This excerpt from "Video Games as Culture: Considering the Role and Importance of Video Games in Contemporary Society" examines how games can help players access other experiences and realities.

The following excerpt, parts of a chapter from “Video Games as Culture: Considering the Role and Importance of Video Games in Contemporary Society” by Daniel Muriel and Garry Crawford, may be useful to game developers in order to understand some of the key elements that make video games windows that enable the player to access other experiences and realities. It is based on chapter five, “Video Games beyond Escapism: Empathy and Identification”, where video games can be seen as mediation devices that allow players to experience situations that they have not had or would not have otherwise.

This excerpt is part of a book that considers contemporary video game culture, which provides an important lens for understanding crucial aspects of contemporary society. Drawing on new and original empirical data, including interviews with gamers, as well as key representatives of the video game industry, media, education and arts, the book will appeal to upper undergraduate and postgraduate students, video game scholars, media and cultural studies researchers, and those involved in the video game industry and media. “Video Games as Culture” was published in March, and is available for order on Amazon or directly from publisher Routledge (20% discount using the code FLR40 at checkout ).

Introduction

We frequently associate the act of video gaming with escapism. That we play video games in order to escape the ordinariness of our everyday lives is a widely accepted idea. It is often suggested that video games provide opportunities to build an alternative or parallel reality in which players are able to live an immersive experience far from the ones they are having in their regular lives. In this sense, video games are helping create a new range of social and personal experiences, but by doing so, they are not only fostering escapism, but they are also enabling connections with other aspects of social reality.

Numinous Games' 2016 release That Dragon, Cancer

Escapism is indeed an important part of why people play video games, but it is not the only cause or consequence of video gaming. We would suggest that, far from escaping from reality, video games can also connect us with (other aspects of) reality in surprising and unexpected ways. For instance, video games can help us put ourselves in the shoes of others and provide new experiences. Video games work then as mediation devices between players and reality, which could potentially, encourage players to empathize with different, even extreme, situations – such as, civilians in a context of war in This War of Mine (11 bit studios, 2014), parents of a boy with cancer in That Dragon, Cancer (Numinous Games, 2016), migrants trying to pass through a border post in Papers, Please (Pope, 2013), or groups living through a scenario of social catastrophe in The Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012).

[…]

Escapism and video games

According to Yi-Fu Tuan (1998), escapism is inherent in human culture. It is a notion that, ironically, human beings cannot escape from, and can be found in times, places, and practices as distant as the prehistoric era, Disneyland, shopping malls, religion, the contemporary city, imagination, and cooking. Escapism implies ‘going from somewhere we don’t want to be to be somewhere we do’ (Evans, 2001: 55), and this place we seem to desperately want to escape from always points to the notion of reality. This outlines then a canonical definition of escapism as the process through which we (temporally) escape from some aspects of our current reality, such as boredom, work, routine, or stress, for example. However, having defined escapism as about getting away from ‘reality’ (even though we acknowledge that ‘reality’ is a concept that is particularly difficult to define and filled with multiple nuances), we are still left with an unanswered question: where are individuals escaping to?

Lucas Pope's Papers, Please, released in 2013

This idea then, seems to suggest that people seek relief and shelter in places in which their current socio-material conditions of existence – what we know as reality – are suspended or altered in a way that, typically, makes them, for example, more pleasant, safer, under control, or more exciting and thrilling. In this sense, virtual versions of reality – imagined (Tuan, 1998), simulated (Evans, 2001), or staged (MacCannell, 1973; Pine and Gilmore, 2011) – appear to be preferred destinations. In particular, taking into account the argument that we live in a digital age, as we saw in Chapter 2, video games could be seen as one of the most typical contemporary forms of escapism. Moreover, according to Gordon Calleja (2010: 336), it is possible to assert without exaggeration that ‘digital games are considered the epitome of contemporary escapism’.

This is the case for many of our interviewees, who stated that one of the main reasons they play video games is to escape from their daily life problems and routines:

I also play because of that, because it helps me to break away […], it’s my time to chill out (Iker, male, 43, regular player but not self-identifying gamer).

For many of our research participants, video games are, at least partly, about escapism, and they expressed their wish to be transported to a different world where they would be able to live diametrically opposed realities from those they experience normally. Thus, video games involve an idea of escapism realized through the realistic fiction of entering in an alternate-reality: ‘Sometimes I wish I could be transported to this world and just live that part’ (Carl, male, 28, self-identifying gamer). Hence, our participants identify a movement across a boundary line between reality and the video game, and then, articulate this boundary-crossing as an escape from the vicissitudes of the real world to the pleasures of the video game universe. As we find in the following definition of video games:

I guess it’s an interactive experience, yes, for temporary escapism, for different reasons. A medium to tell stories, like a place to escape to, something safe and fun (Albert, male, 25, indie developer, game artist).

Playing video games is, for this interviewee and many others, a place to visit, a location to escape to, a space to inhabit; it is also (typically) a pleasant experience: enjoyable, safe, and fun. The experience of video gaming is defined by the elaboration of an alternative reality, detached from the one players normally live in; a reality that is construed as a better version of its mundane counterpart, which is usually riddled with routine and boredom.

[…]

However, as Alfred, a 26-year-old dedicated video gamer, argues, ‘escapism is just a part of the experience’. For him, playing video games is ‘half and half’, adding that there is ‘definitely an element of escapism’, but that it is also about keeping ‘in touch with people’. Alfred also narrates how he often has conversations with friends and family about out of the game matters while he is playing, and will shift in and out of focusing on the game, depending on the level of attention needed at a particular point. Hence here, Alfred is describing a continuous process that does not make clear distinctions between the game world and everyday life. Gamers articulate both the (perceived) distinctions and continuities between the two (or more) realities. They speak in terms of ins and outs, ons and offs, entering and exiting, but also make connections and recognize overlaps between both universes. In the end, according to Pawel Miechowski, the developer at 11 bit studios (creators for This War of Mine), escapism is undoubtedly part of the appeal of video games, as gamers often ‘want to run into power fantasy’, but escapism ‘is not everything’ because the ‘world isn’t such’. For a game to be enjoyable, often they have to retain, at least some sense of believability; the fantasy has to connect to some sense of (alternative) reality. And therefore, we would suggest, that video games might also lead the player toward not just escapism, but also empathy, identification, and connection to other roads.

