Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

For years the Dutch game industry was labeled a 'top sector'. A recent report shows that economic development has been stagnant for the last 4 years and that there exists an excess on the labor market. On the role of platforms and misguided perceptions.

The evident state of the Dutch games industry is still sinking in, even after I’ve had a few days to think about the news that came out last week. The statistics came from the Dutch Games Association (DGA) in its second installment of the Games Monitor, a report profiling the economic development of the Dutch game industry from 2011 to 2015. The Dutch game industry ― encompassing development, production, publishing, and activities related to the commercialization of digital games ― is one of nine industries labelled ’Top Sectors‘ by the Dutch government. The Games Monitor documents some surprising trends that raise important questions. First, there is a sizeable discrepancy between the number of graduates coming out of degree programs for the gaming industry and the size of the labor market. Second, the report shows signs of stagnation for key indicators of economic growth in the sector. Combined, these findings suggest a difficulty to adapt to industry shifts. Whereas the global game industry is growing at double-digit rates, the Dutch market is lagging behind. What is driving these trends? And, what potential policies are there for regaining growth?

The evident state of the Dutch games industry is still sinking in, even after I’ve had a few days to think about the news that came out last week. The statistics came from the Dutch Games Association (DGA) in its second installment of the Games Monitor, a report profiling the economic development of the Dutch game industry from 2011 to 2015. The Dutch game industry ― encompassing development, production, publishing, and activities related to the commercialization of digital games ― is one of nine industries labelled ’Top Sectors‘ by the Dutch government. The Games Monitor documents some surprising trends that raise important questions. First, there is a sizeable discrepancy between the number of graduates coming out of degree programs for the gaming industry and the size of the labor market. Second, the report shows signs of stagnation for key indicators of economic growth in the sector. Combined, these findings suggest a difficulty to adapt to industry shifts. Whereas the global game industry is growing at double-digit rates, the Dutch market is lagging behind. What is driving these trends? And, what potential policies are there for regaining growth?

The State of the Dutch Game Industry

In 2015 there were 3,030 full time employees (FTE) in the Dutch video game industry, employed by 455 firms. Estimated revenues for these firms totaled somewhere between €155 and €225 million. The number of firms is up 42% from 320 in 2011, but revenues and the size of the labor market have been stagnant since 2012 (the year the first Games Monitor was published). Further signs of stagnation can be found in the number of firms that have gone out of business: 110 since 2011. In other words, 245 new firms were founded in the period between 2012 and 2015. Since the size of the labor market remained stable, the majority of these firms encompass small teams and individuals. Indeed, the average company size decreased from 9 FTE in 2011 to 7 FTE in 2015. Notably, these averages are positively skewed by a few large companies such as Guerrilla Games and Vanguard Entertainment.

This lack of growth coincides with a stark uptake in the number of dedicated video game degree programs and the subsequent outflow of graduates. In 2015 there were 44 dedicated video game degree programs across three educational levels (i.e. 22 vocational programs, 17 vocational college-taught programs, and 5 university programs). Collectively, these programs produce 991 graduates. The report notes that approximately 258 graduates won’t seek employment because they will take up additional training in higher or more specialized degree programs. Nevertheless, 733 potential jobseekers in a labor force of 3,030 corresponds with an anticipated growth of 24% in an industry that otherwise displays signals of stagnation and decline. Adding insult to injury is the fact that a portion of these degree programs started educating students only recently and the pool of graduates thus is expected to keep growing.

The Role of Digital Platforms

There are a number of causes for the mismatch between education and market development. There are two causes I think are salient: 1) the role of digital platforms the majority of games are released on, and2) the implications of the hit-driven market dynamic in these platforms.

Many, if not most, of the games produced in the Dutch video game industry are launched internationally on digital content platforms such as Apple’s iOS, Google’s Android, and Valve’s Steam. These platforms facilitate marketplaces where vast numbers of consumers choose from an impressive pool of games. For example, there are over half a billion users on Apple’s iPhone platform and there are close to 500,000 active games on Apple’s App Store worldwide. Game developers can enter these platforms with few or no restrictions, and the lack of tangible information carriers, such as CDs or cartridges, significantly reduces production costs compared to the old ways of distributing content. What’s more, search engines and online recommender systems have made it a lot easier for globally dispersed consumers to find content that truly fits their tastes. Theoretically, this creates a more level playing field for small producers of niche content.

While the arrival of new platforms suggest viable business opportunities, the state of the Dutch market implies that more is at play. Platform owners, for one, sometimes tend to implement policies that are to the detriment of game developers, particularly the small ones. For example, in 2012, Facebook removed most newsfeed notifications generated by social games. This policy stripped games like Farmville from their core growth mechanism, causing even the most successful game publishers to see a significant drop in revenue. Similarly, in December 2014, Apple implemented a policy by which European App Store consumers can get a 14 days no-questions-asked refund on any app related purchase. This raises the question: Why do platforms implement policies that can be such destroyers of firm value?

