With Facebook-based online games from third parties sporting millions of unique monthly players, Gamasutra sits down with Gareth Davis, Facebook's platform manager, to discuss the social network, the rolling out of Facebook's own payment platform, and more.

The potential for Facebook to be a massive platform for game development seems difficult to understate as of mid-2009. Already, it's host to a huge number of games, several of which pull in millions of users on a regular basis.

In fact, several game on Facebook have surpassed World of Warcraft's subscriber base in terms of monthly unique players, as recent charts have shown. Of course, none of the social network-based MMOs charge $15 a month to play -- and many of the players never buy virtual items, which monetize these games. But many do, as the landscape rapidly evolves, and it's becoming clear that you can build userbase for online games incredibly fast using social networks.

It's been just over two years since Facebook was opened up as a platform to application developers. Companies have been founded, have released games, have become profitable, and most recently, have begun to hire talent from the mainstream development of console and PC packaged software.

What does the future hold? What does the platform offer? Gamasutra decided that the best person to answer this question is Gareth Davis, Facebook's platform manager.

We first encountered Davis at the recent Social Games Summit, where he spoke on a panel about social gaming from Facebook's perspective. He promised more than we can currently imagine for the future of Facebook Connect's Xbox 360 and Nintendo DSi integration, and talked about the stability and appeal of the platform and its 200 million-plus users, approximately half of whom access the site each day.

Here, Davis expands on those points and answers Gamasutra's questions about the present and future of Facebook and games, in an extensive interview conducted this month at Facebook's Palo Alto, California headquarters.

I've heard you have a background in the game industry. Can you elaborate?

Gareth Davis: Right. So, I worked for many years in the game industry, primarily as a game producer. I also did some work as a game designer and a game programmer. I had the privilege of working with a number of game developers and publishers, including Sega and Electronic Arts. My last position in that industry was as a game producer in the Maxis studio working on The Sims.

The feeling that I get is that when Facebook started having apps available, there wasn't this anticipation that games were going to be such a large part of the success of the apps. Was that a surprise?

GD: I think we knew that when we opened that platform, there would be many different kinds of applications. I think "surprise" is too strong a word. I think we're excited that games have become such... I think they're the largest category of apps on Facebook today, and have very high engagement levels.

People love to play them, and they're having a great time doing it. I mean, our gaming audience is in the tens of millions. And that's something that we're seeing, this kind of emergent behavior on the platform that we're really interested and excited by.

When you say "our gaming audience", do you feel that the majority of users on Facebook are a potential gaming audience or are an engaged gaming audience? Or do you feel like there are audience questions in terms of who is and who's not interested in that segment?

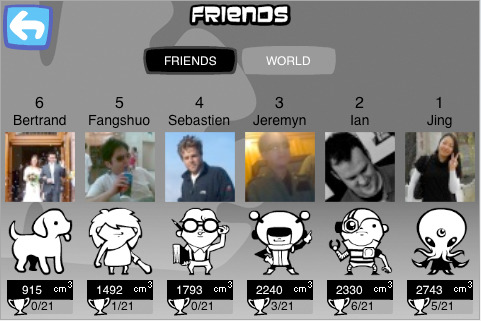

GD: I think that everyone is interested in playing games. Today, 70 percent of our users use applications, and the largest application category is games. And if you look at the top ten apps on Facebook, many of them are games. By monthly active, certainly. You understand monthly and daily, how we think about them? So, monthly is audience, it's kind of the size and scale of the app, and then daily is engagement. If you rank the dailies, the top few tend to be games.

Pet Society

What defines a game in the context of Facebook? It's a little bit different, right? Some things are very overtly games in the way that traditional console/PC games are games. Pet Society has very obvious game-y overtones, while something like Friends for Sale has a gamey-ness, but it's not exactly the same. It's not the trappings necessarily. Do you think about that? Or do you just leave that up to the developers?

GD: Yeah, it's really up to the developers. I think what we're seeing on Facebook is a new audience. We have 200 million monthly active users and tens of millions playing games every month. I think that breaks out into a few different groups or categories. You have people that love to play games and play games on other platforms and are playing games on Facebook.

And I think you have a large category of people who want to spend time with their friends, they're spending time on Facebook, and a game is a wonderful way for them to interact with their friends and family and spend time together, interact. So that's kind of what people are doing on Facebook.