Connecting with other realities

As we write this book in mid-2017, we are sadly witnessing an endless amount of news, images, and discourses on the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis. But this is not a new phenomenon. It is merely the latest version of a story told many times, which narrates the tale of those human beings who are seeking something very simple but, apparently, very difficult to achieve: a better life (or simply just a life; since it is often for many, a matter of life or death). They escape from war, famine, misery, all kinds of persecutions. It does not matter what awaits them on the other side of the multiple frontiers they have to cross, they are ready to risk their lives to escape the horrors that make up their current situation. Border after border, these people only yearn for one thing: to reach their destination.

11 bit's This War of Mine, released in 2014

The frontier – that liminal space – is a place between two places; it is a universe with its own rules and meanings, which are different from those we find on both sides of the border. The frontier is a transit area but it is also a detention zone, where the authorities decide who enters and who stays out. It is in that paranormal borderline sphere where Papers, Please (see Figure 5.1 below) takes place. In this game, we put ourselves in the shoes of an immigration officer at a border checkpoint, dealing with the people piled up on the other side of the border who want to enter our territory, the (fictional land of) glorious Arstotzka. The player spends most of the time checking documents such as passports, work permits, IDs, visas, and vaccination records, with the task of deciding on who enters into the country, and who does not.

It is widely accepted that Lucas Pope’s game, Papers, Please, recreates a frontier that reminds us of a former Soviet republic. It is almost impossible not to notice that the game features all those things that we would typically associate with what happened on the East side of the Iron Curtain: from the fictitious names of the countries to the dull aesthetic that impregnates its whole design, characteristic of the Soviet bloc. However, the more time we spend as Arstotzka’s frontier inspector, the more it reminds us of the present. Passports, id cards, work passes, forms, entry visas, frisks, augmented security measures due to terrorist threats, full body scans, inquisitorial interrogations, deportations, detentions, use of deadly force, and so on. Is all of this just the realm of extinct Soviet republics? Or is this closer to how the frontiers of advanced Western democracies work; especially in these moments of global distress, where millions are being forcibly displaced worldwide?

The player has to make a tremendous effort in order to survive and provide for their family because everything depends, to a great extent, on how efficient they are in managing that crossing point we call the frontier. That means we are forced to leave several human beings behind, maybe abandon them to a terrible fate; people who wish to be reunited with their family, who might be victims of abuse, exploitation, and persecution. But if the player helps them, they will be punished and have consequences later, affecting the in-game player’s own family welfare. The player will be forced to face the consequences of their actions, like not being able to provide their own family with food, medicine, and heat, or having to choose which of their family members receive those vital elements.

Fortunately, Papers, Please gives the player some leeway to, from time to time, make decisions that are against the rules and regulations: smuggling products, accepting bribes, letting people in danger cross without the proper papers, stopping dangerous individuals that are trafficking people, collaborating with a resistance group that, later on, will plan terrorist attacks, and so forth. There is the possibility to poke holes in the system, giving opportunities to those who have none, and trying to help yourself and your family. The player might be creating a greater evil or damaging their own interests, but at least they are able to negotiate beyond the limits of this frontier. Papers, Please is about embodying the bureaucrat; assuming the role of the dull civil servant. However, it also allows the player the opportunity of becoming the saviour and the ally of pariahs; the anarchist working from the heart of the iron cage.

But our question is: is this a reality we would like to escape to? Does a video game like Papers, Please offer an attractive universe that invites players to get lost in it as a break from their daily lives? Is this video game avoiding reality or, actually, chasing it? Although Papers, Please puts the player in a frontier inspector’s shoes, it is in fact connecting them with wider social issues; it is giving players an experience of migration processes, global security, modern politics, abuse, responsibility, abandonment, and similar socio-political processes and consequences. The game puts the player in thousands, if not millions, of people’s shoes. And the popularity of Papers, Please, and similar games, would seem to suggest there is a desire (at least for some) to explore other realities that are less fantasy but more closely tied to the world we live in: ‘I’m more interested in emotionally profound experiences […] something which pushes those boundaries’ (Edward, male, 54, head of a master on video game development).

In this sense, Jordan Erica Webber (2017a: online), co-author of the book Ten Things Video Games Can Teach Us (Webber and Griliopoulos, 2017), argues that video games are potentially ‘a compelling medium through which to engage in philosophical thought’. This implies that video games are, unlike philosophical thought experiments that only occur as imagined scenarios, ‘counterfactual narratives that test the player’ in an interactive scenario. Video games offer opportunities to engage in the most varied situations and approach different questions such as perception, personal identity, free will, and ethics. Video games then help connect us with multiple realities and experiences.

However, how does this connection with other realities work? We will explore now two similar and interrelated mechanisms through which video games are mediating in processes that connect players with other realities rather than helping them escape: empathy and identification.

Empathy

Video games have often been perceived, especially by clinical psychologists but also by other media scholars and social scientists (Appelbaum et al., 2015), as a medium that can have a negative impact on their players, particularly in triggering or even promoting violent behaviors. It is not unusual for the media to report on studies that supposedly highlight causal links between increased levels of aggression (particularly among children and adolescents) with the habit of playing video games. In the same way, it is not uncommon to be told that perpetrators of acts of great violence, such as mass shootings, are avid gamers (Scutti, 2016). The assumption that is often made, either implicit or explicitly, is that playing video games supresses any hint of empathy in those who play them; inducing in these video game players a state of personal, emotional, ideological, and social numbness (Dean, 2004).