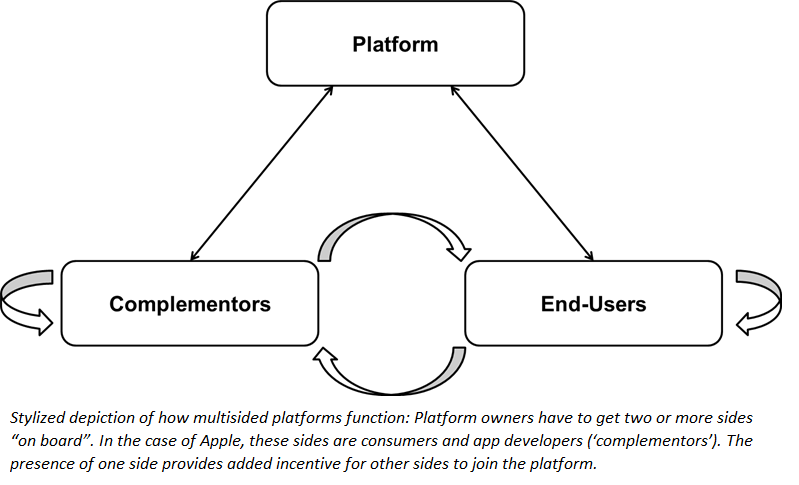

Platforms generate income from several ‘sides’ (e.g. end-users, app developers, and advertisers). And more often than not, one side accounts for the bulk of income for the platform. Other sides primarily serve as a means to attract more valuable customers. Indeed, multisided platforms have what is called ‘money sides’ and ‘subsidy sides’. In Apple’s case, consumers are clearly the money side; a profit is made on every i-device that Apple sells. On the other hand, Apple derives the substantial part of its income from only a tiny fraction of games launched on its platform (more about this below). Facebook, too, derives only a fraction of its income from social games on its Facebook Platform; approximately 3% in 2015.

Naturally, platform owners implement governance policies that benefit the most lucrative side on their platform, but may end up hurting the other sides. It’s clear to see how this point could be lost on Dutch game developers ‒ and those from other countries too. Consumers of traditional home video game consoles such as PlayStation or Xbox were the subsidy side, whereas game developers were the money side. Game developers, therefore, faced substantially more prosperous competitive conditions than they currently do on digital platforms.

Hits-driven Business

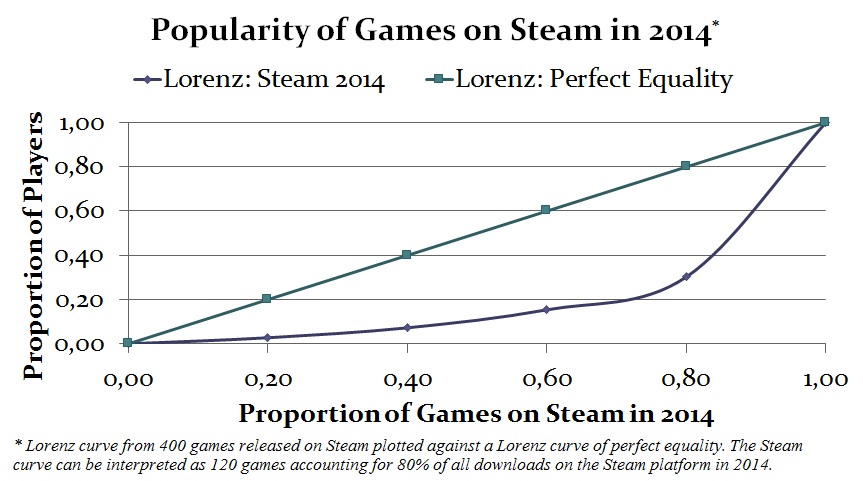

If we look at the competition among game developers we find further evidence for why so many fail to generate revenue. Like many other entertainment properties, games are a hit-driven business. And while this is nothing new, video games have been a hits-driven business since the early 1980s, the implications for game developers are amplified in the context of digital content platforms. That is to say, sales distributions in markets for entertainment goods typically follow the Pareto principle: a small share of the goods (e.g. 20%) accounts for a disproportionally large share of sales (e.g. 80%). Although it was initially believed that the distribution of sales would be more equal on digital platforms, the opposite appears to be true. Facilitated by lower entry barriers and zero marginal production costs, digital platforms now enjoy a supply glut of games that come mostly from small developers.

Overwhelmed by the abundance of choice and huge variance in quality, consumers tend to rely on a range of quality signals to guide their selection. These signals include games’ sales ranking, ‘star feature’ placement on the platforms’ storefront, and big marketing campaigns. The result is a growing discrepancy in sales between the ’head’ and the ’tail’ of the market. My own research shows that this is true even for a relatively underpopulated platform like Steam. Games launched on Steam in 2014 have a Gini coefficient of 0.58. This is a standard measure to express income inequality. The number indicates that players are less equally distributed across games than income in any OECD country to date! To compete with a top ranked game such as Clash of Clans would require deep pockets full of marketing budget and close relationships with platform owners. Add to this the platforms’ liberal pricing policies for content creators (another governance policy that favors the consumer), which have led to over 75 per cent of the games now being either free or free to play, and we start to see why small Dutch game developers struggle to make ends meet.

