Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Open sesame.

Arash Hackimi is a video game journalist hailing from Iran. This article was written with editing assistance from Amirhossein Mirzaei and Brandon Sheffield.

When I started my career as a video game journalist in 2005 in Iran, it was widely believed that the inception of the games industry in the country was a very recent thing. We believed we were experiencing the very beginnings of the local medium, with games like Quest of Persia: The End of Innocence or Nejat-e Bandar.

But since then, I've been researching the full history of video games made in Iran, and in the process have discovered there were some earlier games—much earlier in fact, originating in the mid-1990s.

Not long ago, I published an article outlining the Iranian game history as widely as possible through web, print and field research.

In that article, Iran video games timeline: from 1970 to 2019, I mentioned that the first published Iranian video game was Tank Hunter by Honafa Game Studio. But a few months after publishing the article, Ramin ZafarAzizi contacted me via Twitter and sent me some documents about the development and production of his game, Ali Baba, which turns out to have been released in 1995, some months earlier than the aforementioned Tank Hunter.

Documents related to its development go back to 1993, showing an even earlier start to game development in Iran than we expected. ZafarAzizi has handily compiled a package of documents, including reports in magazines and videos, the game’s source code, and even the official governmental registration of the game in Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology.

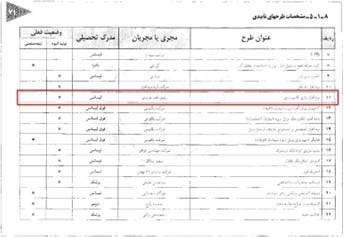

Report of Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology 1994- Page 71

This is the story of what we now believe to be the very first Iranian video game: Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

But first, let's briefly discuss what was happening in games and technology as a whole in Iran from 1979 to 1989 to paint a better picture of the environment ZafarAzizi was coming from.

At the end of 1978, the monarchy of Iran was overthrown. The Shah (King) left the country for the United States, and after a few days, the current government, known as the Islamic Republic, arose.

The country, by any description, was in turmoil. Revolts were happening all over; multiple acts of violence, not limited to assassinations, roadside bombings and terrorist attacks, were commonplace, and eventually resulted in the very infamous Iran Hostage Crisis.

The Iran Hostage Crisis refers to the day a group of people, mostly consisting of pro-Islamic revolutionaries, broke into the US embassy and captured 52 Americans as captives. The result was a lasting animosity in the US government against Iran, which manifests itself mostly in terms of sanctions, which have continued (and increased) even today.

In September 1981, Iraq attacked Iran and the country was embroiled in a war that lasted for more than eight years. This war finally came to an end in the middle of 1989. All that is to say that from the Islamic Revolution through to the end of the war in 1989, all social and technological progress in Iran had halted completely.

With the war ending, and with it endless thoughts of hopelessness coming to a stop, people started to recognize some of the advancements and progress that had happened outside of the country in the last 10 years.

The very first video game consoles—mostly consisting of Atari 2600 and Pong clones—and PCs were imported to Iran; albeit as grey market devices without the involvement of official parties and the companies. After ten years of idleness, the flood of video games had begun.

Magazines gravitated towards writing reviews and educational articles about video games. People who had been teaching themselves about computers got very interested in these games, and with computers and game hardware finally accessible to regular people, this set the stage for the possibility of game development in 1990. As far as we know, ZafarAzizi was one of the first to take up the charge.

Ramin was born in February 1967 and graduated with a BA in graphic design from Azad University in Tehran. He had an artistic childhood, working in woodcraft, writing stories, drawing, and creating electronic and mechanical devices. He had also learned to create electronic music all by himself.

When he was 16, he designed a mechanical engine that was registered as an original invention in the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology. At 18, he wrote a sci-fi novel called The Strange Journey and it got published in a magazine called Javanan as a serialized story.

Ramin worked in his father’s toy shop, selling computer software and hardware in a small corner of the shop. This is where he gained access to computers and computer software, and he made Ali Baba there in his off hours.