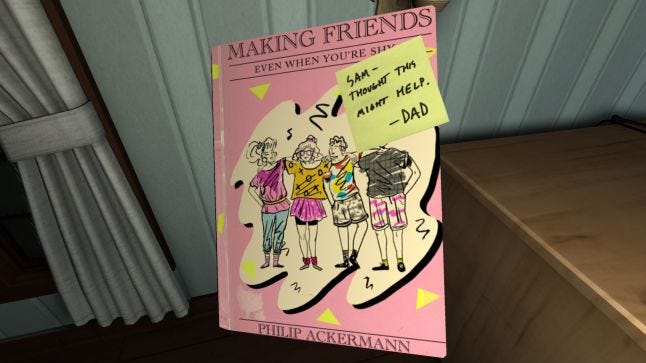

Fullbright's 2013 release Gone Home

However, what we found during our research is the existence of numerous cases in which the participants reflect explicitly on the relationship between empathy and video games. There is even a label called empathy games to refer to certain genre of video games like the aforementioned Papers, Please; a categorization that could similarly be applied to other titles such as Gone Home (Fullbright, 2013), Firewatch (Campo Santo, 2016), Valiant Hearts (Ubisoft, 2014), That Dragon Cancer (Numinous Games, 2016), Cart Life (Hofmeier, 2011), To the Moon (Freebird Games, 2011), Spec Ops: The Line (Yager Development, 2012), Dys4ia (Anthropy, 2012), Depression Quest (Quinn, 2013), Brothers: a Tale of two Sons (Starbreeze Studios, 2013), Inside (Playdead, 2016), and This War of Mine (11 bit studios, 2014). In fact, the last title, according to one user on a comments section of the website GiantBomb, was ‘this year’s Papers, Please in terms of empathy simulator’ (Luck702 in Oestreicher, 2014). Moreover, this was even something that was recognized by the developers of This War of Mine: ‘Papers, Please was a great a game that inspired us to move on with our project, to make an empathy game’ (Pawel Miechowski, male, 40, senior writer). It seems that video games have also embraced a global trend where empathy is, at least in theory, on the rise. This is what authors like Jeremy Rifkin (2010) and Frans de Waal (2009) call The Empathic Civilization and The Age of Empathy respectively, to describe the current transformations in the role played by empathy in the fields of psychology, biology, law, education, politics, communication, social relationships, and economics, to the point of suggesting that empathy ‘is the very means by which we create social life and advance civilization’ (Rifkin, 2010: 10).

[…]

Empathy is a very difficult notion to define because the academic literature, and its popular representations, allude to both mind and body, cognitive and emotional processes, and ontological and phenomenological problems. In some accounts, it could be understood as ‘the mental process by which one person enters into another’s being and comes to know how they feel and think’ (Rifkin, 2010: 12). In this basic definition, empathy encompasses both the emotional and the rational aspects of an embodied, yet imagined, experience.

[…]

Opposing this strong cognitive-driven notion of empathy, the primatologist Frans De Waal […] opts for emotional and embodied engagement as the key elements in the construction of empathy:

Seeing another’s emotions arouses our own emotions, and from there we go on constructing a more advanced understanding of the other’s situation. Bodily connections come first – understanding follows (De Waal, 2009: 72).

[…] Moreover, De Waal argues that, of all bodily connections, facial expression is the most important. The face is depicted as the emotion highway because it ‘offers the quickest connection to the other’ (Da Waal, 2009: 82).

It is not surprising then to see certain video games using faces to put the player in this empathy highway. In This War of Mine every character controlled by the player is identified by a close-up picture of a real person’s face. In fact, its developers photographed themselves, including their friends and family, because they wanted to confront the player with ‘regular people, looking like people you may meet on the street’ (Pawel Miechowski). Gone Home uses drawn – realistic – portraits and pictures of characters – mainly your family – to help the player empathize with them, by putting a face on those whose story you are trying to figure out. Even the simple pixelated graphics used to portray faces in Papers, Please are fundamental in establishing a connection with the situations and individuals depicted in the game. Those quasi-faces parading through the border crossing point remind players that they are dealing at the same time with nobody in particular and potentially anyone, triggering an uncanny sense of empathy towards a problem that might have affected them and their relatives in a more or less distant past, or might happen to them in the future, but, surely, it is afflicting thousands of people around the world as we write/read this.

The importance of faces and their gestures is something that Team Bondi, developers of L.A. Noire (2011), fully understood. Taking on a role of a detective, the player has to solve a number of cases by collecting evidence and, as the key aspect of the game, interrogating suspects and witnesses. Players must decide whether the characters are lying based on their facial expressions. Team Bondi used MotionScan, a motion capture technology developed by their sister company, Depth Analysis, which focuses on capturing facial expressions (Alexander, 2011). Though TellTale have not developed a dedicated technology for facial expressions, they soon realized faces were of the utmost importance in order to elicit emotions among players. The Lead Writer of The Walking Dead’s first season video game, Sean Vanaman, stated that after ‘writing the first episode we start to make lists of the type of things characters are going to feel in the story and then start to generate isolated facial animations to convey those moods and emotions’ (Madigan, 2012). As Smethurst and Craps (2015: 284) suggest, this is how the game represents traumatic events: ‘by showing us its impact on the faces of characters who are suffering through the shock of losing loved ones in harrowing situations’. This means that video games, using the proper technology, can translate emotions expressed by human models into animated facial expressions that will be scrutinized by players, affecting their choices and capacity to create connection channels with others.

Thus, video games are powerful mediators that are able to develop empathic responses in those who play them, mediating between realities and connecting them: the ones inhabited by players in their regular lives and those materialized in the universe of the game.

[…]

This fundamental idea is summarized by Karla Zimonja, artist developer and co-founder of Fullbright, when she was speaking about Gone Home and its potential to show the intricacies and tribulations of an adolescent girl’s life (realizing she is gay, coming out to her parents, her first relationship), but also other mundane stories about parenting, abuse, professional and personal frustration, friendship, infidelity, loneliness, marriage, and so forth:

That’s the thing about video games, they can give you experiences that you can’t have in real life, that you haven’t had, so it can be, hopefully, an experience that can add to someone’s conception of how people are in the world.

