Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can you create a deep, story-based title that also functions as an exergame? DeAngelis looks at the history of exercise gaming and explains how his CMU university project Winds Of Orbis tries to twin the RPG and exercising for kids.

"...Descendant of Erdrick, listen to my words..."

~Dragon Warrior, 1989

For many gamers of the 8-bit generation, this opening line was an introduction to their first experience of the quintessential "hero on a quest" role-playing game (RPG).

For the next few weeks of the player's life, they would venture into dank, unlit dungeons and swamp-infested lands in search of treasure, a mythical Ball of Light, and the villainous Dragonlord.

Dragon Warrior completely immersed the player in a personal journey as they defeated hundreds of green slimes, upgraded magical weapons, and rescued a princess. Throughout all of this, the player witnessed their character physically growing in power.

As their avatar leveled up, many gamers would notice their virtual confidence rise in conjunction... but what did it do for their real world self-esteem?

When all was said and done and the mighty Dragonlord was defeated, the player would return to reality.

While their pixelated hero ran countless miles across countryside and engaged in hundreds of physical battles, the actual body of the gamer just spent dozens of hours doing thumb push-ups with their rear planted firmly to the couch.

Keep in mind that there's nothing wrong with a non-active video game; video games and physical relaxation generally go hand-in-hand.

But isn't it possible that there is an untapped market that would evolve the quest genre by combining it with active play? Could there be a reality that maps the player's actual limbs to the hero's virtual ones?

In the past twenty years, the percentage of overweight adolescents in the United States has more than doubled, resulting in nearly 30% of American children today being considered obese or overweight.

There are numerous reasons for this disturbing fact: an unhealthy diet, decreased interest in customary outdoor play, overuse of the Internet, and the proliferation of television programming. But the aforementioned factor of inactive video games is what our small team at Carnegie Mellon's Entertainment Technology Center (ETC) is striving to address.

There is an unfortunate correlation between the increase in child obesity and the popularity of video games. In 1999, the average child played video games for 29 minutes a day. According to the Entertainment Software Association (ESA), that number has more than doubled to approximately 63 minutes per day in 2007.

We understand that a problem exists, but what can be done about it? I won't bore you with a comprehensive history of exercise-based games (exergames), but products have been released since the eighties that merged movement and gaming like Nintendo's Power Pad. The majority of existing (and defunct) exergames are either sports-related or training simulators.

Despite the blockbuster success of a few products such as Dance Dance Revolution (see DDR champs in action), there seems to be a social stigma with most exergames that prevents them from being more fully embraced to transcend generations like such classics as Super Mario Bros., Legend of Zelda, and Final Fantasy.

Let's assume that DDR has defied this stigma, at least from a sales perspective. The core gameplay of the original game and its dozens of spin-offs is essentially "Simon Says" with vertically scrolling arrows. The player is limited by the very specific commands that the dance calls for: step left, right, forward, back, etc.

This simple gameplay works brilliantly for this type of game. After all, the player is learning how to move in rhythm with a pre-determined musical track, so the designers spell out an effective way for them to succeed.

This specific control provides feedback to the player, ultimately resulting in a letter grade for their performance. Still, underneath the surface, DDR simply uses a waterfall of arrow commands, limiting the possible choices and creativity of the player.

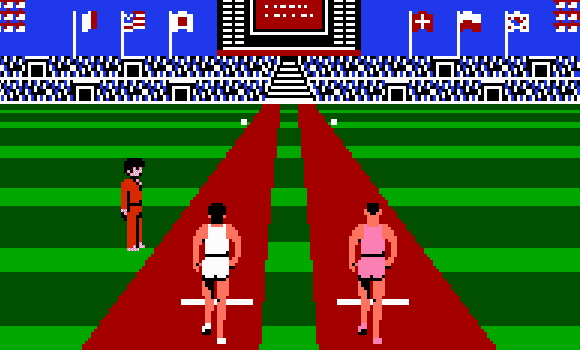

Nintendo's World Class Track Meet

Another pioneer of exergaming is Nintendo's World Class Track Meet Power Pad game. The player was confined to a straightforward track and could only move forward by running in place. This made sense for that type of game.

Why would anyone ever want to go backwards or turn in a 40 yard dash? All you have to do in a race is run (or jump, in the case of hurdles). These were extremely limited controls, but like DDR, it made sense for the context of the game.

