Interview with Tobias Ruskan, lead designer and producer at Saibot Studios, known for the horror saga, "Doorways".

This interview serves as an appendix for "Game Development in Latin America"

Tobias Rusjan, founder of Saibot Studios [Source]

Q: Could you please tell me a little about your position at Saibot Studios and your history with the studio?

A: What I do in Saibot Studios is directing, programming and game design too, but mostly directing. I’m in charge of controlling a little of every area, program and work the mechanics and make sure they work properly.

I am also into the media part and public relations, but it’s mostly what I mentioned before.

Q: How many people are there in Saibot Studios?

A: Right now we are seven people.

It has changed a lot. At the start we were only two but then it grew to three, four, five…

Shortly ago we finished the Doorways Saga and started with a new project that is still in “Top Secret” phase.

But yeah, the current team is made of seven people, that’s how many are in development.

Q: Were the Doorways games the first ones you made or is there something before that?

A: Yes. As Saibot, it [Doorways] is the first game [we made], the first saga.

I worked in other companies in the industry, but as Saibot Studios and indie developers, it [Doorways] is the first saga.

We released three games - actually four. A short time ago we released a free game that is an old prototype made before the whole saga - as part of Doorways.

Q: What inspired you to get into game development?

A: Personally, I started very little -- when I was in elementary school. To be honest, I played [video games] as a kid just like everyone, and I found fascinating being able to create something myself that could create a reaction in other people and that they could experience something created by me. I think that’s what motivated me to start developing. I love playing games too, but I still like it more being able to make other people enjoy something you made. I find it interesting.

Q: How did you start to make games?

A: The first thing I made related to video games was working with the “DIV”. I don’t know if you have heard of it. It’s a program [used] to make games, developed by Hammer Technologies, which disappeared a long time ago.

I started making little things without having an idea [of what I was doing]. For example, I would take other games and change the code, or the sprites to try it out. That was back when I was younger, I would have been twelve or thirteen years old.

Then I started studying programming a little more specialized. I also got into that career in Image Campus -- which is something we have here in Argentina that is some sort of third party [foreign university]. There I learned a couple of more things, stayed for a year and a half, and then I started to work in the industry when I was nineteen years old for a company, that also disappeared, called GlobalFun, where we made games for cellphones.

Then I did a lot of small things on my own, trying things out. Until [one day] after working around five years in the industry I began to work independently and we formed this [company] that we named Saibot Studios.

Q: What drew you to such niche, difficult genre as it’s horror, with the Doorways series?

A: Well, since I was little, I always wanted to make “hardcore” games, games for “gamers”. Here in Argentina there is a lot of the “casual” market, but I actually always wanted to make games for the “gamers”.

I always liked horror -- the gore and the dark touch. I found interesting what Frictional Games originally proposed with Amnesia: The Dark Descent. I found interesting the part of immersion, it [Amnesia: The Dark Descent] was super immersive. Originally Doorways came from a project I presented in the company I worked in back then, in 2011, NGD Studios. I was allowed to present a project for the company and I tried looking for something that I liked but that at the same time was possible to do.

Originally the game wasn’t even going to have enemies or characters. It was some sort of exploration game of distorted worlds and then when I met Amnesia I saw there was the possibility to introduce some really basic characters to the whole stealth thing.

I found that very “cupped” [1] and mixed these two things, along with the horror touch that was very popular back then and that I always liked. Doorways was the result, a sort of blend that takes a lot from Amnesia, Outlast, the aesthetic of Silent Hill but with its identity too, its own little things. But I would say it’s mostly a mix.

Doorways: Holy Mountains of Flesh (2016) [Source]

Q: Do you feel like your nationality influenced your work?

A: What I see here in Argentina is that while there is industry, it needs to grow a lot. We need to grow a lot. When I finished high school I saw that there was an industry (I didn’t know there was one [before that]) and that helped. A lot of things I had to do on my own (learning and stuff), but I think that [getting into the local industry] helped and it also makes one to stand out more.

There is more industry than what people generally think. If I had been born in a first world country (United States, Canada, some country in Europe) I would have helped more to entrepreneur this [game development] in the country.