Video games, therefore, are able to provide new experiences to players, but ones that are rooted in (someone else’s) lived reality. They facilitate the possibility to ‘step into someone else’s shoes’ and ‘experience the world from someone else’s perspective’ (Harris et al., 2015: 58). It is an open window to other people’s lives, problems, and situations; an open window video games invite us to step through. An invitation that has the potential ‘to foster greater empathy, tolerance, and understanding for others’ (Simkins and Steinkuehler, 2008: 352).

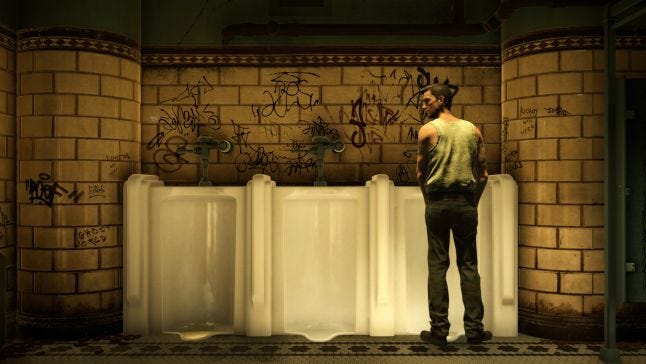

Robert Yang's The Tearoom, released in 2017

This is the case of the video game The Tearoom (Yang, 2017), which is described as ‘a (free) historical public bathroom simulator about anxiety, police surveillance, and sucking off another dude’s gun’, and is heavily inspired by Laud Humphrey’s (1970) classic sociological study of men who have anonymous sex with other men in public toilets (‘cottages’ in the UK, and ‘tearooms’ in the US) (Yang, 2017). In this, its creator Robert Yang, seeks to simulate a public bathroom in Mansfield (Ohio) in 1962, where the player can have sex with other men. According to its developer, Robert Yang, The Tearoom is based on a historical fact; in 1962, the Mansfield Ohio police department hid a surveillance camera behind a two-way mirror in a public bathroom in order to film men having sex with other men. Later, the police department used this footage to arrest and imprison these men under Ohio’s sodomy laws. Thus, in this game, Yang tries to raise awareness of several key social issues. At its most obvious level, The Tearoom allows gamers to experience aspects of the lives of homosexual men in a time and place where they were being particularly targeted and persecuted. As Webber (2017b: online) wrote about the game in The Guardian:

In the game, large icons clearly indicate when it is or isn’t appropriate to look towards the man at the other urinal. It’s like a subversion of the stealth genre, as this time you want to be seen (though not by the cops). Yang wrote on his blog] that this mechanic was difficult to design because – as he puts it – “decades of male heterosexual hegemony have trained gamers into thinking of ‘looking’ as a ‘free’ action, with few consequences or results”. Players who are used to works that pander to the straight male gaze may struggle to empathise with someone for whom a glance may be punished.

However, in placing the contemporary gamer in this historically setting and role, it also raises questions and emotions about the continued marginalization and persecution of gay men (and women) today. In particular, Yang states that he wanted to ‘make players feel anxious about what they’ve got to lose’ (Webber 2017b: online). Also, significantly, in the game penises are replaced by guns. This is a direct response to Twitch banning the streaming of Yang’s previous games, but more generally, it also highlights the absurdity that a video game industry, and society more widely, which happier to accept the depiction of a deadly weapon in a video game, than it is male genitalia. This game then, seeks to make important political points, and raise awareness of historical and contemporary social issues, by placing the gamer in a specific social setting and role; in the shoes of a gay man in 1960s Ohio.

Proof of video games’ effectiveness as mediated experiences of other perspectives can be found in testimonies of people who have been able to better understand a person’s situation thanks to playing them. According to Miechowski, the developer of This War of Mine, that would be the case of a woman who is the daughter of a war refugee. After playing the game, she declared that it helped her to understand her mother ‘and the horrors she went through during the war’. Although spatial, cultural, and emotional proximity can help in the process of empathizing with others, sometimes additional mediations are needed and video games are able to provide them. This hypothesis seems to be corroborated by the experimental study of Bachen et al. (2012) carried out in three Northern California high schools with 301 students, examining the effects of playing the video game Real Lives (Educational Simulations, 2010) – defined as an ‘interactive life simulation game that enables you to live one of billions of lives in any country in the world’ – on empathy. The study concluded that, even when there was geographical and cultural distance involved, those who played the video game experienced an increase in their ‘sense of global empathy’ and boosted ‘their interest in learning more about the countries in which their characters live’ (Bachen et al., 2012: 452). These kinds of video games allow players, Bogost (2007: 135) suggests, to ‘engage in political actions that many will never have previously experienced’, which, in the end, will probably ‘deepen their understanding of the multiple causal forces that affect any given, always unique, set of historical circumstances’.

These mediations can be so powerful that they are capable of unleashing strong emotional responses in players. Laura, a 26-year-old indie developer, narrates how specific individuals empathized with the characters in one of her video games, which is replete with difficult decisions to make, usually involving survival and violent scenarios, and the high probability of hurting other characters. Some players identify with the characters as human beings, ‘bloody hell, it’s a person!’ (Laura); this would explain some of the reactions to playing the video game, like a girl who was streaming her gameplay – in a playable section that depicts a long and explicit process of torture that your character and one of his companions have to endure – and started to cry:

And she got to the point in which she started to cry. It was like, ‘I can’t take more of this’, she was crying and very upset (Laura).

This is not an isolated example. For instance, Miechowski enumerates a list of intense emotional responses that were triggered by This War of Mine:

I know people depressed because they saw suffering in the game. I saw people excited, because they survived. I saw people having a sort of catharsis feeling when they survived, and I saw people being embarrassed or even had feelings of remorse, because of the evil deeds they had made in the virtual world.