With these two examples in mind, what if it was possible to move beyond the restrictions that have been assumed by existing exergames? What if a game was built in the vein of a Zelda or Dungeons & Dragons epic with free navigability and exploration? Could we take inspiration from the action-adventure genre to create an active-adventure? This is exactly what our team is trying to do.

The seven members of our team come from diverse backgrounds, but we all agree on one thing: we love the experience action-adventure video games can provide. While we all grew up playing different games, we took our disparate perspectives and agreed that there has never been an exergame that molded traditional elements of adventure gaming with active "exercise-based" inputs.

According to the ESA, over 40% of game sales are accounted for by action, adventure, and RPG-style games. Furthermore, many RPG fans are in dire need of additional activity of some sort, as the very nature of RPGs consists of countless hours of sitting still.

This goes to show that there are plenty of non-sports gamers longing to escape to fantasy worlds, so why has the action-adventure/RPG genre been neglected when it comes to exergames?

While there are always exceptions, it can be argued that many D&D adventurers dislike traditional organized sports and exercise. Perhaps this market has seemingly been ignored because there aren't any exergames that have been tailored to their tastes.

The stereotype of the lethargic adventurer sitting in a computer chair exists, but what if these gamers had a product to choose that would allow them to play with all the components they love in a game -- just in an active manner?

The success of the Nintendo Wii led us to believe that a game could be created that would successfully answer this question. The Wii remote allows a player to move their arm to swing a sword without pressing a button as in No More Heroes or Zelda, potentially simulating upper-body exercise.

Encouraging full upper-body range was a nice idea, but we wanted to differentiate ourselves further. After all, Wii owners now realize that they don't have to swing their entire arm to return a tennis volley in Wii Sports or finish off a foe in the Wii version of Dragon Quest Swords; a simple wrist flick will do, hardly replicating significant activity.

In a meeting with medical experts at University of Pittsburgh's Medical Center, they recommended designing a way to increase a child's heart rate when playing, as this would exponentially increase the possibility of a meaningful workout.

We immediately thought of the success of the DDR dance pad. After extensive research, we couldn't find any other game that re-designed the dance pad to be used for a non-dancing/simulation game.

On the one hand, we were excited to try something entirely fresh: combining the Wii remote and floor pad to work as one user interface for an action-adventure. On the other hand, we were a bit concerned that this combination had not already been accomplished by a professional developer.

Was there something we were missing? Would it feel completely unintuitive to combine the two peripherals? We didn't know until we finished our initial prototype, but we were excited by the possibilities in front of us. We had two astronomically successful devices that were proven successes in millions of homes; why couldn't we make them work as one?

With the foot input established and re-purposed, the floodgates opened with ideas as we were able to literally place the child in a video game hero's shoes.

To make our hero jump over a chasm while being chased by a menacing enemy, the player will jump in their living room; when our hero unleashes a three-step melee combo on an antagonist, the player will not only swing their arms with the Wii remote, but move their feet in conjunction to mimic the attack of their avatar.

The child will be actively engaged in a traditional action-adventure experience, but their mind will be focused in the flow of the gameplay and aesthetic beauty of the world, not on burning calories.

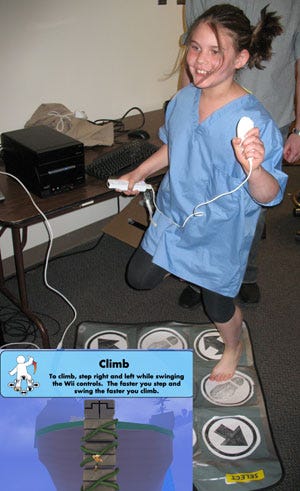

After finishing our first complete tutorial and world, we believe this can be done, and we're working to prove it with our currently PC-based project (pictured above), The Winds of Orbis: An Active-Adventure.

While we are seven graduate students and not currently professional developers, we have been operating like any small development house would. We have two programmers, four artists (concept artist, animator, character modeler, and environmental artist), and a producer/composer.

Every team member's voice is heard and has contributed to the overall design of the project starting with a month of pre-production followed by almost three months of production. We have functioned efficiently, using a loose version of Scrum to keep focus and hold each other accountable for individual tasks.