But it’s not something that played too hard against us. The people in the industry are very nice -- they support one another to learn and grow and try to show off in the market. I think it [Being born in Argentina] was fine, it didn’t play 100% in our favor but there is a good response from the people. What doesn’t help at all is the market. Yes or yes [2] one has to aim to the outside because here there is a lot of piracy, it’s no place to make a living from this [making games]. If you want to, you have to aim to the outside (that is, internationally).

Q: What are some of the obstacles you have encountered while making games in Latin America?

A: I think it comes from that same direction: The market.

The thing is, the stuff made here (in our case with Doorways) is very well seen by the Argentinian public, but the reality is that when it passes into the international market, you are just another one [developer], just another one in the pile.

Most of what is independent has a lot of quality and it’s very difficult to compete with what’s outside, so we are left at a disadvantage when trying to get into the international market. One goes with an idea, thinking that one has something interesting and the reality is that it’s just another game.

There was some difficulties on that side, and there also may be a lack of trained people. There are good people here but we need more trained people -- more studios that teach, more companies that train. That side has also played against us.

The advantage is that one can help [with] all of this since we all gotta start somehow. We are part of that growth too, which is good but there is still a long way to go for the country.

Q: I have heard one of the problems, at least in the south part of Latin America, is the distance to the United States. Do you have problems with that or have you found a way around them?

A: The physical distance? No, I don't think it influences. Nowadays with the internet, it [being close or far apart] is more or less the same; if there is a political problem between a country and another that’s something else but that’s not the case with us at least. The relationship of Argentina with the United States is the same Uruguay or Chile have. I don’t think distance is an issue. If we were in Europe there would be a difference.

Though, there is something that distance may affect. If one wants to assist to an important event in the United States, it probably would be more accessible to live in Central America. That’s the only thing I can think of. If one had to move, then the distance would influence, but apart from that I think with Internet it’s all pretty much the same.

Q: How did you overcome these obstacles?

A: One of the obstacles I mentioned is the lack of trained people. Here one of the things we try to do is to get beginners that are not very trained but that have a lot of desire to learn and stuff.

When we started with Saibot we hired people that had a “base” and a lot of desire [to learn] and made them learn the rest. That’s one of the ways to overcome it [the obstacle].

Right now since we have grown a little, the people that get in are usually people that are already trained. We no longer train as much because we now spend a lot of time developing, so we don’t have as much time to train people. At the start we had to do it because the [economic] investment was very small and we had to produce a game with that. It was a different situation, and that’s one of the ways we found to overcome the obstacle of training people living here.

The Saibot Studios team [Source]

Q: What do you think of the education regarding Software Development in Latin America?

A: I can tell you what I know about here in Argentina, I don’t know about the rest of Latin America. Here, there’s been progressively more courses and careers in respect to video games, which is good. The problem is that there is not enough experience here for there to be people that retired from the industry so they can teach. Most of the people that teach are people that read things online and played a lot or developed a little, but we need more people with a lot of trajectory (experience) in the industry to do classes on it.

There are a lot of initiatives, places like Image Campus, Da Vinci [School] and others (I even heard they started [offering] a career on that in the UTN). It’s great that they started expanding from software [development] directly to video games. I find that really “cupped”[1] but it also still needs to grow up. I think everything is growing up, but there’s still a long way to go, that’s for sure.

Q: There is a question I did before, but I may have formulated it wrong. Do you feel being raised in Argentina influenced your work? In the themes it touches on, how it does it, etc.

A: Huh, well, yes really. Mostly in the last Doorways game (each chapter of Doorways is about you [the protagonist] chasing a maniac, and each one is from a different part of the world), in the last game [Doorways: Holy Mountains of Flesh] the protagonist is chasing an Argentinian, and the places one passes by are places here in Argentina (distorted, obviously). There is a lot of influence from here, like finding Mate[3] or a painting with Saint Martin[4], things like that, references. As a matter of fact, the enemy is known as “El Asador” [The Roaster] and here we give a lot of importance to roasted meat, so it’s mostly traditional things, touches really. On that side I think you can see the influence of the country, I like a lot leaving that national mark but it’s more like a condiment, something to leave the mark there. I think that’s most of the influence.

Now in how one manages [a game studio] and such, I think there may exist an Argentinian touch. But I wouldn’t be able to recognize it or tell you what things were influenced by it [being Argentinian]. My energy comes from cooked Mate[5], but apart from that I wouldn’t know what to tell you. I think the references in the games are the “top ten” influences for me that I like to put into it. But beyond that I don’t think there’s much more.