“Maybe the most important reason that I got engaged in video game development is that a video game is a complete ecosystem.” Ramin says. “You can create a new world from scratch and it is the only type of media that is interactive. These features were extremely attractive to me.”

“At that time there was no internet in Iran and also no textbooks or articles about game programming. I was an expert in Basic programming already, because I had started the Basic programming on ZX spectrum, Commodore 64, and later on Amiga.”

“But the Basic language was not complex enough to make a complete video game, because it was very slow and didn’t have enough functions. So, I started to learn Assembly and Qbasic.”

“The story began when I wanted to simply move a character smoothly on the screen and that was all. But because I worked on the project in the toyshop, some friends and also other programmers used to come to the shop and we discussed on how to do so. One day, a friend told me: It is absolutely impossible to do so! And this was the driving factor for me to stick to the project and make it happen.”

Even though Ramin finally was able to move the character the way he wanted, another programmer friend of his insisted that it would not be possible to develop a video game in Iran because there were not enough resources to help him in the field. Again, this one sentence was enough to push Ramin to stick with the project. As with so many video games, Ali Baba was completed to spite the odds!

Ali Baba is a 2D side scrolling puzzle platformer, very similar in its gameplay, art style and animations to Prince of Persia (1989). All programming and art asset creation was done by Ramin ZafarAzizi, with the consultation of Ms. Farokhzad Mousaei in color correction and some drawing advice.

The software used for digital painting was Deluxe Paint and all assets were created using a trackball mouse. The game consists of about 140 art assets and it has 5 levels. There is also a cutscene between each level.

The name was taken from the ancient story Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves which is part of the epic One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights). Even if you’re not familiar with the story of Ali Baba, you have definitely heard the magical phrase: Open Sesame!

At the end of 1995 Ali Baba came out. Most copies were sold in the toy shop and a few copies (about ten) were also sold through other stores. After a few months, Ramin is invited to do some interviews with computer magazine.

In 1997, the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology gave Ramin a booth to present his game at the Tehran International Expo.