In terms of what is a game and what isn't, I think that's really up to developers and users. And I think we have many people today on Facebook that are playing games that don't identify themselves as gamers and wouldn't consider themselves playing games, when in fact they are.

I think the classic definition of gaming is as kind of an environment or a set of rules that we can interact and have fun with, and if you think about it at that abstract level, many of the applications on Facebook are either clearly games or have game-like aspects to them.

We often get the question, "Is Facebook a game?" I think there are many elements in Facebook that are game-like in behavior that make it so compelling and why we have 50 percent of our audience come back every single day. So, over a hundred million users every single day, and they're coming back to hang out with their friends and engage with them.

Something that I've been mindful of as I've been discussing social games and social networking, this is moving very quickly and is a lot younger than we almost think it is, because it's slotted in so emphatically into our lives very quickly. Obviously, Facebook has been around for several years, but this really is a phenomenon.

GD: We opened our platform up in the spring of 2007. I believe it was May, so we just passed our second birthday of the platform. And that really was the genesis and catalyst of an ecosystem showing up and building applications for Facebook.

What's really interesting to me is we have this thriving ecosystem of building apps on Facebook.com today, but also this shift towards social experiences that are off of Facebook.com using Connect technology.

And I talked a fair bit about this at the conference, but we're starting to see, for instance, like PopCap just released a game called Zuma. It's a traditional game of theirs on their website that Facebook can connect into, and suddenly, you get a social leadership board, and you publish your scores back to Facebook. And so we're seeing the use of those, the Facebook social graph, and the ability to publish stories really driving usage of that traditional casual game.

Zuma's been around for years.

GD: Right, but now lots of people here are playing it when they weren't playing it before because it's now a social game.

I certainly want to talk about Facebook Connect. I think there's a lot of stuff to talk about there, and I know you're a big proponent of it. First of all, where did the idea come from, opening up Facebook and creating an API that allows other things that are not Facebook to talk to Facebook?

GD: So, this is the original platform?

I mean Facebook in terms of Facebook Connect.

GD: The two are actually related. It's an interesting story. By 2007, we had been around for a few years, and we had a good many users. We had built some of our own apps like Events, Notes, Links, Photos. And these apps, people were using them and were heavily engaged in them and really excited about them.

As we thought about what other apps we might want to build, we kind of realized two things. The first of that is there would be a tremendous range of ideas, some incredible ideas of how to use Facebook technologies in ways that we couldn't even imagine, and I think games was one of them. We didn't build a Facebook game. And the minute we opened the platform up, there were a lot of games available on the platform.

And the second is that even if we did have lots of great ideas, we would never have all the resources necessary to build them. So, by opening up the platform, it would allow anybody in the world to come up with great ideas, and then build them themselves, and let everyone benefit from them. So, that was the motivation behind our platform.

Then, in terms of Connect, the vision has always been that social experiences would be prevalent everywhere, on every device, on every website. And Facebook Connect was all about taking what was happening on Facebook.com, which we had now demonstrated people's interest and engagement and passion for, and opening that everywhere. So, it's kind of the same thinking behind the opening of the platform, was opening up Facebook to the world.

Who Has the Biggest Brain?

I think that I wasn't fully aware of what was going on with Facebook Connect until E3. And I don't know if that's just because I haven't been paying attention or because that was sort of where it became really obvious that it was going to touch on platforms that I hadn't anticipated. Obviously, it has, with the announcements of the Nintendo DSi and the Xbox 360. I did not anticipate that going into E3. Why is that important to touch those platforms?

GD: So, we believe that the incredible social activity that's happening on Facebook.com today will happen everywhere in the future, will happen on the web, on desktop applications, on mobile phones, on set top boxes, on game consoles, will happen everywhere. The compelling functionality and applications of Facebook have much broader applications than just one web site.

So, we've always had that vision. When you look at the gaming consoles, not only are they very popular, but they have a thriving development community that is building really interesting experiences. And we had spoken to a lot of game developers who were building games, not just for Facebook but for consoles. And they were really interested in building social experiences on the consoles and then furthermore connecting those experiences to Facebook and to other devices.