Excitement, depression, embarrassment, remorse, and relief were some of the usual reactions amongst players of This War of Mine. This is linked to the developers’ decision to place a morale system into the game with different states: content, sad, depressed, and broken. This affects the characters’ performance and can be crucial to their survival. The morale status is affected by the decisions made, either negatively – by stealing from vulnerable individuals, hurting and killing other people, not helping your neighbours or people in need, being ill, wounded or hungry – or positively – by helping vulnerable people in distress, listening to music, sleeping comfortably, speaking to other survivors. This means that players’ actions have a direct impact on the characters they are controlling; which enhances the emotional and empathic reactions to the extent that there are some players who wish they could control a character with a lack of empathy:

The game is tough! I wish some of my characters were sociopaths/psychopaths. I mean fuck! Steal some food from an old couple causing them to starve to death, or kill someone who isn’t an armed thug, and they go into a huge depression and just become worthless! (John1912 in Oestreicher, 2015)

There is no doubt that video games connect players to other realities in a mediated way by using and provoking a sense of empathy.

[…]

Identification

Empathy and identification are, to a certain extent, interdependent concepts. There could hardly be empathy without a process of, at least partial, identification with the reality that is being shown to us; on the other hand, identifying with someone or something requires a sense of empathy, the possibility to recognize oneself in the other – human or not – and their tribulations. In accord with De Waal (2009: 80), it is reasonably safe to affirm that if ‘identification with others opens the door for empathy, the absence of identification closes that door’. In fact, when it comes to video games, the player has more chance to develop their empathy when this ‘not only takes the perspective of another, but also begins to identify with the character represented’ (Bachen et al., 2012: 440).

[…]

In her research on the relationship between identity, identification, and media representation among people who play video games and are members of marginalized groups, Adrianne Shaw (2014) draws a clear distinction between identifying with a video game character and identifying as a member of a group. This means that not everyone that shares a specific identifier such as gender, sexuality, race, and nationality with other individuals will automatically identify with a character or a situation that supposedly resembles or represents them. In fact, it is possible, and not uncommon, to hear individuals state that they identify with characters that are not necessarily like them. For instance, Shaw suggested that, even though the interviewees gave her different definitions of identification, the tying thread among them was ‘finding a connection with a character’ (Shaw, 2014: 69). This connection could range from a strong identification with the character, with whom they may share several social and personal characteristics and experiences, to recognizing some aspects of themselves in the character without clearly identifying with them; it could also take the shape of empathy or sympathy, including different shades of intellectual or emotional connections. Therefore, identification might be defined as ‘a process by which we come to feel an affective connection with a character on the basis of seeing that character as separate and yet a part of us in some way’ (Shaw, 2014: 94).

[…]

[We would like to understand identification] as a multifaceted connection between a player and a video game character or situation, which can entail different grades of involvement, empathy, and (self)recognition. […] The connections that are established between players and video games are diverse and promiscuous, and they are not necessarily based on previously shared identifiers of characteristics. After all, identification is conceptualized ‘as contextual, fluid, and imaginative’ (Shaw, 2014: 64); an open notion that invites researchers to ‘embrace the diversity of those experiences’ (Shaw, 2014: 70). In this case, identification is a sort of connection, a process by which it is possible to relate to other people, stories, situations, and realities. The key to this connection is not necessarily similarity (no matter how big or small), but rather, relatability:

Giving people other perspectives is good. I think that it is valuable by itself. Empathy, I think, will come if you try to make the characters relatable (Karla Zimonja).

In this case, making the characters of Gone Home relatable, does not make them inevitably equal or similar to someone in a specific social category or group. Resemblance, or likeness, is not the prerequisite for the connection (although it might be important in certain cases as we show above) to take place. Relatability alludes to the possibility (and easiness) of understanding someone or something, and by doing so, it facilitates the emergence of connections with those situations, even if these are completely alien to them. This opens the opportunity to give people other perspectives, without forcing them, even temporarily, to occupy those positions without question, resistance, or critical distance. Shaw summarizes this approach to perfection:

Identification, then, is not about a static, linear, measurable connection to a character. Rather, it is about seeing ourselves reflected in the world and relating to images of others (Shaw, 2014: 70-71).

In these processes of identification, an exclusive one-to-one connection with a character is rare and mainly not relevant. That would be like establishing a connection only based on a single correlation between a player and a character, as if the authors of this book could imagine they are Guybrush Threepwood while ignoring the remaining characters and the rich universe of situations, places, and adventures drawn in The Secret of Monkey Island (LucasArts, 1990). Dealing with the contrast between identification and disidentification (Muñoz, 1999; Staiger, 2005) processes, Shaw learnt from her research participants’ experiences that ‘we can enjoy texts that are in no way about us, just as we can feel excluded from texts that presume to be about us but fail to ring true to our experiences’ (Shaw, 2014: 78). In this regard, and after analyzing online comments relating to the game Gone Home, we are able to reach similar conclusions and highlight the intricacies of empathy and identification in video games. For instance, there are those – even amongst gay and lesbian players – who think Gone Home is a stereotyped, bland, and stigmatizing title, which only works for the self-indulgence of those who consider themselves trendy, progressive, and liberal:

As someone who the story should relate to (supposedly), it’s a rather poor portrayal. [...] If the idea was to portray (stigmatise) the overly dramatic people in our community who like to stick together, lavishing over their personal sappy stories as to how things were terrible for them and they have made it now (most of them stay stuck into that state), then mission accomplished. If it was to make some people feel better about themselves and comfort their own open-mindedness and liberalism by praising the subject, then mission accomplished there as well. (Muskatnuss in Polygon, 2013).

In contrast, there are others, both those who identify as gay or not, who consider Gone Home an appealing and laudable game. However, as the following comments highlight, simply having ‘queer’ elements (whatever they maybe) in a game is not necessarily going to make it more relatable or appealing:

Just to make a point, as a gay gamer myself, while I definitely did experience Gone Home and would recommended it, I don’t pick games just because they do or do not have gay content. I play games that appeal to me in general. If Gone Home had been a crappy game, then it’d still be a crappy game whether or not it had queer content in it. Just adding a gay element doesn’t automatically make it appeal to me (oxHanoverxo in Allen, 2014).

