'Roguelikes are about many truths, about a pluralistic view of the world,” says Short. 'There's not a single truth of what the game is, and what the intended experience is.'

From Rogue to FTL, developers have long used procedural generation to create unique environments and opponents for players. But can designers also use it to create unique narrative twists?

In listening to how different players talked about their Roguelike experiences, Tanya Short saw an opportunity to use procedural generation to build “personal player narratives.” The goal of creating such narratives is a central design pillar with the upcoming game Moon Hunters, on which she is lead designer.

The game is a co-operative RPG that tasks players with finding out what happened to the moon, which has gone missing. Against the backdrop of fantasy version of ancient Mesopotamia, players explore a world in which environment is randomized, but so are the story beats and characters they encounter along the way. Across short play sessions, players retell the same myth with different characters the way that a storyteller might continually recast Pandora, The Monkey King, or other ancient heroes. It's a tradition dating back across many cultures, including Polynesian storytelling and classical myth making.

In searching for an opportunity to have players experience “the multiple truths of storytelling,” Short hit upon 3 fundamental lessons for investing players in a randomized quest.

1) Break away from duality

"Roguelikes are about many truths, about a pluralistic view of the world. There's not a single truth of what the game is, and what the intended experience is."

To start, Short explains that nailing the “multiple playthroughs, multiple stories” tone for Moon Hunters depended on successfully introducing what it means for a story to have different retellings. To her, those carrying versions ultimately represent a wide variety of possible truths, with each tale's telling having a different moral or point depending on the context of when it was told.

Because of this, Short says traditional moral duality systems wouldn’t work as well as it would in a more tightly scripted game. “I think it fits thematically, with Roguelikes being about many truths and being a pluralistic view of the world,” says Short, “and not a single truth of what the game is, and what the intended experience is.”

But duality systems aren’t just about player choice; they're also a means of tracking progress. Short drew inspiration from Ultima’s virtue system and created assignable traits to help players track their decisions in a given runthrough to help define who their character is through a given adventure.

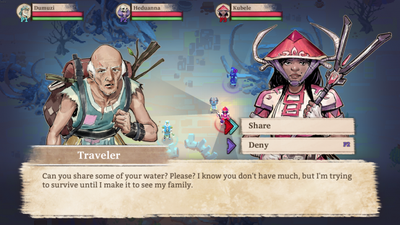

To keep these traits interesting, Short and her team had to constantly hone dialogue choices to drive changes in the player’s core stats. Here, she says that eliminating duality created a huge challenge for maintaining player interest in dialogue trees. “One of the things we struggled through in Moon Hunters is player agency versus interesting outcomes. In any given dialogue, you’re limited to 2 choices, and in some cases, for both choices to be interesting, they have to be really weird.”

To keep these traits interesting, Short and her team had to constantly hone dialogue choices to drive changes in the player’s core stats. Here, she says that eliminating duality created a huge challenge for maintaining player interest in dialogue trees. “One of the things we struggled through in Moon Hunters is player agency versus interesting outcomes. In any given dialogue, you’re limited to 2 choices, and in some cases, for both choices to be interesting, they have to be really weird.”

“For instance, if you encounter somebody praying, you traditionally might either interrupt them or walk away. Walking away is a little boring, so we wrote in things like ‘singing’ or ‘dancing’ to show you more about your character.”

2) Make room for mundane moments...but make them compelling

Roguelikes, with the rare exception, don’t have much need for “the mundane.” FTL might use an empty space sector as a breathing point for a beleaguered player, but challenge-driven roguelikes don’t benefit from much downtime.

For narrative procedural content, Short says that mundane moments matter as much as the epic ones. “If you look at The Epic of Gilgamesh, you remember that this story came from someone probably named Gilgamesh who was kind of violent and a hero, but what we hear are exaggerations of his deeds.”

“But it’s interesting to think about those parts where you imagine the real Gilgamesh being asleep in the forest for a few nights, and maybe he was afraid for his life. What did he say to his friends? You create these natural moments people have when they go ‘well we’ll tell a better story about that later.”

“But it’s interesting to think about those parts where you imagine the real Gilgamesh being asleep in the forest for a few nights, and maybe he was afraid for his life. What did he say to his friends? You create these natural moments people have when they go ‘well we’ll tell a better story about that later.”

Moon Hunters mostly builds this mundanity in its campfire system, which Short says evolved from a tribe-building system promised in their Kickstarter video. Tribe-building, Short realized, wasn’t very “heroic” in the same way other parts of their game were, and they shifted resources to have the player’s small actions around the campfire reflect what most players do when they level up and assign skill points---reflect on where they have gone, where they’ve been, and what they need to do.

3) Manage scope differently

Having worked on Funcom projects like Age of Conan and The Secret World, Short’s background around quest layout typically dictates working with extensive dialogue trees built around a handful of core characters. But for procedural games, Short advocates creating many small questlines out of a large cast of characters.

“It's more like you make 3 dozen characters, put them out there, and once they have little personalities, interactions and knowledge about the world, you interact and understand their perspective,” “says Short. “Then [the player] has the tools to say ‘who do I hope to see again based on what we did?"

It’s an argument for breadth over depth, but it’s a method that helps players assemble wildly different playthroughs based on their choices. Short points out that this is part of the strength of Sunless Sea, “They have 200 interactions, and there aren't a whole lot that have multiple layers. So seeing different branches is really interesting because the core of the tree is really interesting.”

Ultimately, the most visible effect of this strategy- is that Moon Hunters is able to generate interesting encounters that have narrative relevance whether they happen at the beginning, the middle, or the end of a given player’s run.

It’s the kind of thinking Short hopes shows the strength of what procedurally generated games can do---and may help you out the next time you attempt to create randomized content.

For more tips from Tanya Short and Tarn Adams on Procedural Design, be sure to check out their upcoming talk at GDC 2016.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like