We talk to Blendo Games' Brendon Chung about Quadrilateral Cowboy, his love letter to a 1980s style vision of hacking complete with chunky old tech and staticky, tactile virtual space.

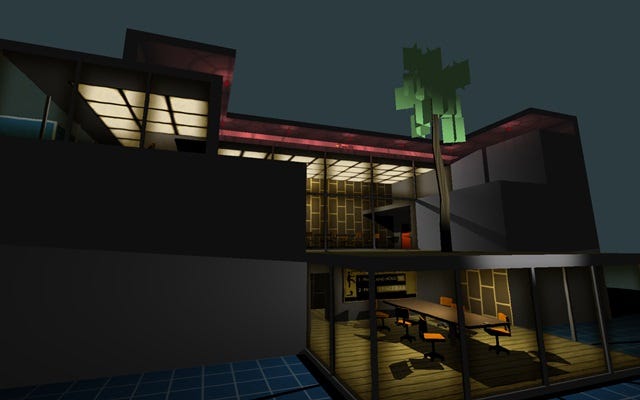

As my build of Quadrilateral Cowboy opens, I'm riding a speedbike along a train track, listening to my little portable Vinylman. I'm aware the soft strains of Clair de Lune are a homage to the heist films in which it commonly appears, but I can't help but find it soothing as a wave when I mount the train, socket into the door's controls and make it slide open with a hiss. A banner waves gently off the end of the train car: HAPPY NEW YEAR 1980. The cube-shaped shadow of my head falls gently across the interior. Later, when the crew and I are at our sparse headquarters, the Vinylman bleating out a scratchy rendition of Auld Lang Syne as my block-headed colleagues, with their peaceful drawn-on smiles and conical party hats, tap on their ochre keyboards with spaghetti arms, I think: Oh my god, I love video games. Blendo Games' Quadrilateral Cowboy is kind of a special one, though. The charming, surreal aesthetic -- big, softly-toned polygons and tiny object details -- that Brendon Chung cemented with games like Thirty Flights of Loving and Gravity Bone is on show, but the sense of having fallen into a beautiful machine goes a step further here. It's a game about hacking, in the rough 80s-style Gibson fashion, with chunky "decks" full of programs and a wild workshop glowing with test patterns and big, touchable buttons. On a surface is a box of snacks -- "Spinal Crackers" -- and I'm just immediately in love. I forgot about Neuromancer's "console cowboy". "I love the imagery it conjures," Chung tells me, "the frontier, desperadoes, lawmakers, lawbreakers, lone wolves. Part of Quadrilateral Cowboy involves getting paid under the table by a number of grubby corporations, so the lawlessness of the wild west seemed to fit the spirit of the game." I've built a bug-eyed machine that sits in our workshop underneath the monitor bay, and I commit all my heists in a simulated world, where my deck and I can open locked doors, summon codes from pneumatic tubes, and turn off lasers through the power of pure code. Every environment is a puzzle of machines.

