Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

An excerpt from '21 Unexpected Games to Love For The Atari VCS,' Atari Video Cube doesn't actually work like a real Rubik's Cube. It's a lot more accessible! It's a laid-back kind of puzzle game that Atari originally sold by mail order.

[This is an excerpt from '21 Unexpected Games to Love For The Atari VCS', available in the current game eBook Storybundle, which covers a number of classic VCS games that, untethered from nostalgia, may still be of interest to a player who didn't grow up with the system. The Atari Video Cube is a laid back kind of puzzle game that's not nearly as imposing as an actual Rubik's Cube. It was developed before the Game Crash of 1983, but sold through mail order until Atari revived the VCS/2600 to try to compete with the NES.]

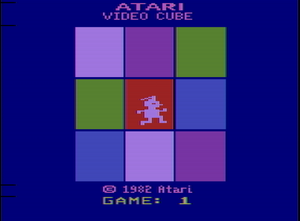

Atari Video Cube

1 player, joystick. 4K in size.

Created by an unknown developer working for GCC. Published via mail order in 1982 by Atari.

Accessibility: 4/5

In a sentence: It's not a Rubik's Cube, but instead you swap individual colored squares on the cube with the one you're carrying and try to get each side all the same hue in this laid-back puzzle game.

Squares In The Mail

In the 80s it seemed like anything could become a fad. You think fidget spinners were big? One of the best-selling toys of the decade was a super-hard puzzle� that very few people could complete. Rubik's Cube was popular enough that it remains well-known today in a way that Cabbage Patch Kids and Beanie Babies are not, partly because it continues to be sold in various formats and sizes, and partly because there's still a bit of magic about it. Twisting one around in your hands, it's difficult to conceive how such a thing could even be invented, let alone assembled into a thing you can own for about $12.

Atari was a fad of comparable size right around the same time, so combining the two must have seemed like a paring as salutary as sparkly balls and disco. Atari had a coder from GCC, whose name does not come down to us, work on this interesting puzzle game that despite the name and appearances is actually not a Rubik's Cube. It's a great deal easier, and because of it, rather more fun.

Perhaps sensing legal trouble if it appeared on then-Cube-licensee Ideal's radar, it was not sold at first on store shelves, but instead as a mail order-only product offered in Atari's newsletter. When the VCS got its shadowy second life as a distant competitor to the Nintendo Entertainment System, some units appeared in shops at that point, possibly unsold inventory. atariprotos.com says that it was sold with Rubik's Cube branding at this time, but I don't remember seeing it myself. I presume they are accurate.

The Game

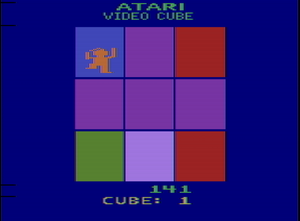

It's quite simple. You have a person, like an elf or an imp and identified by the manual as "Hubie the Cube Master," who lives on a cube, each face divided into a 3x3 grid, like a Rubik's Cube. And like a Rubik's Cube, each face's sub-squares are colored, and also like a Rubik's Cube, the colors are scrambled at the start of play, scrambled around the cube. There's nine of each colored square; your job, like the puzzle, is to get it so that each side of the cube is a single color.

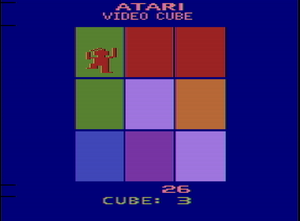

How you do this is how the game diverges from Ernő Rubik's portable conundrum. Your cube-living gremlin moves between the squares of the cube according to how you press the joystick. You only see one side of the cube, the one the elf is on, at a time. When you move them off the side of the cube, it "rotates," with a simple 3D effect, to show the next side. Your imp-person has free reign of the cube with one exception; they can change color through the game, but can never stand on a square that matches the color they currently are. You see, they're shown in relief against the background of the cube color they're standing on. If they were standing on a spot of the same color, they'd be invisible, and we can't have that!