We knew we could be in trouble if we tried to incorporate too many gameplay modes instead of focusing our attention on one or two effective and engaging mechanics. Following the advice of faculty at the ETC, we placed ourselves in a combat design vacuum for a month, since this is such a critical mechanic in the game.

Through routine playtests with hundreds of tissue testers -- meaning we never used repeat testers -- we iterated to make sure the battles felt exciting, yet comfortable and intuitive.

Designing an action-adventure game around an entirely new user interface was a challenge.

Designing an action-adventure game around an entirely new user interface was a challenge.

We knew we had to differentiate our floor pad from DDR, so we designed the pad in an ergonomic way, with offensive attacks and defensive movements clearly delineated.

With this in mind, we brainstormed and paper-prototyped until the combination of the Wii remote, nunchuk, and floor pad were intrinsic and additive to the experience rather than unintuitive tacked-on gimmicks.

The abovementioned punch is an example of this. We combated the "wrist-flicking" tendencies of other Wii games by animating our hero to literally step forward into his punches.

By mapping the hero's digital limbs to the player's real ones, this allowed us to design a reason to avoid the dreaded wrist-flick; the child is stepping because the protagonist steps to throw an attack.

Different attacks can be initiated depending on where the child steps and which hand they swing (the nunchuk is also used to fight if the player desires, allowing true two-handed combat).

Another example of our plan to merge a traditional action-adventure with exergaming is using dodging during combat to increase cardiovascular activity.

The nature of Orbis' main character allows him to be very agile, so we thought this could be a great opportunity to open up combat beyond a stationary duel. When engaged in battle with an enemy, the child can move their feet to the left or right by hopping to the correct inputs.

This naturally causes their shoulders and body position to shift as their avatar mimics their dodge in real-time, avoiding any threatening attacks from an adversary.

This adds depth and strategy to the combat, as the player can circle-strafe behind an enemy to throw an attack, simulating an extremely active "stick-and-move" style of gameplay. No more pressing a shoulder button or choosing "Defend" from a menu while you absorb a blow... Now those little slimes from Dragon Warrior will have to deal with a mobile hero.

While our focus was primarily on honing the combat, we budgeted additional time to add other features such as throwing physical objects, super-sprinting (or bull-rushing), and climbing walls, an exercise the children playtesters seemed to really love.

Who would've thought we could tell a kid to rapidly mimic climbing in place and have them happily oblige as their character bounded up a 100 foot wall?

Regarding sprinting, we were unsure if the children would want to physically run in place. After all, any child who is ordered to sprint in place by their sports coach isn't a happy camper.

Because we did include traditional analog movement, what if they simply relied on that non-active control scheme to travel and explore, without moving their actual body at all? Through strong visual feedback and cleverly designed segments, we found that the testers would run given the opportunity.

As soon as they saw their cat-like avatar go from an upright jog to an outright sprint on all fours that could break through walls, the visual payoff encouraged them to choose the running option over the analog walk.

Choosing is the critical choice here; if we instructed the player to jog everywhere and took away conventional control, we would have risked alienating our target market by forcing them to do something they wouldn't inherently choose or get tired from quickly.

But by giving them an option, we accomplished a few things: the game seems more user-friendly by maintaining a time-honored control scheme, and it empowers the child to make creative decisions at their discretion.

Once our mechanics were in place, we knew it would be important to provide some responsive feedback to encourage the kids to play continuously. For example, when the child punches a block out of their path, the physics allow the block to forcefully fly away.

In addition, vibrant visual effects and exciting sound feedback assist in making the child feel powerful when they swing their actual arm with the hero.

We've heard some concern from advisors that this idea may dissuade children from going outside at all. As with mature-themed games, it is ultimately up to the parents to monitor the gaming habits of their children.

We do know that adults and parents who have seen our demo have communicated how excited they would be to see their children playing games like Orbis, as opposed to playing inactively all the time.

With this said, our goal is not to supplant traditional outdoor exercise, play, and sports activities. Rather, we are aiming to replace the sedentary 30 to 60 minutes a day that the average child spends using their thumb while sitting on the couch with an experience that will encourage them to stand up, move, and sweat while playing the type of game they love with a smile on their face.

To affect this meaningful change in a game, and hopefully within the industry as well, we believe the key is giving kids what they love... adventures that empower them to be active.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like