Notwithstanding these dynamics, every now and then a game from an unknown game developer does rise to the top of the ranks. Dutch games like Ridiculous Fishing (Vlambeer; opening image) and Sky Chasers (Luck Kat Studios) are exemplars of what many game developers want these marketplaces to be: platforms where users consume content with real quality from independent firms rather than mediocre but licensed content from incumbent marketing machines.

Alas, a recent market report shows that the top ten bestselling games on many digital distribution platforms comes increasingly from incumbent publishers with licensed content, big marketing budgets, and longstanding relationships with major platform owners. An era of consolidation, akin to the home video game console industry in the 1990s but this time without a cap on market entry, has been set in motion. For every top ten game by a small game developer there are now hundreds of thousands of games that neither generate revenues nor recoup costs.

I would contend that at the core of the Dutch problem are aspiring game developers that don’t realise the odds are stacked against them. They either ignore or don’t see the many commercial failures and are blinded by the very visible but relatively few successes in the marketplace. It’s also very unlikely that undergraduates on video game degree programmes are aware of the dynamics mentioned here. It seems that many educational programme directors have tapped into students’ upward perceptional biases by offering degree programmes that promise the necessary skills to kickstart a career in games. However, after graduating, eager students are faced with becoming part of an excess on the labor market and most fail to find employment with incumbent studios. Rather than leaving the industry, many go on to found their own firms of small teams, to release niche content on digital distribution platforms. And as the data make painfully clear, usually with little or no success. What we have here is a vicious cycle that is poised to repeat itself without any change in strategic direction.

What Can be Done?

While part of my analysis here is also characteristic of other geographical sectors of the game industry and to the entertainment industries in general, there are some changes that the Dutch market in particular could implement to prevent it from further failure. Here are my recommendations for those who offer video game degrees, for game producers, and for government policy officers:

Advice for knowledge institutions

Redesign the curriculum and include business courses. Anticipate the fact that many graduates will have to become entrepreneurs by including courses in entrepreneurship, industry analysis, entertainment marketing and digital economics, amongst other gaming-industry specific business courses. They should be updated annually (with input from industry actors) given the rapidly changing business environment;

Develop international internship and placement offices. The oversupply of graduates and the high quality of education in the Netherlands means there should be more efforts to develop international internships and placements. Students should be motivated and helped to look for professional experience and employment opportunities in other countries;

Stronger selection at the gate. An annual cap on enrolment numbers not only improves the quality of education any individual student is likely to receive, it also allows for stronger screening and selection strategies of students, raising the quality of admissions and in due course, raising the reputation of the program.

Advice for small game developers

Pursue ‘blockbuster strategies’ for niche content. Quality prevails ‒ but not without sufficient marketing efforts. Why not exclusively commercialize content for which there is a good fit with both the technological functionality of the platform and the demographics of its installed base. Heavily invest in promotion, marketing and in developing relationships with the platform owner;

Form alliances with firms that possess complementary skills. My own research shows that when studios lack marketing skills or relationships with platform owners, they are better off if they partner with firms that have such skills, and even if these firms typically demand a share of proceeds, it’s justified if partners can augment the overall inflow of revenues. Remember, it’s not just about the share of the pie, it’s also about the size of the pie;

Recruit interns with a long-term perspective. Interns are cheap and plentiful in the Netherlands. Yet they become expensive if they are replaced every six months; they become a knowledge drain and can steal ideas, not to mention the dampening effect on the moral of other employees. So only recruit interns if you want them to work at your firm beyond the internship.

Advice for government policy officers

Re-evaluate the allocation of subsidies. Subsidies should benefit the many (e.g. tax breaks, start-up hubs, financial support for trade association) to foster talent and creativity. Yet, subsidies should also benefit the few that have greatest potential and a proven track record of launching blockbuster games. In the end, a few real hits will generate positive spillover effects to the entire market;

Consider tighter regulation of degree programs. Potential policies include: a) regulation of program designs to include business courses; b) enforcing universities to issue disclaimers about employment prospects; c) regulation of the number of programs and/or students admitted each academic year (e.g. via subsidies or taxes);

Consider further regulation of digital platforms. While I am largely in favor of deregulation of most markets, European policymakers could further expand their ‘digital agenda’ to include policies that not only benefit consumers but also benefit small content producers on digital platforms.

This is a re-post from my Strategy Guide blog.

I benefited from comments provided by two industry experts: David Nieborg and Niels ‘t Hooft.

Download DGA’s Games Monitor 2015.

A short version of this article was posted on RSM Discovery

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like