The process of identifying with a game, its characters, story, and universe is not automatic and does not necessarily rest on specific shared identifiers, since it is more of an emergence. As outlined in Chapter 4, video games are experiences, and experiences are there to be lived, felt, enjoyed, and suffered.

Therefore, the mediation that video games operate when connecting players to different circumstances has more to do with resonances of a set of experiences than the exact reproduction of particular vivid experiences.

[…]

In the end, we identify with not just one aspect of a video game, but rather with its complexities, and what is articulated in and around it: the story, the characters, the universe, the events, the actions, the mechanics, reviews, other players’ experiences (accessed on offline and online accounts), and so forth.

It is also important to bear in mind, that a video game is also rarely a set and self-contained text. Not only do video games change as we interact with them, but they are frequently updated or patched by games developers. Moreover, our understanding and opinions of a game, and our identification with (elements of) it (or not), will be influenced by a whole range of para-textual elements, such as advertising, game reviews, others opinions and interpretations, and much more beyond. How we identify with a game, and what we identify with, is far from straightforward.

[…]

This complex relationship is something that the developers of Life is Strange (Dontnod, 2015) took seriously when they tried to address a particularly difficult situation, that of bullying (and its potential terrible consequences). Mikel Koch, one of its co-directors, talked in an interview about the particular storyline where they approach the problems of a girl, who is being bullied and harassed, including cyber-bullying, by her schoolmates, and how they had to be ‘careful as designers and writers to be sure that the player is connected to the characters’, so they felt obliged to ‘develop the right relationship between Max [the character controlled by the player], the player and her [the bullied woman]’ (Skrebels, 2016).

We see that empathy and identification processes are mainly describing experiences that are through video games, connecting us to the reality that surrounds us. Instead of the immersive, absorbing experiences of those who play video games as a form of escapism, we see how video games are also capable of other kinds of mediations: they transform our everyday life experiences in ways that multiply, instead of severing, our links to society.

The limits of video games as mediators of experience

Despite being powerful devices that make unexpected associations with the most varied agents, video games show also significant limitations when it comes to fostering processes of empathy and identification. In fact, the idea of video games as a medium for developing empathic responses, including the aforementioned label of empathy games, has drawn fierce criticism from some individuals. This is the case of Anna Anthropy, a game developer that, among many other works, created the video game dys4ia (Anthropy, 2012), in which she tried to convey part of her experience as a trans woman and the process of undergoing a hormone replacement therapy. The game was widely praised, still is, as a video game that can help people to put themselves in the shoes of transgender people. However, this conceptualization of the game was sharply contested by Anthropy (2015) in a post on her website, where she strongly criticizes the notion of empathy games:

Empathy Game is about the farce of using a game as a substitute for education, as a way to claim allyship. You could spend hours pacing in a pair of beaten-up size thirteen heels to gain a point or two – a few people did – and still know nothing about the experience of being a trans woman, about how to be an ally to them. Being an ally takes work, it requires you to examine your own behavior, it is an ongoing process with no end point. That people are eager to use games as a shortcut to that, and way to feel like they've done the work and excuse themselves from further educating themselves, angers and disgusts me. You don't know what it's like to be me.

She considers that video games are capable of ‘communicating meaningful information and experiences’ (Anthropy, 2015), but they cannot ever fully replicate the complexities and nuances of other people’s experiences, especially of those who occupy a marginalized position. She particularly despises how the empathy game label has been mostly used and nurtured by ‘the ones with the most privilege and the least amount of willingness to improve themselves’ (Anthropy, 2015). The luring appeal of ‘playing as the other’ (Shaw, 2014: 176) implies the risk of cultural and political appropriation (Nakamura, 2002) that is far from a trigger for empathetic behaviours. In particular, parallels can be drawn here to the critique of sports video games made by David J. Leonard (2004). Here, Leonard argues, though sports video games, such as those in the EA Sports’ hugely popular NBA Live (1994-2009; 2013 to date) and Madden NFL (EA Sports, 1988 to date) series, frequently allow (predominantly) white gamers to play the role of black sports stars, this does nothing to ‘unsettle dominant notions’ or ‘break down barriers’, but rather they reinforce dominant stereotypes of Black athleticism, and allows the (white) gamer to put on ‘Blackface’.

Hence, there even could be cases in which video games go beyond empathetic inefficacy or appropriations from dominant and privileged sectors of society, and have other unforeseen negative consequences. In an article at The Guardian, Simon Parkin (2016) points to the example of Spent (McKinney, 2011), a free online video game on surviving poverty and homelessness in the context of the United States. The game aims to make players understand the people who live in poverty in order to generate a current of empathy towards those in need. Nevertheless, Psychology Today (Roussos, 2015) carried out a study that suggested that many individuals who played the game were not affected by it and, furthermore, there were some participants on whom it had a negative effect (including some players who were sympathetic to the poor beforehand). It seems that the problem rests with ‘game’s mechanics, which leave players with the impression that people living in poverty are able to change their circumstances simply by changing their choices’ (Parkin, 2016). Certainly, parallels could be drawn here to the arguments we set out in Chapter 3, which highlights video games as an exemplar of neoliberal culture par excellence. Video games have a tendency to quantify the unquantifiable and turn complex social situations into simple rational choices. For example, buying alcohol instead of food may not appear to be the most rational of choices for someone living in poverty, but for that individual it may be an addiction, or a way to dull the pain of their situation, or even the only pleasure they get in their limited lives. What it really feels like to live on the breadline can never be communicated in a video game, and to turn this into simple rational choices massively oversimplifies complex and multifaceted situations. Parkin therefore reaches the conclusion that although games can ‘create empathy and deepen our understanding of social systems’, they also ‘enforce problematic values in profound ways’. In a similar vein, Gorry (2009: 11) is worried about how digital culture ‘exposes us to the pain and suffering of so many others, it might also numb our emotions, distance us from our fellow humans, and attenuate our empathetic responses to their misfortunes’ and he adds that in ‘our life on the screen, we might know more and more about others and care less and less about them’. This could be described as a dissonant empathy process by which video games, far from connecting us with other realities, are estranging us from them even more.