So, this concept of multi-device gaming that we're talking about now, where no matter what devices we're on, we can play the same or a similar game. We tend to think of the world as three screens, the television screen, the computer screen, and the mobile screen. Each of those are slightly different use cases of how we want to interact with experiences, but all of them should be social and all of them should be able to interact together over time.

So, we had this vision, and then the gaming industry had a similar vision, and the minute we talked, it became obvious that this was a win-win for everybody. The consoles would go social, the game developers could build social experiences, and that these would all be able to tie through Facebook. So, once you put two and two together, you've got five. And Xbox is very forward-leaning in building out their console beyond just a core gaming machine. And they got it right away, and they're moving very aggressively to roll this out.

Microsoft always had the advantage of understanding software and obviously it's the company's heritage. Understanding the power of Xbox Live and the network, I think, ahead of their competition. I just think Facebook Connect integration is another in a line of things they've done.

GD: And to your point earlier, what we've seen since that announcement, it was kind of an "a-ha" moment. It was an inflection point in the traditional games industry where it's like, "Okay, this is something that I think is really cool, and now it's becoming real." And the excitement since that announcement has been off the charts.

It's been a lot of fun taking those conversations to the next level, talking about how we use this technology rather than "Wouldn't it be cool if we had this technology?" So, I think we're going to start to see, this year, some early examples of that.

I think next year -- traditional games have long dev cycles. As the traditional games industry really wraps its head around the great capabilities here and iterate on it, we're going to see new forms of entertainment that we haven't seen before, that we're starting to see inklings of in different places. It really enables a new form of gaming that I think we're just beginning to see what this might be like.

You definitely implied at the Social Gaming Summit, more strongly I think, that you've seen things that are in the pipeline that are not able to be discussed now but which use it more effectively than what we've seen. Because I think the examples that we saw at E3, while cool, were a little bit superficial.

Don't get me wrong, I think it's cool that you can, in Tiger Woods, take screenshots and talk about what you've accomplished in the game, and publish that to your news feed, but I'm not jumping up and down about that. I think there are probably deeper places to go. You've seen examples that you think are...

GD: Very compelling. And I think in addition to seeing examples, the conversations that we're having are just mind-blowing. I'm really excited about the convergence between the two industries.

And as the traditional games industry gets more comfortable with social experiences and designs games around social experiences, and I think as the social gaming companies really move their games across multiple devices and think about how you have a game that spans the three screens -- the Xbox, the computer screen on Facebook, and the mobile device -- I think you can see both parties looking at this and going, "That's really cool." And the intersections are going to be really appealing.

One thing that was announced, also in terms of Xbox 360, is there's going to be a functionality with Facebook Connect to map your GamerTag friends list to your Facebook real world identity. And in some cases, there was some discussion about this at the summit -- whether some games are better suited to a real identity, and whether some are not. Because real world identity is a huge, huge part of Facebook, obviously. I guess it's just an interesting reconciliation of our cultural shift, almost.

GD: Yeah, there are several interesting elements to this. The first is that there's a cultural shift towards people being willing, excited, and preferring to use their real world identities online.

We all know that 10 years ago, you were as anonymous as possible online, right? And today, we spend a lot of our time putting our real world identities out there and sharing them, right? So, there's that cultural shift.

The second cultural shift is that because we have real world identities and we've been able to map this very large social graph where I have hundreds of friends now on Facebook, and I own all the consoles, and on each console I have just a few friends there... It's very clear to me that I have many more friends that have those consoles than I have friended on those consoles.

So, one of the compelling features of the Xbox integration is this idea of taking the Xbox social graph and using that to power my gaming social graph. And so we believe that this will help me discover on my gaming console all my friends that have the console as well, and so I can play with them more frequently and have new experiences with them, ones that I am not having today.

And we've seen this occur on Facebook.com, where as more and more people join Facebook and your social graph is more complete, you have the ability to have these social experiences with people you've never had before, and you're playing games with people who you didn't play games with before, with your family members, with your parents, with friends in remote locations. There's this new gaming activity happening that we believe will translate to the consoles as well.

So, that's a huge part of what we're doing with the gaming consoles. I think the next thing that's very interesting is this concept of identity in a gaming experience. There are many games where I think it's very compelling to use your real world identity. And we're seeing that on Facebook.com, where we have tens of millions of people playing games with their real world identities, right? It's a very positive thing. It's not an issue for them.