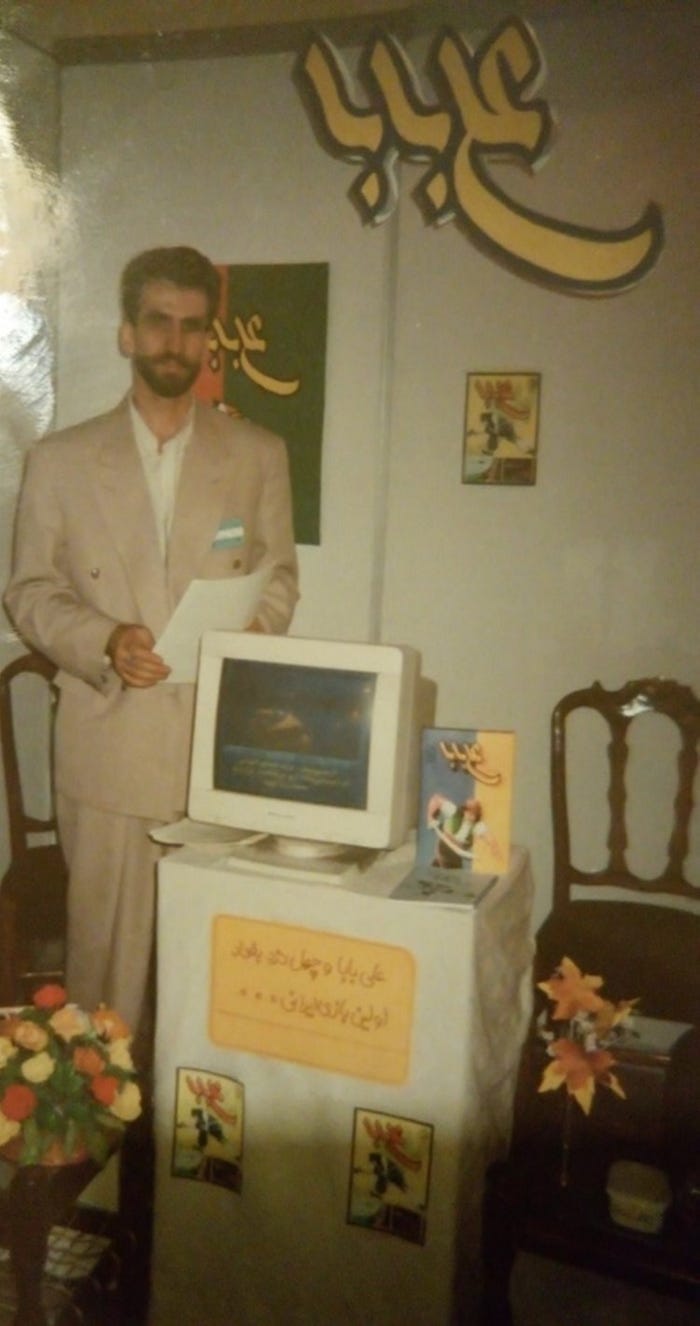

Ramin ZafarAzizi standing in his booth at the Tehran International Expo, 1997.

Later on, in 1999, he participated in the first Multimedia Expo in Tehran.

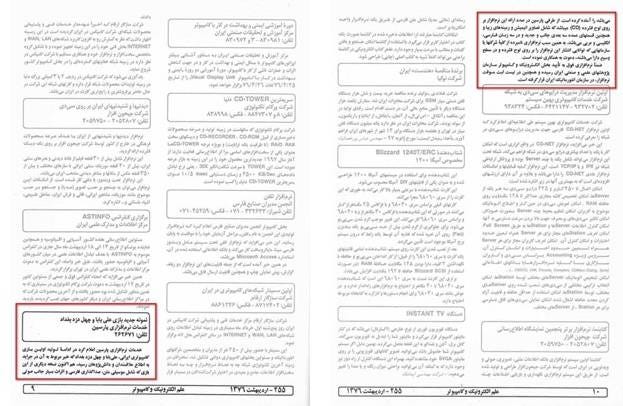

In October 1995 an Iranian computer magazine called Elm Electronic va Computer (which is still publishing today) conducted an interview with Ramin ZafarAzizi, and published it in November of the same year (issue 243).

The title says: "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, The First Iranian Computer Game."

In a later issue of the same magazine (April 1997, issue 255) we can see a short news article that tells us about the existence of a more complete version of Ali Baba. A new version of the game had been developed with music and more sound effects and Ramin calls for any publisher to contribute. The second version has Persian voice acting, three different languages including Persian, Arabic, and English, and the article says a few more cutscenes and also some 3D levels have been added.

Elm Electronic va Computer, April 1997, issue 255

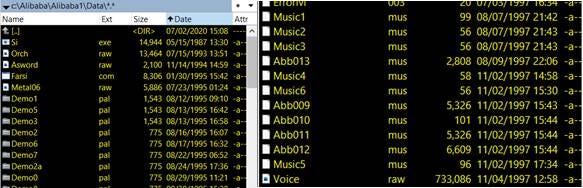

The "1997" date that could be seen in the screenshots of source files, means that the version of the game that I have is the second, improved version.

Screenshots of the source files of Ali Baba that I have on my PC (take a look at the dates).

In the same year, another Iranian computer magazine wrote an article about Ali Baba and called it the first Iranian computer game ever. The former magazine called Rayane (“Computer” in English) in its 42nd issue wrote a one-page review of Ali Baba. It starts with: "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves is the first Iranian computer game developed by Parsin Soft Studio" (Ramin’s Studio).

The title says: Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves is the first Iranian computer game developed by Parsin Soft Studio

Above: Magazine contents that covered Ali Baba

In 2000 the national TV of Iran invited him to talk about video game development in a four-session TV program.

Above: Ramin ZafarAzizi talking on Iran National TV about game development (2000-03-29).

