What information should you tell the player, and what will shatter their immersion? We investigate.

March 10, 2015

One inherent tension in any remotely story driven game is the pull between what you show to the player so that they can actually play the game, and what you keep back in an attempt to foster a more convincing suspension of disbelief. Every HUD element, each abstract concept communicated by a numerical value, each option that the player takes; all of them are reminders that youare playing a simulation that's predestined, considered, and limited. So the question arises of what exactly you show to the player, when you have all the information available to you as a developer. What is too little, and what is too much?

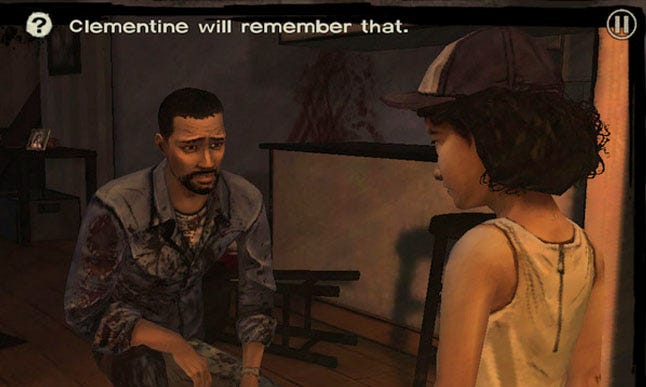

Telltale catapulted games of pure narrative into the commercial stratosphere with The Walking Dead Season One. Emerging out of adventure games into something that was closer to interactive fiction, it did an impressive job of weaving a strong branching narrative that wasn't compromised by the constraints of a small team and a small budget. But the novel ground it was breaking gave rise to one small notification that came very close to ruining the game for me. "Clementine will remember that" loomed large, not so much in what it told me, but what its absence did.

"I hated it, and got into a big brouhaha over it." Sean Vanaman, writer and lead on The Walking Dead Season One, outright groans when I bring that notification up, before reframing things. "You have to remember that Telltale had never made a game where your save file mattered, so that was the big point. People [at Telltale] were worried that there were six to eight weeks between episodes, so people might not remember that their save file mattered. The decision was made that we really had to hit them over the head with a frying pan so that they knew that the decisions they were making were remembered. I didn't agree with that, because I thought it would produce the feeling that, any time that notification doesn't come up, people were going to know that ‘Oh, I'm on a linear path, nothing has changed.'"

The irony of it is that even in those times where I wasn't notified, The Walking Dead was remembering what I was doing. Everything was collated, each data point noted and saved. My frustration isn't the only reaction to that notification, however, nor even the majority.

"That [notification was] such an elegant solution to a complex problem that's been around for so long." Jon Ingold, founder of 80 Days studio Inkle, told me. "When I make a choice in a game I usually assume the game isn't paying attention, but when I see that I go 'Oh! It is!'"

I would contend the elegance of it, though, when both The Walking Dead and 80 Days both do an excellent job of solving that problem intelligently, through well considered and placed call-backs to decisions that you've made.

"The drawback when it comes to call-backs though is that you don't know until that call-back happens that it has been paying attention," Ingold explains. "If you want to prove to players that youare paying attention you have to do it really really fast. The way we did that is with the map. It proves to you that your choices do matter, as you can see which way you're going."

"If you want to prove to players that you're paying attention you have to do it really really fast."

The problem that all of this is concerning is the idea of a narrative possibility space. Many games that have a strong focus on narrativeyare exercises in creating a story that feels as interactive as possible, but are also trying to herd you, unawares, down a very specific path. Every choice you make diverges, until you're ushered back towards the common finale, perhaps with a few varied permutations. It's a restraint brought about by limited funds, and limited time. You can only flesh out so much freedom before you hit a wall.

The difficulty is in masking that from the player, to make them go in willing to suspend their disbelief, and not then clumsily shattering it with the wrong piece of information. The more ambitious you make the freedom you promise, the more likely you are to break that suspension. Skyrim claims a world of complete freedom, but the instant you embark on a quest that should have wider implications and none occur, you realize that that freedom is only skin deep. Mass Effect tasks you with saving the universe your way, except they're all the same way really, with mild cosmetic differences.