Similarly, other cases point to the difficulties, if not impossibility, of transmitting an experience. This is perfectly visible in one of the campaigns that UNICEF launched in 2014 to raise awareness of the situation of children in South Sudan. They sent an actor to simulate a pitch for a new video game in front of an audience of video gamers, developers, and video game journalists that thought the pitch was real at the Video Gamers United convention in Washington DC. The game is entitled Elika’s Escape and players control a seven-year-old girl – Elika – in extreme war time situations. The aim is to make her and her little brother survive in those particular life-threatening conditions. Elika’s Escape supposedly starts with Elika’s mother dying of cholera, her big brother being killed for defending her from attackers, and she fleeing home with her baby brother. At that point, the pitchman enthusiastically shouts ‘we are taking the level of horror in this game even to infants! Are you guys with me?’ The reaction of spectators is that of notable discomfort, nothing is left of the initial enthusiasm before they knew what the video game was about. The presenter continues relating Erika’s story: now the player reaches a refugee camp without food and the most elemental sanitary conditions. In order to survive and save her baby brother, Elika, the player, must decide whether to submit to prostitution to get the money they need. That is when several attendees walk out of the room, disgusted with what they are witnessing. After this, the pitchman passes the microphone to Mari Malek, a South Sudanese refugee, on whose life Elika’s Escape is based: ‘This is not a game. Elika’s story is true, she is me and she is so many of the South Sudanese children that are going through this experience at this moment’. In UNICEF’s promotional video, they assert that ‘What is too much for a video game is happening daily to children in South Sudan’. This shows the untranslatability of certain experiences, evincing the limits and great difficulties of the medium when it comes to communicating and expressing those extreme realities in order to create game experiences grounded on them.

All of this demonstrates that the relationship that players can have with video games, their rich universes, and reality is complex and, even if they have the potential to foster empathic responses, it is not a connection that is established easily. No matter how close or far we are from the circumstances depicted in those video games, how complex or simple the situations reproduced in the video game are, or even if there are aspects of the experience that are, by definition, irrepresentable, we will experience different grades of connection with them (or none) depending on the processes that facilitate or impede the (dis)associations.

[…]

Conclusions

In this chapter, we have seen how video games are not just about ‘escapism’, rather, we have been able to demonstrate that video games are also mediation devices that allow us to experience situations that we have never had or would not have otherwise. This presents the opportunity of encouraging empathy and identification processes amongst players, and as a way to connect with circumstances and people whether they are familiar or alien to us. Video games not only work as sophisticated instruments for escapism, but can also open multiple paths towards other aspects of reality that can help us to (re)connect with it in unforeseen ways.

Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind these are game experiences that, may, convey some aspects of those experiences that they are recreating, representing, simulating, or re-enacting, and they are not the experience themselves. […]. The relationship with the player and those realities expressed in a video game is therefore not defined in terms of correspondence but of connection, emergence, or enactment. Video games are a bundled hinterland of experiences.

References

Alexander, Leigh (2011). “Interview: Making Faces with Team Bondi’s McNamara, L.A. Noire”, Gamasutra, http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/123427/Interview_Making_Faces_With_Team_Bondis_McNamara_LA_Noire.php [Last accessed: 11/01/2017].

Allen, Samantha (2014). “Closing the gap between queer and mainstream games”, Polygon, http://www.polygon.com/2014/4/2/5549878/closing-the-gap-between-queer-and-mainstream-games [Last accessed: 07/01/2017]

Anthropy, Anna (2015). “Empathy Game”, Auntiepixelante, http://auntiepixelante.com/empathygame/ [Last accessed: 04/01/2017]

Appelbaum, Mark; Calvert, Sandra; Dodge, Kenneth; Graham, Sandra; Hall, Gordon N.; Hamby, Sherry; Hedges, Lawrence (2015). Technical Report on the Review of the Violent Video Game Literature. Washington: APA Task Force on Violent Media, http://www.apa.org/pi/families/review-video-games.pdf

Bachen, Christine M.; Hernández-Ramos, Pedro F.; Raphael, Chad (2012). “Simulating REAL LIVES: Promoting Global Empathy and Interest in Learning Through Simulation Games”, Simulation & Gaming, 43, 4: 437-460.

Bogost, Ian. (2007). Persuasive Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Butler, Judith (1999). Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge, 2nd edition.

Calleja, Gordon (2010). “Digital Games and Escapism”, Games and Culture, 5 (4): 335-353.

Castronova, Edward (2005). Synthetic Worlds: The Business & Culture of Online Games. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Centola, Damon; González-Avella, Juan Carlos; Eguíluz, Víctor M.; San Miguel, Maxi (2007). “Homophily, Cultural Drift, and the Co-Evolution of Cultural Groups”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51, 6: 905-929.

Copier, Marinka (2007). Beyond the magic circle: A network perspective on role-play online games. PhD dissertation, Utrecht University.

Crawford, Garry (2012). Video Gamers. London: Routledge.

Davis, Mark H. (1996). Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach. New York: Avalon Publishing.

De Waal, Frans (2009). The Age of Empathy: Nature's Lessons for a Kinder Society. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Dean, Carolyn (2004). The fragility of empathy after the Holocaust. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Evans, Andrew (2001). This virtual life: Escapism in the media. London: Vision.

Gorry, Anthony (2009). “Empathy in the virtual world”, Chronicle of Higher Education, 56: 10-12.

Hall, Stuart (1996). “Who needs identity?” in Hall, Stuart and Du Gay, Paul, Questions of Cultural Identity. London: SAGE, 1-17.

Haraway, Donna (1991). Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

Harris, Barbara; Shattell, Mona; Rusch, Doris C.; Zefeldt, Mary J. (2015). “Barriers to Learning about Mental Illness through Empathy Games – Results of a User Study on Perfection”, Well Playerd, 4, 2: 56-75.

