex, for now.

Apetopia (left) uses player's perception to train a neural network. In Quantum Moves (right), players find solutions to quantum computer optimization.

'Casual' or not

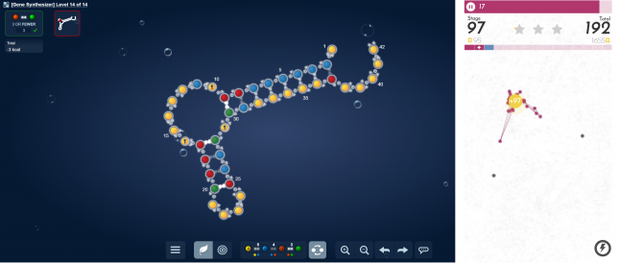

Some citizen science games are pretty 'hard-core' in the sense that they are knowledge intensive, have a big learning curve and/or have challenges that can take a long time for players to solve. This is the case of the browser game EteRNA, which lets players fold RNA molecules. The developers at Stanford just released a new series of puzzles aiming at making gene editing with CRISPR 'smarter and safer'. They are hoping to get around 100,000 RNA design solutions by the end of October. However, to contribute to this challenge, players must first earn 10 tools, and to earn these tools, they must complete about 120 puzzles. This represent hours (read weeks) of training. Benjamin Keep, PhD student in the learning sciences and former Eterna developer, explained to me that the community creates so much knowledge, this can become intimidating for new players:

"The project never "slows" down, so incoming volunteers have to play catch up, while experienced volunteers, who have logged thousands of hours and been doing this for 4+ years are already on to the next idea. This also means there's no way to contribute to the project casually".

Colony B, on the other hand, is much more 'casual'. In this mobile game, after a one minute tutorial, players start identifying clusters of bacteria, drawing circles around them before the timer expires. Learning more about these clusters allows researchers to figure out links between microbiome and human diseases. There is no perfect solution when clustering bacteria. Different solutions are good for the different criteria scientists use to estimate the quality of a cluster. When enough players have worked on a puzzle, the puzzle is removed. When I asked Jérôme Waldispuhl, associate professor in Computer Science at McGill University and project leader for Colony B and Phylo, about the level of scientific knowledge available in game, he explained that players can progressively learn about bacteria by unlocking badges. Their approach was to make the game accessible to a broad base of players and to gather scientific data early on:

"Our model is really benefiting of every participants. Even casual players answers make a difference."

My attempt to solve the last puzzle to unlock a second tool in EteRNA (left). My design doesn't match the expected design shown on the top left (But... how...??). On the other side (right), in Colony B my suggestion of cluster made me beat the best score within a few seconds of gameplay.

From subjects, to scientists, to experts

In citizen science games, players either become subjects participating in ‘online studies’, or they act as scientists. For example, there are currently two games advancing dementia and Alzheimer's research. Dementia decreases cognitive abilities in more than 45 million people today and there is no cure for it.

In Sea Hero Quest, players generate valuable data about the mental process of 3D navigation by sailing their boat through mazes and by firing flares towards a target. The game records anonymously player's sense of direction. Last year's result showed that sense of direction declines consistently across the lifespan. Having a record from millions of players of this normal decline could help develop better tests to diagnose dementia.

Volunteers don't provide data in Stall Catchers, but they help analyse the data. They look for stalls, clogged blood vessels that reduce blood flow in the brain. By reporting these stalls, they allow researchers to answer scientific questions about Alzheimer's disease quicker. In Reverse The Odds, which I describe a bit more further down, volunteers were also assisting researchers by examining cancer cells. In this 2 minutes video, Anne Kiltie, scientist at Cancer Research UK, explains that patients are confronted with difficult choice of treatments. Analysing slides in the lab can give ideas of what treatment might better work, but the analysis is time consuming. By bringing players to that process, scientists could look at far more samples than they could do in the lab.