I think there's also a recognition that many game experiences are interesting because you're able to create a new identity and use your gamer identity in that game. And so, what's interesting here to me is that underneath every game identity, there's actually a real identity, right? You know, I have the GamerTag. But beneath all that, there's my real world name, my real world address, my credit card information.

Sure.

GD: It's just hidden, right?

Yeah.

GD: So that when you and I interact on Xbox, you just see my GamerTag. You don't see my name and address and so on. So, what we're doing with Xbox is allowing you to link the two, your gaming identity -- your GamerTag -- and your real world Facebook identity. And the chosen presentation method is where you see both.

I think for a set of users, that's fine where, you know, [attending Facebook rep] Malorie and I are playing, we know each other in the real world, and it's fine for us both to expose our gaming identities. But I think there are other cases where I only want to expose my gamer identity and not my real world identity.

And Facebook has always been about this ability to control the information that you share and our privacy. So, we're exploring those user cases very, very closely with not just the gaming companies but every gaming company and portal that wants to work with us, how to present these two identities and which identities...

At the platform level, you mean? Or at the publisher level or just at all levels?

GD: At all levels, yeah. This is something that many people are interested in. For some people, they care more about it more than others.

Right.

GD: And it's something we'll figure out exactly how to get right going forward.

There's going to have to be different approaches depending on who you're dealing with obviously and what their product is and all kinds of things. How closely do you work with companies when they come to you? Is there a learning curve that you have to deal with when dealing with some of them?

Because obviously, it seems like these startups that are really successful with games are just starting to pull in talent from the game industry, and there still isn't a complete meeting of the minds. Do you find that when you're dealing with companies, a lot of communication that needs to happen from your direction or both directions?

GD: Let's just talk about how to work with Facebook. We're an open platform. We provide documentation and policies. And everything you need to know to be able to build and run a successful app on Facebook is all on our website. So, that's part of the answer here. In terms of how do game companies figure out using Facebook as a new platform...

Or certainly Connect in terms of, there may be people that are developing games that will never actually develop Facebook apps. That's even a different way of looking at it. I mean, there's very savvy and smart and intelligent people at game companies obviously, making games every day, but it's a new headspace.

GD: We have an API that's very simple and straightforward that you can integrate into an experience very quickly and easily. We've had millions of people do this. I think it's very low complexity, and game developers are very smart.

It's more of the social issue, though. We've been talking, and I know things have been developing rapidly, but that seemed to be an emerging theme, maybe, from some of the coverage that came out. And the comments is that people do feel like there's maybe more of a desire to hook up than there's been an actuality to hook up.

GD: I don't buy that. I think if you look at a company like Playfish, they're formed by people that were formerly game developers in the mobile space, and they clearly get it completely. Companies like Zynga and Playdom, they have this mix of people that have built social games and have built traditional games. The two are mind-melding as we speak, and whenever anybody from different perspectives come together, there's going to be an interesting dialogue.

For me, I don't see conflict here. I really see convergence. And I think what you're seeing in terms of games on Facebook, you're seeing more of them, higher quality, better production value, more gameplay mechanics. The experiences are growing in richness at the same as they're growing in a use of social functionality. The games are better leveraging the social graph and better leveraging identities and better leveraging sharing stories that people respond to and connect with.

Obviously I think content should be left to developers, especially on a platform like Facebook where there's no physical shelf space or anything like that. But do you moderate anything in terms of content? I'm not too familiar with the app submission process. Obviously, the game consoles have an ESRB to serve those kinds of functions. Is that something that you've looked into or thought about?

GD: So, we're an open platform, which means that any developer can create an application on Facebook. We have around a million developers active today. And we have policies by which applications need to follow in order to remain on the platform. So, we police the platform. We make sure that apps are following our policies.

And then we have an app verification program. It's an optional program where they proactively submit their application to us, and we evaluate it in terms of following our policies, respecting our users, and how they interact in the user experience. If they pass verification, then we'll badge it and represent it as a verified app by Facebook. But all of these are optional programs.

Yeah, I noticed that verified app very recently, when I was using Facebook. Is there a good user response to that, the apps that have the extra level of endorsement?