Huizinga, Johan (1949). Homo Ludens. A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Taylor and Francis.

Humphreys, Laud (1970). The Tearoom Trade: interpersonal sex in public places. London: Duckworth Overlook

Juul, Jesper (2008). “The Magic Circle and the Puzzle Piece”, Philosophy of Computers Games, Conference proceedings, https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/2554 [Last accessed: 26/04/2017].

Klimmt, Christoph; Hefner, Dorothée; Vorderer, Peter (2009). “The Video Game Experience as ‘True’ Identification:A Theory of Enjoyable Alterations of Players’ Self-Perception”, Communication Theory, 19: 351-373.

Kossinets, Gueorgi and Watts, Duncan J. (2009). “Origins of Homophily in an Evolving Social Network”, American Journal of Sociology, 115, 2: 405-450.

Leonard, D. (2004) ‘High Tech Blackface – Race, Sports Video Games and Becoming the Other’, Intelligent Agent, 4 (2). Online at: http://www.intelligentagent.com/archive/Vol4_No4_gaming_leonard.htm

MacCannell, Dean (1973). “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings”, American Journal of Sociology, 73:3: 589-603.

Madigan, Jamie (2012). “The Walking Dead, Mirror Neurons, and Empathy”, The Psychology of Video Games, November 7, retrieved at http://www.psychologyofgames.com/2012/11/the-walking-dead-mirror-neurons-and-empathy/ [last accessed: 8 September 2016].

McPherson, Miller; Smith-Lovin, Lynn; Cook, James M. (2001). “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks”, Annual Review of Sociology, 27: 415-444.

Muñoz, José Esteban (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performanve of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nakamura, Lisa (2002). Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. New York: Routledge.

Oestreicher, Jason (2014). “Quick Look: This War of Mine”, GiantBomb, http://www.giantbomb.com/videos/quick-look-this-war-of-mine/2300-9724/ [Last accessed: 11/01/2017]

Pargman, Daniel and Jakobsson, Peter (2008). “Do you believe in magic? Computer games in everyday life�”, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 11, 2: 225-244

Parkin, Simon (2016). “Video games are a powerful tool which must be wielded with care”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/apr/03/games-social-issues-who-cares-wins [Last accessed: 04/01/2017]

Pine, Joseph B. and Gilmore, James H. (2011). The Experience Economy. Updated Edition. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Polygon (2013). “Looking back: Gone Home”, Polygon, http://www.polygon.com/features/2013/12/25/5241552/looking-back-gone-home [Last accessed: 07/01/2017]

Poremba, Cindy (2013). “Performative Inquiry and the Sublime in Escape from Woomera”, Games and Culture, 8, 5: 354-367

Rifkin, Jeremy (2010). The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Roussos, Gina (2015). “When Good Intentions Go Awry. The counterintutitive effects of a prosocial online game”, Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/sound-science-sound-policy/201512/when-good-intentions-go-awry [Last accessed: 04/01/2017].

Salen, Katie and Zimmerman, Eric (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Scutti, Susan (2016). “Do video games lead to violence?”, CNN, http://edition.cnn.com/2016/07/25/health/video-games-and-violence/ [Last accessed: 11/01/2017]

Shaw, Adrienne (2014). Gaming at the Edge. Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Simkins, David W. and Steinkuehler, Constance (2008). “Critical ethical reasoning and role-play”, Games and Culture, 3, 3-4: 333-355.

Skrebels, Joe (2016). “Directors Commentary - revisiting Life is Strange with its creators”, Gamesradar+, http://www.gamesradar.com/life-is-strange-interview-directors/ [Last accessed: 03/01/2017].

Smethurst, Toby and Craps, Stef (2015). “Playing with Trauma: Interreactivity, Empathy, and Complicity in The Walking Dead Video Game”, Games and Culture, 10, 3: 269-290.

Staiger, Janet (2005). Media Reception Studies. New York: New York University Press.

Taylor, T. L. (2007). “Pushing the Borders: Player Participation and Game Culture”, In Karaganis, Joe. (editor). Structures of Participation in Digital Culture. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.112–132.

Titchener, Edward (1909). Lectures on the Experimental Psychology of the Thought-processes. London: Macmillan

Tuan, Yi-Fu (1998). Escapism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Webber, Jordan Erica (2017a). “Learning morality through gaming”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/aug/13/learning-morality-through-gaming

Webber, Jordan Erica (2017b). ‘The Tearoom: the gay cruising game challenging industry norms’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/11/the-tearoom-game-gay-cruising-1960s-industry-norms-robert-yang [Last accessed 14/08/2017].

Webber, Jordan Erica and Griliopoulos, Daniel (2017). Ten Things Video Games Can Teach Us. London: Robinson.

Yang, Robert (2017). “The Tearoom as Risky Business”, Radiator Design Blog. http://www.blog.radiator.debacle.us/2017/06/the-tearoom-as-record-of-risky-business.html [Last accessed 16/08/2017]

[i] http://edition.cnn.com/specials/middleeast/syrian-refugees/

[ii] http://www.blog.radiator.debacle.us/2017/06/the-tearoom-as-record-of-risky-business.html

[iii] Definition extracted from Educational Simulations website: http://www.educationalsimulations.com/

[iv] She is making reference to the interactive art exhibit at Babycastles (http://babycastles.com/event/babycastles_presents_anna_anthropy_presents_the_road_to_empathy) that featured a pair of old used boots that belonged to Anthropy, a pedometer, and a chalkboard. Visitors were encouraged to walk along in her shoes, measure the distance walked with the pedometer and then register their score on the chalkboard (one point per mile). The installation was the product of the ironic response she gave to someone who asked her permission to exhibit dys4ria as a way to show how video games could ‘make us empathize with others by letting us walk a mile in their shoes’ (Anthropy, 2015).

[v] http://playspent.org/html/

[vi] https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/southsudan_78090.html

[vii] The pitch was recorded to register the audience reactions and to use the video for their campaign. The video can be accessed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iN6Wc-9r3l4

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like