I'd been a little bit worried about this bit of it, to be honest, but it's no time at all before I'm typing things like "telnet" and then "door3.off(3)" and as long as I have my deck with me the world behaves as I want. The raw, test-environment feel of my virtual-reality heists makes me feel like I'm in the guts of the game itself, and it feels amazing. I'm trying as hard as I can to explain it, because I didn't want to try it either, because I didn't think I could do it. Chung says he's had that experience at expos when showing the game: "When I finish my spiel to a passer-by, they'll often start to drift off to a different booth, and I have to wrangle them back in, because seriously, who wants to play a game about programming? It can be a tough sell." "What I'm most encouraged by is that once they start playing, there's a little moment where things click," he says. "There's a little moment where they realize a command terminal is not an intimidating monster, and is in fact quite learn-able and actually quite satisfying. The game assumes the player has no programming knowledge, and tries to provide a gentle learning curve." By some happy accident, I ended up playing Quadrilateral Cowboy at the same time as the vintage Neuromancer game for the Commodore 64, as part of an ongoing series on 1980s computer games I've been doing on YouTube. The Neuromancer game is a bear, with a strange "OKL;" input system (versus WASD), and four disks across which the entire experience is stored, so that the player constantly has to switch between them. Yet I've taken a strange joy from its obtuseness, its old texture, and while Quadrilateral Cowboy is of course much smoother and more sensible -- modern game design in a vintage package -- they seem to share a heritage. "I grew up with ancient computers, so nostalgia plays some part," Chung says. "For me, I find there's something great about the analog meatiness of old mechanical things. For example, old touchtone phones. That satisfying ka-chunk when the receiver slams onto the base. That tactile give of each button. The bulky weight of the base. Gadgets nowadays are designed to be sleek, quiet, and lightweight, and I wanted the game to play with things that were the exact opposite." "Practically the entire game takes place in a virtual reality environment," he adds. "I feel there's plenty of games that take place in real-world places with real-world limits, so I figured this was a nice change of pace. Design-wise, declaring everything to be a virtual construct opened things up and allowed another level of flexibility in playing with game rules and UI and fiction."

"Seriously, who wants to play a game about programming? It can be a tough sell."

"In terms of pieces of work that I've looked to, the staples of Neuromancer, Ghost in the Shell, Snow Crash, Thief, Rainbow Six, and Uplink all play a big part," he says of his influences. "Digging into things, Quadrilateral Cowboy is largely made from experiences I had growing up. I spent what seems like a lifetime wrestling with computers, futzing with autoexec.bat and IRQs and EMM386, hoping some arcane string of configuration settings will finally let a game run." Chung also spent time helping his father repair cars, fix plumbing and do carpentry work: "All of these things made me more and more fascinated with peeking into how things work and how systems fit together," he says. "To me, Quadrilateral Cowboy is about having specialized knowledge and fully exploiting that knowledge to bend and subvert things." Chung used id Tech 2 to make his previous games, and its constraints yielded the clean and simple shapes that have comprised the developer's signature so far. Quadrilateral Cowboy is made in Tech 4: "Technology definitely influences design," Chung says when I ask him about tools. "I like to know the constraints prior to working on a project. In terms of my skill set, I know I don't have the aptitude to make a fully-featured game engine. Therefore, the game engine I choose to work with becomes a constant. The design is fully malleable, so the challenge becomes shaping a design that molds well around a given piece of technology." "When I'm introduced to a new piece of technology, what I usually like to do is make a freebie game to get my feet wet. For id Tech 4, my freebie game was Barista 4, a mod about lonely space engineers. I learned a lot from Barista 4: what the engine excelled at, how it feels, and what's possible. Once I have a handle on my constraints, it's only then I feel confident to work on a full-scale project." Chung's previous works have been relatively short -- many of his fans feel they're stronger for that brevity and tidiness. "As I grow older and find myself with less time to play games, I lean toward shorter pieces of work," he explains. Although Quadrilateral Cowboy is intended to be a longer piece of work than Thirty Flights of Loving, it's "intended to be completed in a reasonable amount of time." "This is a vague answer," he concedes, "largely because the game content is still being built and I myself am still unsure how long it will be." With the game mechanics in place, Chung says he'll mostly be working with the level design thus far, planning to release the game sometime this year. "Probably my favorite moment at these expos is when little kids play," he says. "They jump on and start playing Quadrilateral Cowboy without any preconceived notions about how coding is difficult. It's tremendously satisfying to see them 'get' the game." When I was a little kid, I also was attracted to the language of old machines. I spent what felt like an inappropriate amount of time consistently provoking the SYNTAX ERROR IN 10! remark from a blank command prompt. It did feel arcane. Playing Quadrilateral Cowboy feels like that same kind of magic -- you can get your hands all over all kinds of machines, and you can make them talk to you. You can be a cowboy.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like