GD: Exactly, yes. The apps that are verified, not only have they gone through a process where we ensure that they treat users respectfully which leads to a better app experience, which in itself generates more traffic, but the verification badge, we present in our app tree; we highlight apps that are verified so they get more placement on our sites. And that helps drive traffic also.

You know, you're speaking about treating users respectfully, I think that sort of leads naturally into questions of things like spam and user acquisition stuff. I know you've made efforts to crack down on things like apps that spam invites to your whole friends list. I don't believe that that's exactly possible, at least not at present. So, what are you feelings on those issues? I'm assuming that's something that's still pretty rapidly evolving.

GD: Well, I think our policies will continue to evolve to match the realities of the app marketplace. The goal for us is always to provide the user with the best possible experience and to help developers succeed. And so finding the right set of policies is very important to us, and they evolve over time.

We clearly want developers to treat their users with respect -- because one app developer's users, those users will come back to more apps from that developer but also use other developers' apps and use Facebook. So, really, I view this as a community that everybody should treat well and be good citizens towards, because we want those users to continue to use more and more apps going forward.

Yeah, it's something that [Playfish's] Sebastian [de Halleux] was saying. He said it at the conference, and then he said to me again later that he didn't think people picked up on it to the extent that he thought was relevant. Playfish doesn't spam or have really hardcore virality engine to its games. What it does is it just has a little link on the right side that says, "If you like this, recommend this to your friends", because they want people to recommend it to their friends when they want to.

GD: Yes. Playfish very much believes in what they call "quality requests". So [the game experience] is a quality experience. It's a fun experience that you're having, and you want to share that with your friends so that they can have the same quality experience and also play the experience with you. They're very pure about that, and I think they set the standards there very well.

Actually, Playfish, all of their apps are verified, and it's something that they see as very important to their applications, and to their users as well.

And what about Zynga? They're really high up on the rankings. Do you find the top developers work closely with you in terms of things like verification?

GD: Yes. many of Zynga's apps are verified as well. I think if you look at a sample of the top-end apps, many of them you see are verified. It's really a win-win. The apps get better, they get more placement, and the users like it as well. It's a good program.

Facebook games have a tendency to be simple, though they're getting pretty elaborate. But do you see the potential of things getting elaborate to the point of a full 3D Flash-based browser MMO with full progression?

GD: Absolutely.

Because that's well within the technological capabilities of Flash today.

GD: Absolutely. There's a great quote from the lead designer of EverQuest this week, right? Saying that they believe that the next great casual MMO -- it wasn't even casual I think -- will be on Facebook.

Because the challenge that some of the traditional MMOs have today is that they've built audiences but they're not bringing in any new users, right? And it's actually quite intimidating to join an existing MMO that's been around for several years where everybody's level 80, right? It's like the new experience is a little intimidating.

Whereas I think Facebook has done an excellent job of growing and welcoming people into the experience and very quickly people feeling like they're having a great time, they're interacting with their friends, they're playing games, and so on. And so when you look at the scale of Facebook, over 200 million active users, there's an audience there that's already starting -- I mean we have over 10 million monthly players of three games already, and we're a year into our platform. It's only going to grow from there.

We're at the scale of World of Warcraft on three games already. And the capabilities of Flash are growing tremendously as well. Flash 10 introduces 3D, and so we have 3D games today. So, you see all the pieces, all the building blocks, and people are starting to put them together. I think it's inevitable that someone will find that right combination that will just take off and become the next great MMO.

I mean, we're already looking at YoVille, which I would consider an MMO. It's over seven million monthly actives, half the size of World of Warcraft already, and growing much, much faster.

That brings us nicely to payment and the ability to monetize users. A lot of the discussion at SGS was about monetizing; it seemed a little crass when you come from the game development side, where people think artistically. At the same time it's obviously super-duper relevant to be concerned with it because Facebook developers are not getting $60upfront. They're getting incremental payment as payment comes from users, and they have to fight from it in a totally different way.

GD: Yeah. I think that's what you were seeing, that we have new revenue models that the traditional games industry is really not familiar with. But what you're also seeing is that in traditional games revenue, large publishers lost money last year, right? And I think all of them see as a shift from retail distribution to online distribution, and they're figuring out how to manage this transition. It's a big deal, what everybody expects with this.

