“You have to dial everything up to 11 in terms of feedback,” said CCP's Andrew Willans today in a talk about VR game design lessons learned during EVE: Valkyrie's development. Also: Text sucks in VR.

Andrew Willans has been in the game industry for a while, working on projects like Watch Dogs and Grow Home before joining CCP Games to work on Eve: Valkyrie.

Today he popped up in San Francisco to deliver a postmortem of the game at VRDC, full of lessons learned from launching the game on Oculus Rift, PSVR and (soon) the HTC Vive.

Willans joined after Valkyrie was prototyped, but before full-on production started, so devs who are looking for less talk of VR prototyping and more insight into how to take a VR prototype to a full released game may appreciate what he shared.

Willans compares VR game design to amusement park ride design: you want to create “end-to-end fantasy.” As an example, he points to the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland, where right from the moment riders enter the line they’re drawn into an alternate reality by the architecture, set design, attendant costumes, and the like.

“When I started we were about 28 people, and we’ve never exceeded 40,” says Willans. That (relatively) small size limited the scope of Valkyrie, but also ensured the team would be quick to adapt to new learnings or challenges. A top learning was that the size and scale of your VR game dictates how well it can convey things like the feeling of being in a speeding starfighter.

“Fast flight simply diminishes the sense of scale,” says Barballo, explaining why designers wound up scaling up everything in Valkyrie to 1.5 times player scale. “We made everything bigger, and made that sense last for longer.”

They also decided to add in small “speed particles”, little bits of space debris that fly past players but have no meaningful in-game effect -- their collision is limited to bouncing off a player’s windshield.

But the little things weren't a big part of Willans' talk. He spent a lot of time exhorting fellow VR devs to think bigger, sharing the example of a Valkyrie mission that was meant to end with a huge big carrier jumping in and firing a giant laser at its target, creating a huge impressive explosion. In testing, players kept missing it because even though it was massive, they could conceivably be looking away when it jumped in -- as big as it was, in VR the carrier just wasn't big enough to guarantee player attention.

“An important thing that we learned about VR: you have to dial everything up to 11 in terms of feedback,” Willans said, “You’ve got to build these things and you’ve just got to try them. That’s the beauty of having a dev team that is quite small: we could have daily feedback meetings after playtest sessions.”

(Later, Willans noted that the Valkyrie team has mandatory playtest sessions at least 3/week -- if there are empty chairs in the playtest, they'll go out and hustle people into taking part, because they think it's critical.)

He also took pains to remind fellow game devs about the value of creating (and sticking to) an blueprint of what, exactly, you want your game to be. For Valkyrie, a guiding principle was that the player is a space pirate “These high-level statements kind of help reinforce, and can help you sanity-check your features down the line,” says Willan.

Of course, that doesn't mean you shouldn't stray away from your initial design plan -- just that you should be sure the course of development always matches up with your high-level goals for the project.

For example, the Valkyrie team struggled to make a single-player campaign -- they repeatedly said the game was meant to be multiplayer, but fans kept asking for single-player stuff. Willans says they tried to walk the middle path by adapting the mulitplayer missions for single-player play, layering in a bit of extra narrative and extra mechanics like wave-based AI enemy attacks.

What they wanted to do, but ultimately left on the cutting room floor, were asynchronous multiplayer VR flight challenges. The idea was to pit players against the recorded performances of their friends in various challenge courses, an idea that was ultimately scrapped because the team ran out of time.

“We may return to that at some point, the prototypes were a lot of fun,” says Willan, noting that some of that cut content was re-used to build out things like the game’s tutorials.

And early on, Valkyrie was significantly more "grindy" -- Willan says it could take hours for a player to unlock key features of the game.

“Something we discovered during our alpha period...it just felt like too much of a grind to get to the real tools,” says Willan. “It’s a really strong lesson, one I especially learned on Grow Home, is that if your game has a lot of cool stuff, just let people have it and play with it.”

The same focus on approachability can be applied, in a sense, to VR game UI. Willans recalled how, in the course of Valkyrie’s development, some of the game’s were displayed as static text hovering in front of the player. That was greatly improved when the team hit upon the idea of having things not just float in front of the player, but actually project out from them -- as though they were interacting with real, futuristic tech in the world.

“It helped create the fantasy that my avatar was just sitting on a crate, chliing, waiting for a battle,” says Willans, referring to an interface players see when they aren’t actually in a ship. “Chiling out looking at the equivalent of a mobile phone, like we all do.”

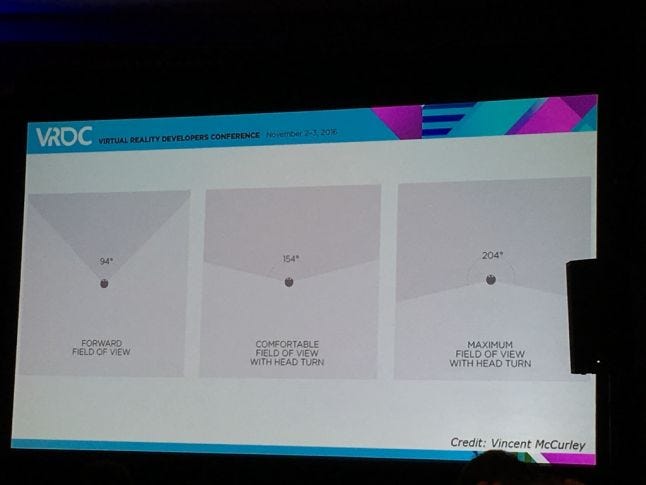

They also came to really respect the comfortable fields of view for players, and comfortable viewing distances (see images below.) In short, you typically want most of what players are looking at to be within 10 meters of them (but farther than half a meter away) and within about 94 degrees of their eyeline.

Two images illustrating comfortable field/depth of player view captured during Willans' talk, which he attributes to VR filmmaker Vincent McCurley

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The Valkyrie team ran into trouble trying to squash something as simple as a level select screen into this comfortable viewing range, since they had more levels than could easily fit within the sweet spot.

“Our UI at the minute is a compromise; it’s a happy middle ground” says Willans. “We ended up having this rotating wheel where we place the planets, the levels, to be selected, at an optimum distance, within the vision cone.”

The team made a similar compromise on the ship select interface, one that sought to strike a balance between “dialing it up to 11” and making ship models look big and impressive, while also keeping them comfortably readable.

All of this comes down to a fundamental truth of game design right now: most game developers envision games on a 2D screen, rather than a 3D immersive space. It’s a hard habit to ditch, says Willans, but you absolutely have to -- and remind everyone on your team to think in 3D.

“2D thinking: it’s hard to break,” says Willans. “It’s a running joke around the office. We say ‘have you checked it? Have you checked it in the Rift? Have you checked it in PSVR?’”

In closing, Willans distilled his VR dev learnings down to a simple aphorism: “Dial it up to 11, then tune back.”

"You want to “create those ‘wow’ moments, then scale it back for approachability and comfort. It’s much easier to scale down than up,” he says. But also, don’t forget to have something great for the player to do after the initial “VR buzz” has worn off -- because it will wear off.

Oh, and also: “Text looks rubbish. Seriously,” adds Willans. ”I’m not a fan of text in VR.”

Read more about:

2016About the Author(s)

You May Also Like