"You never really know whether exposing the possibility space of what could or couldn't happen or keeping that stuff hidden is going to take the player out of it," Vanaman offers. "You just can't know, so much of it is gut. Had I been a dictator on The Walking Dead I probably would have erred on showing too little, and I think that would have been a detriment on the mass appeal of the game."

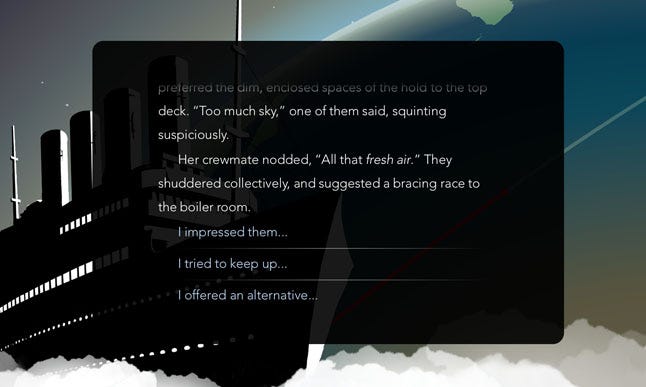

However, there are ways you can mitigate the chances of taking the player out of it. In 80 Days different choices occur in the text based on your previous choices, or the items in your luggage, or the places you've been to. The trick is how that information is obfuscated. Meg Jayanth, writer of 80 Days, explains it: "There are actually quite a lot of dialog options in the game that are based on particular modifiers, like if youare a particularly good valet, or a particularly well dressed one, but we don't have a symbol beside them that tells you ‘This is your skillful option.'"

The closest they come to pulling back the curtain is the occasional announcement at the end of a chunk of story that your character has changed, gaining a trait like "suave" or "zesty," interpolated adjectives that describe the combination of three primary traits that are numerically tracked depending on the decisions you make.

"The reason we added it is that there are a lot of choices in the text about the kind of person you are and want to be," Ingold elaborates. "90 percent of the time the player is making that choice because it's an interesting choice to make, but just having a little thing at the bottom that tells the player that weare paying some attention is just enough to make it feel significant."

"If you have a morality system just based on +3 nice points, it sort of undermines you from the start. It encourages the player to min-max."

This gets back to that tension. You don't want a player to feel ignored, but you also don't want to smother them. Perhaps it's the lineage of CRPGs where everything is rendered as a numerical value or a concrete trait, but the tendency towards reducing complex concepts into a simple number is one of the worst offenders when it comes to pulling a player out of a story.

"A hell of a lot of games get away with doing a hell of a lot of things just by using abstract numbers," Ingold continues. "If you have a morality system just based on +3 nice points, it sort of undermines you from the start. It encourages the player to min-max."

When it comes to selling a player on the story, this can be a crucial mistake. Framing a choice in terms of success in the game rather than narrative impact, means that it isn't a narrative choice but a mechanical one. The primary objective in highlighting these things is to have conventions of story-telling in games questioned, especially those that have carried over from the mechanical side.

Incentivizing abstract concepts has that same effect of "gamifying" your story. One can argue that BioShock's central moral choice of whether to harvest or save the Little Sisters is rendered moot by removing the material advantage of harvesting. You actually end up with more Adam and more supplies by saving them, which means that the right path is also the most self-serving. It's no longer a moral choice, but a mechanical one. Youare playing the game, not being part of the story.