Now, the social game companies started with digital distribution, online distribution. The models that are thriving on Facebook include advertising and in-game transactions. Neither of these are prevalent business models today in the traditional gaming space. It's very much a "Pay $60 at retail," or "Pay $15 World of Warcraft," right now.

So, there are new revenue models. And I think whenever there are new revenue models, there's a lot of interest in how they work and how to optimize them from monetization. And so, I think from a social gaming perspective, what you're seeing is an evolution in the thinking and the iterations in how they think about these topics.

And I think when the traditional game folks show up, they're like, "Well, why are you so focused on these things? Because you know, we've kind of cracked monetization even though, you know, we lost money last year." Yeah, you made four billion dollars. They know how to make four billion dollars. "So, why are you so focused on how you make money?" EA's very focused right now on making great games, not necessarily on how to develop new monetization models.

At the conference, there were a lot of people proposing payment solutions of offering payment solutions. There were a lot of potential routes for payment solutions, whether it's anything from PayPal to, you know, in Europe, often mobile, or pre-paid cards like Nexon uses for MapleStory and a number of other people use, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.

First of all, it is worrisome to you that the payment solutions are various and disparate, or is it strengthening from your perspective, that there's not a simple obvious solution, that there's a lot of choice?

GD: We're an open platform, so the parties are able to implement whatever makes sense for the users. I think what you're seeing is a range of options that we think is good. One of the reasons why the space is monetizing so well is because these monetization systems exist, right?

That's really one of the big takeaways from the conference, how well social game companies are monetizing. They're doing very, very well here, thriving in a very new space. To be two years into an industry and to be doing this well is remarkable, particularly in this economic climate. So, we think that's a good thing.

There was also some discussion, and this is particularly why I didn't see there being any consensus. I was a little surprised, I can't remember exactly the context, but someone said, "Raise your hand if you're interested in this." And it was kind of, "Oh, not really." It was a payment solution offered directly via Facebook or from Facebook at a corporate/platform level. Do you have interest in that? Do you see a need?

GD: So, we get a lot of requests to provide a platform-based monetization model. We want to help developers succeed as best as we can and also help users have a great experience. We have a gift shop on Facebook.com that enables our users to buy gifts using a virtual currency called Facebook Credits. And that's done very, very well for us. We're thrilled with that business, and it's growing.

Birthday cakes and that kind of stuff. I see those all the time.

GD: People love to buy gifts and give them to their friends. It's a very fun, engaging activity. And so, having seen the success there and hearing the requests from developers that this would be of interest to them, we have begun testing the user Facebook Credits by offering them to developers so that users can use Facebook Credits in an application to buy things. We're very early on in the test there, and so far, the results look good. We have a handful of apps live today.

Malorie Lucich: Yeah, (fluff)Friends, PackRat.

Malorie Lucich: Yeah, (fluff)Friends, PackRat.

GD: So, you can go up there and take a look at it. Essentially, the way it works is that when you're at the point of transaction, you're presented with the "Pay With Facebook" that you click, and then we handle the transaction.

We believe that this has a lot of potential to be beneficial for a user because the user experience can be much smoother. They're not redirected out of the party. They stay in the flow. Secondly, there's a Facebook-branded button, and since they already have a high level of trust with Facebook, they store a lot of information with us, they're more likely to go through the transaction. We believe there's a potential lift for users that they love this stuff.

For a developer, same thing. It's like, "happier user, more transactions." It's potentially very, very appealing to them. That's what we think. We're testing this out right now, and as soon as we have more information to share, we'll share that.

Have you made any decisions or made any public information on what the split in terms of Facebook and...

GD: We have not.

I'm not shocked. [laughs] But I have to ask.

GD: Sure.

Facebook in just a few years sort of came from nothing and became massive and a lot of the companies that have found a lot of success, particularly Playfish or Zynga or even ones that came from people who are established, they still are companies built up from very little and very quickly became larger.

So, typically, talking to the game industry, you're talking about working with really established companies who've been around for a long, long time.

Very often, when companies are trying to attract people to them, they'll do tie-in marketing or something like that, they'll work with established companies, well-known brands. A lot of what's successful about Facebook and the companies it works with is this startup mentality, however.

GD: We're completely open and neutral to that. We encourage everybody to use our tools to build great experiences. We have seen great experiences come from small developers and great experiences come from large developers. And they approach it differently, and we don't really distinguish between them.