"The citizen scientists are doing exactly the same thing as we are doing. They are determining whereas there are tumor cells in the sample, of the tumor cells, how many of them are actually stained up for the protein, and then how intensely are the stains."

Benjamin Keep explains that, in the case of EteRNA, some players, who sometimes call themselves "amateur scientists" (in the sense, non-professional / unpaid scientists) became experts in RNA design. A recent challenge was to design RNA molecules that could detect tuberculosis. While professional scientists in their lab couldn't design a molecule that worked well, players manage to detect a 3-gene signature that indicates active tuberculosis. These molecules still need to be tested under different conditions to see if they actually work when applied.

"The experience volunteers have - looking at lab test results, interpreting them, building theory off of them, etc. and exploring computational models through the interactive simulation - has really created a different kind of (complementary) expertise to professional scientists."

Game, gamification, separation

In my first post, I also introduced the different design approach reported by Sande Chen in her article. She described three ways of making citizen science games. One way is to design a game around a scientific problem. The gameplay is what helps solve the problem. Another way is to gamify the scientific problem. There is no real gameplay, but game elements have been added to the problem. A less common approach, so far, is the separation between gameplay and scientific problem. It seems that the first citizen science game designed around this third approach was Reverse The Odds.

This mobile game was a collaboration between Cancer Research UK and Channel 4. Player’s goal was to assist some colourful creatures, 'The Odds' , which population was declining. Players could play mini-games, upgrade and restore the Odds' land. To improve their lands and unlock the puzzle games, players had to earn potions. Potions regenerated with time, but could also be earned by entering the lab to examine cancer cell slides. This game, which goal was to help prescribe more accurate treatment for future patients, is now closed. Colin Macdonald, Head of All 4 Games, explains that the game was commissioned around a TV programme. They had managed to commission some updates after the programme ended. The funding then came to an end so after players worked through the last datasets, the game had to be taken down.

In Reverse the Odds, players could solve puzzles (left) to improve their land (middle). To upgrade the land, they needed potions that regenerated with time and that could be earned by analysis real cancer slides (right).

In Reverse the Odds, players could solve puzzles (left) to improve their land (middle). To upgrade the land, they needed potions that regenerated with time and that could be earned by analysis real cancer slides (right).

So where was I going with that?

Aaaand EVE Online!!

These citizen science games are free to play, and to my knowledge, none of them intended (is allowed?) to monetise. The development and maintenance costs depend on grants, funding, charity, donations. I don't think scientists count with a big marketing budget to promote their game and reach out new players. Keeping players engaged requires a well-designed core loop, motivational factors, but also time and energy for the development team (sometimes the same scientists doing the research). In most citizen science projects, games included, the participation follows the 90-9-1 rule where only a tiny percentage of players makes most of the contributions. Benjamin Keep explained:

"Really, if you took away just a handful of players, the project would be crippled."

Acquisition, engagement, retention issues are issues that Attila Szantner, passionate about games and citizen science, had noticed and decided to tackle. Him and his friend Bernard Revaz firmly believe that mainstream games can be a solution for some types of citizen science projects. They can harness players' skills and time to help solve real-world issues. They created Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS) to connect scientific research and games. They convinced CCP Games, EVE Online developers, to team up for the project and together they launched Project Discovery. In their pretty hard-core game, EVE players cooperatively help classify real scientific data. Using the same tools than biologists at the Human Protein Atlas, or astronomers at the University of Geneva, they contribute to science and accelerate biomedical and astronomical research projects. Project discovery is the first citizen science activity perfectly integrated in a well-established MMO. With millions of real scientific classifications, EVE Online players made of Project Discovery one of the most successful citizen science project. But I can't say too much now. The whole story will be explained in the next article!

Thanks to Benjamin, Jérôme, Colin, Karen and Attila who have always taken the time to answer to my questions for the last 2 years.

This post was first pusblished on my website, citizensciencegames.com. Twitter accounts: @Claire_csg and @CS__Games

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like