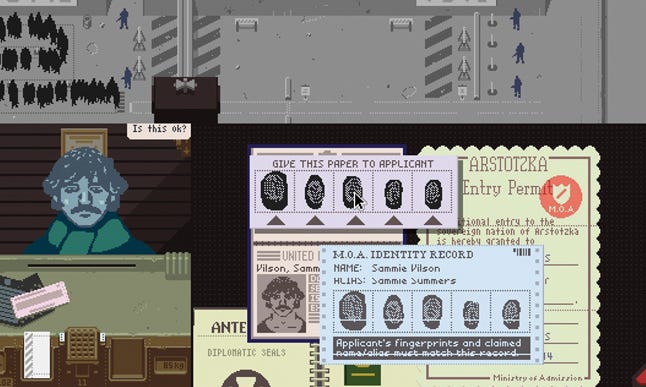

One excellent example of the opposite is Lucas Pope's Papers, Please, a game wholly concerned with the paranoia and suspicion of being a border agent for a totalitarian regime. Ambiguity is central to it being effective, and something Pope spent a lot of time cultivating.

"'Not knowing' permeates the entire game -- I think it's the key element of border inspection," Pope tells me. "You make choices on very little information, and often don't even see the results of your decisions. The person you just approved or denied walks out of your booth and you have no idea what happens to them. I wanted to take that low-level nebulous uncertainty and extend it to every aspect of the story. You have so little information about everything that almost nothing is ever certain. Even the sympathetic sob-story immigrants could just as easily be conning you."

"The level of ambiguity, unfilled blanks, and not-knowing-ness really gave me a lot of freedom to do a lot with very little. "

What makes this ambiguity work isn't unique to Papers, Please. It's a version of the old adage to show, don't tell, giving players the room to imagine and speculate rather than confirming either way. You can essentially have your cake and eat it, as long as you don't frustrate the player by withholding information they expect to know, narratively.

And that isn't the only benefit of withholding information from the player. Pope explains: "The level of ambiguity, unfilled blanks, and not-knowing-ness really gave me a lot of freedom to do a lot with very little. Immigrants don't say much, the neighboring countries' backstories are never given, there's no detailed tutorial, characters' fates aren't revealed, rules aren't explained clearly, etc. I intentionally tried to create a world that required the player to fill in most of the blanks themselves. Moving things into the player's head like that helped in all sorts of ways, with imagining the outcomes to their decisions being one of the major benefits."

This is something that both The Walking Dead and 80 Days both benefited from, too, with the travel theme forcing the player to leave behind locations and characters before they can truly see the impact of their decisions, instead moving forward with that decision informing their behavior and the way their traveling companions treated them.

Designers on all three games also made very conscious decisions about which information the player is constantly aware of through the UI. The Walking Dead had an extremely minimal and contextual HUD, so that it often looked more than a cinematic than something you were in control of. 80 Days, too, keeps things on the minimal side, keeping you aware of your funds, Fogg's health and the time, both of day and how many days into your 80-day trip you were. Papers, Please took it even further, with every bit of information while in the booth being an actual tool of some kind, whether it's your rule book or the stamp that you use to accept or deny immigrants entry.

In Sean Vanaman's upcoming game with his new studio, Firewatch, UI is something they have needed to spend a lot of time considering. "Everything in the UI is very concrete and very real because so much of the story in the game and your relationship with Delilah is not concrete and is difficult to understand. The information we put in front of you is very simple and solid. I don't want you to have to worry about what it means."

"Interactive fiction is a magic trick, and it's always been a magic trick."

Every game is trying to evoke something, even the most mechanical and abstract, but when what you're trying to evoke is a sense of being part of a story, or part of a world, it's incredibly easy to have the entire thing come crashing down with one small piece of information that was superfluous and one reminder too many that this is a simulation, and not a game. By allowing the player the possibility to question what is possible and what is not, and never giving them confirmation one way or the other, you avoid the risk of creating negative space, of limiting that possibility. Encouraging confirmation bias is one way to do it, and keeping the player in the dark about the inner workings is another.

"Do your items and qualities matter?" Ingold poses a rhetorical question. "Sometimes they do and sometimes they don't. Do we tell you that? Of course not. We make it up as we go to fit the story. It depends how we felt at the time, but that's ok, because it supports the story. So long as it's always doing something interesting.

"Interactive fiction is a magic trick, and it's always been a magic trick. It's sleight of hand to try and convince you that this pre-programmed robot that we built three months ago is actually telling a story that's changing for you right now. That's the goal, to make it come to life."

You May Also Like