I think, we've reached this point... It feels sudden. We saw it coming.

GD: The crystal ball.

A little bit. When I say we saw it coming, we didn't see it coming from five years away. It seems like there's so many places to go right now. You know, whether it's making iPhone or other smartphone applications; Xbox Live Arcade became an opportunity, and now Xbox Live Indie Games; PSN, WiiWare; Facebook, and of course MySpace and other competing social networks. There are so many places for developers to go these days that it's almost astounding.

GD: It's true. In the game industry, we've had two or three platforms for many years, and the dream was always that there would be one, right? [laughs] And so you would never have to write the game to multiple platforms.

And the industry has kind of gone the other way where now there's a plethora. They're everywhere, all different types, shapes, and sizes. People are experiencing the world through different forms now. The miniaturization of the chips is remarkable. I have three smartphones and three game consoles. It's insane.[laughs] And when I'm interacting with those devices, game playing is a key activity I want to do.

And so what you're seeing game developers do is push out the game experience to every device, to everywhere. I think there's a shift away from everybody going to one place to play a game, to the game being wherever you want to play it. And I actually think this is a great thing because it's hard to get everybody to go to the same place at the same time. It just is. People have tried forever to do this, and no one has succeeded yet. And so, I think this concept of pushing the experience out is the right way to go.

It's interesting because it seems like each platforms is staking a claim on what it offers. At least in my use patterns and what I'm observing. It seems like it might get even more silo-ed. PS3, 360 for big, immersive, large-scale, and high-budget games. Wii for innovative, motion, casual. Facebook, social. iPhone, quick hit. Of course, obviously, people blur the lines a lot, and sometimes it pays off, sometimes it doesn't. It's interesting to see the evolution.

GD: Right. We have a unique view here, which is we believe that every experience will be social, and that having a social experience is more compelling than a solo experience. So, you know, today, we have Facebook Connect on iPhone and coming soon to Xbox. We believe that in some point in the future, every device will be Facebook enabled and will be social and that that will make the experiences will be more compelling no matter which device you're on, no matter which of those screens I was talking about you happen to be in.

Sure, you might want to have a different social experience depending on whether I'm with a group of people at a party, in front of a TV screen on a Friday night, versus me solo on a train commuting to work and playing a game. But all of them will be social, just different flavors of that.

I'm a pretty big believer in the fact that there's always going to be a room for solo narrative or solo linear progressive experiences in media. I don't think movies are going away, I don't think books are going away, and I don't think single-player games are going to go away. Obviously, they less obviously hook into Facebook.

GD: Let's take each of those experiences, and what you'll find is they're inherently social. You watch a movie in a theatre with a group of people, right? It's rare that you go to watch a movie by yourself. We're also seeing that it's very common for us here for instance to be watching television and have a laptop open and using Facebook. I just watched the USA-Brazil game, and I had one eye on the screen watching the soccer, and one eye on Facebook. We were sharing our experiences over Facebook, and it made the game far more fun even though I sat solo watching it.

There's an interesting aspect to that. Not only was I watching the game and sharing it with my friends online, but I had Facebook friends that weren't watching the game who started watching the game because I was watching it or because other friends were watching it. And then my conversation the following Monday morning at work wasn't just with the people that saw the game but with people that didn't see the game. There suddenly is a solo experience of watching a soccer game that's turned into a very social experience.

Books, you know, Book clubs, hugely popular right now. My theory is that we're inherently social creatures, and technology has kind of pushed us into more and more solo experiences. And now technology has gotten to a point where it can connect us all again. And given the choice of a solo experience and a connected experience, people are opting for that social connected experience.

For the inauguration on CNN, we had the ability to watch the inauguration and then read your friends updates. We had millions of people updating their status. Here at the office, we had a lot of people in D.C. I was again watching it at home, and then I had friends out there in different locations, and we got to share that experience together using Facebook.

This is a new way of experiencing things, but it's really kind of a throwback to how we all used to experience things. So, this is why we think that everything will be social from a technology perspective because it used to be, and we're just kind of finding our way back to that.

We are sitting in Facebook's offices in Palo Alto and Silicon Valley, and you're friends are probably highly connected people. I mean, I watched the election results in November at a Google employee's house with a Twitter feed on the screen at the same time. But not everybody has that set of friends. Are people using Facebook being this engaged with that connected experience across the board, or is it filtering in?