Though Ramin may be the first Iranian game developer, there is another Iranian developer named Maham Samanpajouh who developed the very first Iranian Commodore 64 video game called Beauty and the Beast (1996) during the same period. He also had to market and represent his game all on his own. But this is not the story of Maham, and we’ll get to him in another article.

Unfortunately Ramin and Maham's efforts were not particularly successful, and they couldn’t sell enough copies. Ramin says despite all the press he was only able to sell about 130 copies, and Maham doesn’t know exactly how many copies the publisher had sold, but he guesses around 200 to 230 copies.

Ramin says that "the market was not welcoming in this case, because they thought it was risky and didn’t want to invest in an Iranian video game."

At that time almost all video games were bootlegged in Iran, and Iranian publishers could easily copy and sell them, without any negotiations with the original publishers and developers. They didn’t pay any royalties for the best of the best from outside the country, so why would they invest in a local product?

In a market where you can easily copy and sell whatever amount of Prince of Persia 2 (1992) or Flashback (1993) or Doom 2 (1994), why should an investor risk on Ali Baba?

Sadly, this situation still exists in Iran today.

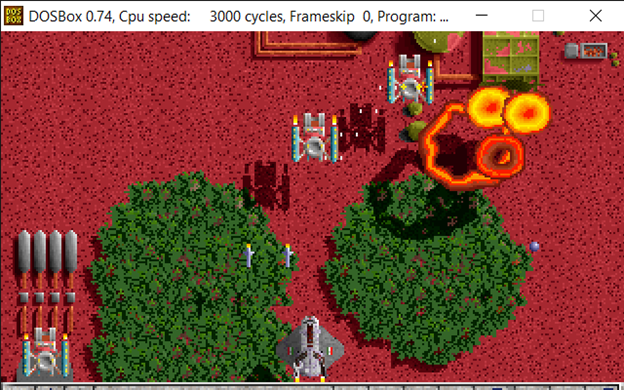

After publishing Ali Baba, Ramin started to develop another game called The Big War. The Big War was completed, but Ramin couldn’t convince any investors to invest in its development or even publish the game. So, after five years of development and creating two video games, Ramin had no money left to continue, so he decided to say goodbye to game development.

But after distancing himself from video game development from 2000 to 2017, he was able to procure some money and start the development of his third video game, Zoono. Zoono is now under development.

In the 276th issue of Elm Electronic va Computer magazine, October 1998, a news article was published which said: “The Second Iranian Computer Game is going to be published soon.” This was also Ramin’s game, but it never got published.

Even if it had managed a publishing deal, it wouldn't have been the second Iranian video game, because another game studio called Honafahad managed to publish The Tank Hunter and Devil’s Death, among other titles, in 1996 and 1997. 1996 Is also when Maham Samanpajouh and Reza Shamsian ‘s Commodore 64 video game Beauty and the Beast was published.

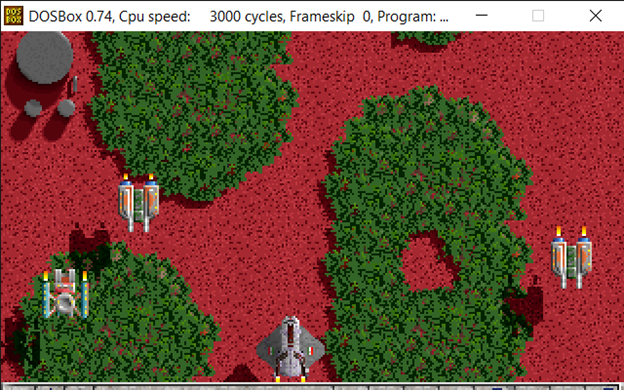

The Big War was a top-down shooter and a clone of Raptor: Call of the Shadows 1994 for PCs.

Recently, Ramin has returned to video game development with his new studio Rahamin and is working on his latest game called Zoono. Zoono seems to be a Limbo-like action-adventure game and Ramin is the sole developer on the project. This time Ramin is not waiting for investors to contribute, and he has managed to stick to crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and Patreon.

A screenshot of Zoono by Ramin ZafarAzizi. The game is currently in development.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like