Q: Are you aware of other Latin America game studios?

A: Yes, in Argentina mainly. Though to be honest I should know a little more about the rest of Latin America. I know there’s “movement”: Some in Brazil, a lot of things in Chile, a couple in Uruguay too, in Mexico too but I really don’t know about specific companies [there]. But I do in Argentina, I can tell you about those.

Q: Can you give me some examples?

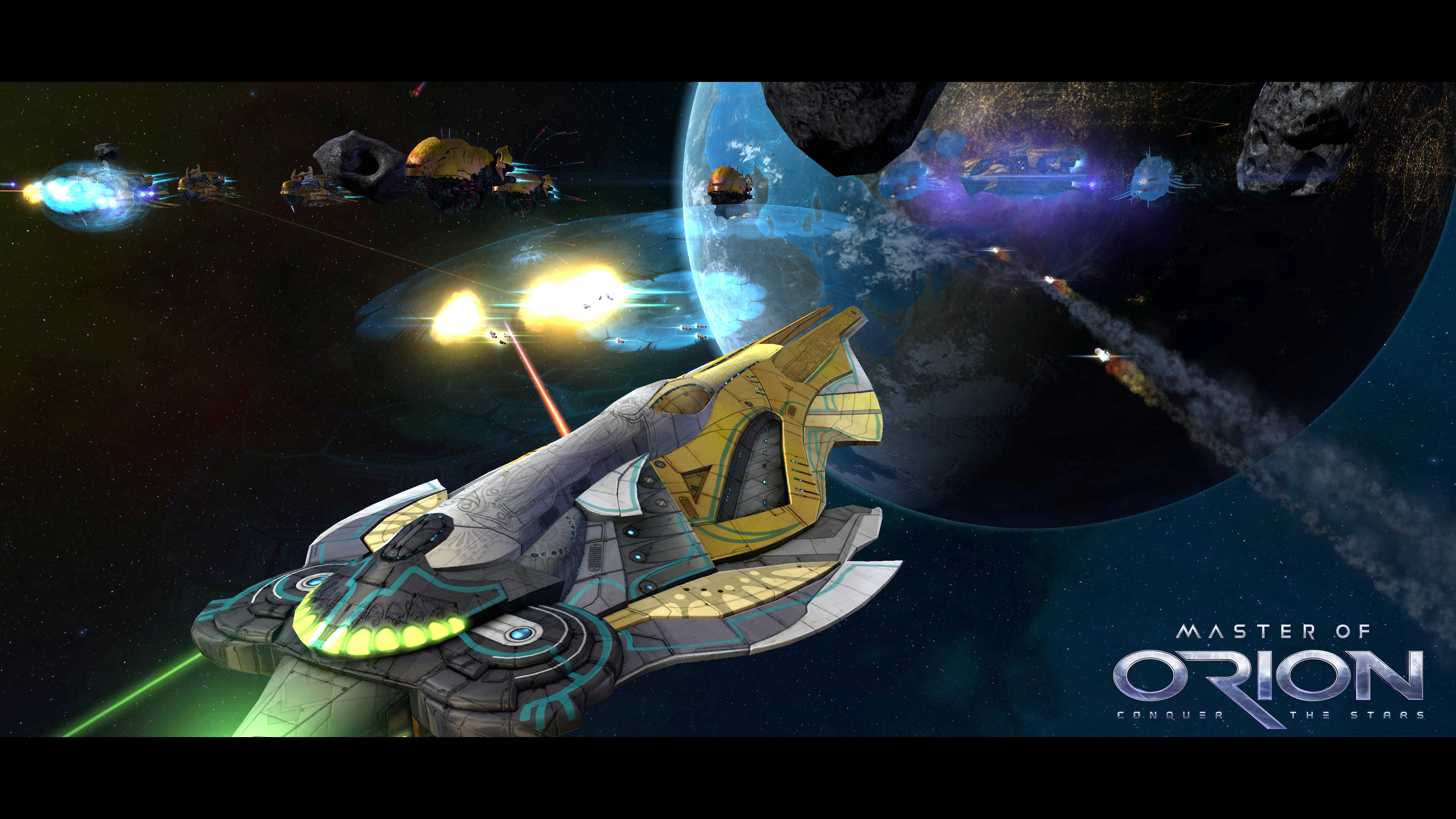

A: In Buenos Aires the biggest one is NGD Studios. They released “Master of Orion” this year, I don’t know if you have heard of it. It’s a strategy game that they did a remake of and it [the remake] got a lot of recognition. It’s the first Triple A game made here in Argentina. It [the studio] is led by Andrés Chilkowski among others (almost 40, 50 people [Working there]).