How do you change color, then? You can "pick up" the color on a spot when you press the button. Then the imp changes to that color, and the color they previously were is dropped and becomes the color of that square. Then you can move to another space, exchange colors there, and so on, always with the limitation that you can't cross onto a space that's your current color.

Slowly, space by space, you construct a "solved" cube in this way. It might sound easy, since at any time five kinds of spaces are walkable out of six, but as you solve spaces you start having to plan your moves a bit. Remember, solving a side requires filling it with the same color, you have to be that color in order to drop more of it into that side, and a side is hidden from your view until you walk into it. The result is that a kind of hidden wall of that color develops as you fill that side with more of the color you want it to have. The effect is even more confounding because of a clever little fact about the cube, that shows its unknown creator's attention to detail....

Your task is made a little harder, and a little weirder, because of the geometry of cubic shapes. Think about if you had a cube in front of you. Of course, the Atari can only show it orthogonally, its sides parallel to the screen. Now take this cube, imagined in your mind's eye, and rotate it so the side on its top is now facing you. This means the original side that was facing you, we'll call it Side One, is facing the floor. This is just how the game does it, with a nifty 3D effect.

Now, turn it left, so the currently-viewed side is on the left. Side One is still on the bottom in this example, but it's been rotated 90 degrees. Now, if you turned the cube "up," to bring Side One back into view, it'll be rotated 90 degrees counter-clockwise from your original view of it! My point is, the Atari Video Cube obeys this rule; it's not like a six-screen flat grid you can scroll around, your perspective on the squares can become rotated based on how you scroll them around.

Imagine if you were playing the game, and your elf-friend was tying to fill Side One with blue squares. You might see that the upper-left space on that side is the only one left to fill, so you leave the blue side looking for a new square. It could be anywhere. When you find it, unless you retrace your steps to get back to the blue side the same way you went away from it, that one space might not be on the top-left; it might be one of the other corners. If you haven't paid attention to how you rotated the cube, you might have to pace around, trying each of the other corners, until you find the one that allows you entrance.

This may sound confusing, but it's not that hard to get used to really. It's nowhere near as difficult as an actual Rubik's Cube, and the real point of it all is to work on optimizing your solutions. 50 puzzles are included on the cartridge, and you can play each either for lowest moves or fastest time. Note that they're not selected by the Game Select switch, but by the joystick before the Reset switch is pressed. There are the usual number of game variations, which include modes that have the computer showing you an optimal solution to a cube, modes that "black out" the colors so that they're only visible when turning the cube, and perhaps the most interesting, a mode that restricts movement to up or right, which requires different strategy to solving.

It's a shame that the Video Cube didn't make it to store shelves back in the glory days of the console, as it's one of the most interesting cartridges available for the VCS. It's interesting for being quite a "pure" game. There are no enemies, extra rules or needless complications. You're free to keep playing until you solve a puzzle, and the only barrier to that is that of the colors posing obstacles, which is both more of a problem than you'd think, and still not so harsh that you'll be stuck for long. It's a nice unwinding kind of puzzle, something to flip around for a few minutes.

It's a shame that the Video Cube didn't make it to store shelves back in the glory days of the console, as it's one of the most interesting cartridges available for the VCS. It's interesting for being quite a "pure" game. There are no enemies, extra rules or needless complications. You're free to keep playing until you solve a puzzle, and the only barrier to that is that of the colors posing obstacles, which is both more of a problem than you'd think, and still not so harsh that you'll be stuck for long. It's a nice unwinding kind of puzzle, something to flip around for a few minutes.

And that's about all there is to say about Atari Video Cube. Sometimes, simple is best!

Notes

The source for the GCC credit on Atari Video Cube is atariprotos.com. That site also notes that Atari had in development a more accurate version of Rubik's Cube, presented in perspective. From a technical standpoint it's interesting, but it's just not as interesting a game as Atari Video Cube.

Links

Also try...

Of course, Q*bert!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like