GD: It is. It's across the broad. We have over 200 million users. This is a huge audience here and growing rapidly. About 70 percent of our userbase is international at this point. It's global. It's not just Silicon Valley.

I know it's not just Silicon Valley. But is everyone as connected? Does your general audience use it, or do you have core, heavy users? How do you perceive that?

GD: That's a tricky question because there are lots of pieces to that. What we see is people are very engaged across the board. There's a virtuous cycle in that as people share more, other people share back. You'll tend to it yourself. It's like there are social patterns that occur, so if you start posting links to interesting articles, you find your friends doing the same thing. Suddenly, my social graph becomes a way to discover interesting articles, and they go to the newsstand less.

And so we see that in every kind of category. Like photo sharing. We're now the number one by far photo-sharing site in the world. Game playing, if we're not there already, we're getting there. So, everything that people start to do socially just amplifies and grows like wildfire.

You envision a world where every piece of media consumption or experience can be socialized via Facebook in some way. Do you think the volume of updates at some point will actually outpace our attention for them? That it could become spammy?

GD: Well, one of the great things of the social graph is it's a filter on all of our experiences. What you're seeing is that as you're looking at your Facebook messages, there's no spam in there. It's all from people you know, and they're meaningful messages. Whereas I look at my email list, and most of it spam now. So, the social graph is an incredible filter on the world. I think that it naturally reduces spam. It increases the kind of signal to noise out there in the world. I think that's one part to this.

The second part is that it seems like our appetite for information just continues to grow. Our feed is real time, and there's more and more consumption and creation since it became real time. You know, the amount of information in the world is just going to continue to grow, and I think we'll get some pointers on how we filter that information. And I think providing a real time place, forum, and then having my social graph filter it is the right model going forward. I haven't seen a better model yet.

I guess the last thing I want to touch on is the stability of the platform. As we all know, as users of Facebook, Facebook itself tends to evolve rapidly. When developers are working with it, what guarantee do they have that their apps are safe from being evolved out of the system? Have you reached a point where things are stable and developers can approach it knowing what they're getting into?

GD: I think one of the great things about Facebook is we're constantly evolving it. It continually gets better and better and better, and our audience continues to grow and grow and grow. We think very carefully and very deliberately about the changes we're making. They're all designed to increase our userbase and increase engagement. And that benefits everybody.

You know, you look at the traditional game consoles that are pretty static. This generation is great because now you can get a system update. Remember before that? You couldn't. And the ability to make changes to the platform and evolve the platform is very, very powerful because we can get feedback form our users, from our developers, and incorporate that into the evolution of the platform. We continually look at what's working and what's not, and chart a course for success.

The platform itself is very stable. People have built successful applications and successful business on it. But it will continue to evolve, and there's still a long way to yet. We're just at the beginning of mapping out a social graph and building a technology and service that everybody in the world is happy to use.

Obviously, Facebook is primarily successful in certain territories. Other social networks have bigger success in other territories. Is that a gap that you see bridging, or is that something you see solidifying?

GD: So, globally, by far, we're the largest social network and growing the fastest.

Specifically, let's say, China, you know, is a place where Tencent has a huge presence or whatever. Do you see that as a place you can go?

GD: Why, absolutely. One of the things we're seeing globally is that because Facebook is global, that makes it a much more compelling social network in a particular country because people want to connect with everybody they know. There are certain territories where there are local networks.

Yeah, I'm on Mixi in Japan. I have some Japanese friends that have come onto Facebook, but they tend to be really internationalized people. Actually, I don't touch Mixi anymore. At some point, I felt like I had to start a Mixi account to stay in touch with people in Japan, but I guess it might be changing.

GD: So, what we see in some countries already is that Facebook rapidly overtakes them because of this global aspect. The second is what we see is that people sign up for the local network and Facebook, and over time, we can overtake the local network.

I mean, we've never believed that we will be the only social graph out there. We believe there are different mappings of the social graph. Our goal is to be the best mapping and to really focus on the social graph as a way to help people connect and share. And that's out number one focus and will continue to be for a long time. That's a universal desire. And over time, we'll continue our growth and become the best social graph out there.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like