There’s also a lot of moment of online games and games for smartphones, there is a lot of that here, especially in the more commercial part with companies like Dedalord; there are companies that serve as third parties like Ravegan from Cordoba [part of Argentina]. There’s also a lot of independent [companies] like Senscape, the people that made Asylum; Scratches [made by Nucleosys]; [there is also] Daniel Benmergui who used to be a lone developer but is now working with other people and recently published a game in the Humble Originals. Those are the most recognized ones, all things considered.

[He sent me a link with a list of recognized developers in Argentina]

But yeah, there is a lot [of developers] in the commercial part. A lot in smartphone, mobile, web and progressively more for “hardcore” games. There are more and more but I wish there were even more. It would be good since that’s what really everyone wants to do.

Master of Orion (2016), made by the Argentinian team NGD Studios [Source]

Q: What do you think of the industry in Latin America and what do you see in its near future?

A: It’s growing. We need people from the outside to come and instruct us in a lot of cases. Some companies (with enough money) do that, the problem is that they only do it for themselves.

There is a lot of movement for events here in Argentina, for example the ones organized by ADVA, the Argentinean Association of Development of Video Games [in Spanish: Asociación de Desarrolladores de Videojuegos Argentina] that is really also involved with Latin America in general. Events like the EVA [Argentinean Video game Expo or Exposicion de Videojuegos Argentina in Spanish], I don’t know if you know of it -- it’s an event that’s done every year and they bring people from the outside that do seminars. Actually I did a seminar recently in the last EVA, talking a little about our movement [referring to making Saibot].

I think those things are good, but we still need a little more. We still need to insert ourselves a little more in the general panorama, [and] try to bring people so they instruct us. One of the problems I see is that a lot of talented programmers and artists leave to the outside (with outside I refer to countries of the first world) because they find a “roof” [limitation] here or they get a better salary in the outside, and that’s understandable because it’s normal to get paid more outside but at the same time that doesn’t do well to the local industry because that’s lost talent. I see a lot of that -- it has happened to me. Someone leaves us to work for a company that is from here but does third party in the outside or people that directly can go to the outside. And while that can be good for every person, it doesn’t benefit the local industry because that talent is lost.

I think that’s the case in all of Latin America. It needs to grow a lot and try to make people stay here, but for that people there needs to be something [to incite them] and we lack that in our growth.

Q: What are your plans for the future?

A: We depend a lot on how Doorways and the next project do. We are very tight on the money, we are even looking for investment and subsidy to endure as much as possible. The idea, if everything goes well, is to try to grow as much as possible to make games progressively bigger. Obviously it’s hard to make things of a triple A quality in small teams. Nowadays, I think it’s more feasible because of the available tools but it’s very hard on a budget level, because a Triple A game needs a lot of people and a lot of budget.

But yeah, the idea is to make games progressively bigger, the thing is that we are still a little “enclosed” and have the things very hard on that side.

Q: Any additional comments?

A: I think we covered everything.

It’s important that more companies emerge. I see a lot of people awaiting for the miracle of receiving money instead of sitting down and looking up how games are made, something that doesn’t really require one to pay an institute. One can study, practice and make small games on their own. I don’t know if you saw a seminar I did the other day that I recorded and uploaded, I will send it to you later if you are interested. There I comment on what’s best for the industry, because I want to incite other teams and I think that could help the industry a lot, not only here in Argentina but on the rest of Latin America because I think there’s a lot of talent and desires, but we need a “push”, which is also something I talked about in the seminar to incentivize other teams. I believe that would be the “final” comment.

Q: Thank you very much for your time, I will send you a copy of the paper later if you want.

A: Sure! It was a pleasure.

This interview was translated from Spanish as directly as possible to reflect the idiosyncrasy of the country where the interviewee is from.

[1] Argentinian colloquialism. Is used the same way as “cool”

[2] Spanish colloquialism. Means “Like it or not”

[3] Argentinian beverage

[4] Argentinian national hero

[5] Argentinian beverage

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like