Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Empathy is the most important game design skill you could ever develop.

Creavity, logic, problem-solving skills, sense of humor, knowledge of probability, statistics, systems theory, information hierarchy, storytelling… the list of desirable game designer traits seems like something out of Da Vinci’s CV. “But what is the single, most important thing for a game designer, Mark?”, you ask, fully expecting me to contort my face for minutes before squeezing out a non-answer.

I surprise you like a ninja coming out of a cookie jar, as I throw my answer at you as quickly as my chocolate chip shuriken: the most important trait for a game designer is empathy.

If you don’t know how people work, you can’t make stuff for people to interact with. The most talented and technical designer that lacks empathy will make something that only he/she can enjoy - or, at the very best, something that can only be enjoyed when the designer is around to explain how to “play it the right way”.

My first few years of game design study and practice were very much focused on the “object” of games - how these systems actually work and how you go about designing them. As I got more experienced, I noticed that even as my understanding of the “cold” aspects of games got richer and deeper, I was still unable to design things that didn’t suck. Sure, I was now able to understand and communicate clearly why it is that my games suck. And other people’s games too, of course. There’s nothing more comforting in defeat than realizing that someone else sucks even more than you do.

Even though this critical detail and technical knowledge is super important, I was still missing something. And crossing over this chasm that exists between “good” and “excellent” has been my personal journey for the last couple of years, a quest in search of that something, the truth, the Holy Grail of design: “Just What The F*** Is Wrong With People?”.

Finding out what those drooling morons at the gamepad/keyboard/dancing mat are actually thinking when they don’t get your brilliant design is the endgame. You can never be too good at it, so expect to sharpen this skill for the rest of your life.

This article is the first of a series where I will explore different aspects of how the disconnect between your worldview and your audience’s can spell disaster to your project like a dog playing Jenga. So before I wrap up for this week, let’s discuss the concept of “empathy” in game design a little further.

Game Design Is Not Magic

So here goes an earth-shattering definition of satisfaction, do tighten your seatbelts:

Satisfaction is the fulfillment of expectation

Not very academic-sounding, I know. Not very wordy, either, and frankly just sounds obvious when you say it out loud. But this is a powerful definition to work with, because it forces us to focus on this core idea: everything we do in our game can be viewed as either expectation-setting or expectation-fulfillment.

This is a particularly useful set of lenses with which to look at your design, as it is simple to understand, use, and communicate to your teammates. It also permeates all the aspects of your game: design, sound, visuals, story, the wording on your trailer, the text on your menus, your press releases, the description on the storefront. It helps you think of your whole product as a game design problem.

This is also a tool that requires you to keep your attention on the player at all times. “Is this good enough?” ceases to be an unanswerable question and turns into action. It transforms into a new question. “Is this what our audience expect it to be?” demands you to go see if it is true. It can be tested, it can be measured, it can be answered.

Game Design Is Magic

But wait, satisfaction is not what we’re looking for, right? At least that’s how I see it. I don’t think we’re in the business of giving people what they want. We’re f***ing artists. What we really want is to cross that chasm. To build something truly awe-inspiring. We must take our understanding of what people want, and then surprise them.

Here’s another reductionist, blanket-statement definition that won’t make you popular at the nearest symposium:

Entertainment is satisfaction and surprise

If you work with that, you get something like a hierarchy of needs for your design: make sure you understand your audience’s expectations, make sure to not disappoint them, but then offer something surprising. Something they wanted, but they did not know it until that point.

So I like to compare game design with magic: the technique required to execute a prestidigitation trick is worthless by itself. Sure, you can’t do magic if you can’t even tie your shoelaces properly, but real greatness comes from understanding people better than they do themselves.

People want to believe that you’re taking them for a journey by the hand, they want to go to Disneyland, they want to have the feeling that you know what is good and that they can trust you to deliver that. It is a macroscopic version of a purple loot drop: “I know there’s something I’ll like in there, I just don’t know what it is yet”.

This kind of trust is hard to earn. You must be two or three steps ahead of your player, and unfortunately we’re usually one step behind most of the time. Our job is harder because we do not control anything directly: point of view, pacing, information, pretty much all elements that must be manipulated for good entertainment to sprout is out of our hands when the game is being played.

So those magic guys have it real easy, right? But still they focus more on understanding their audience than we do.

This article series is my attempt to contribute with my limited experience on the subject. This first one was very theoretical and fluffy, but I already have the themes for the next three, and they are all rock-solid: encounter design, reward systems and tutorials. So please do stick around if that’s something that interests you, and I’ll see you next week.

***

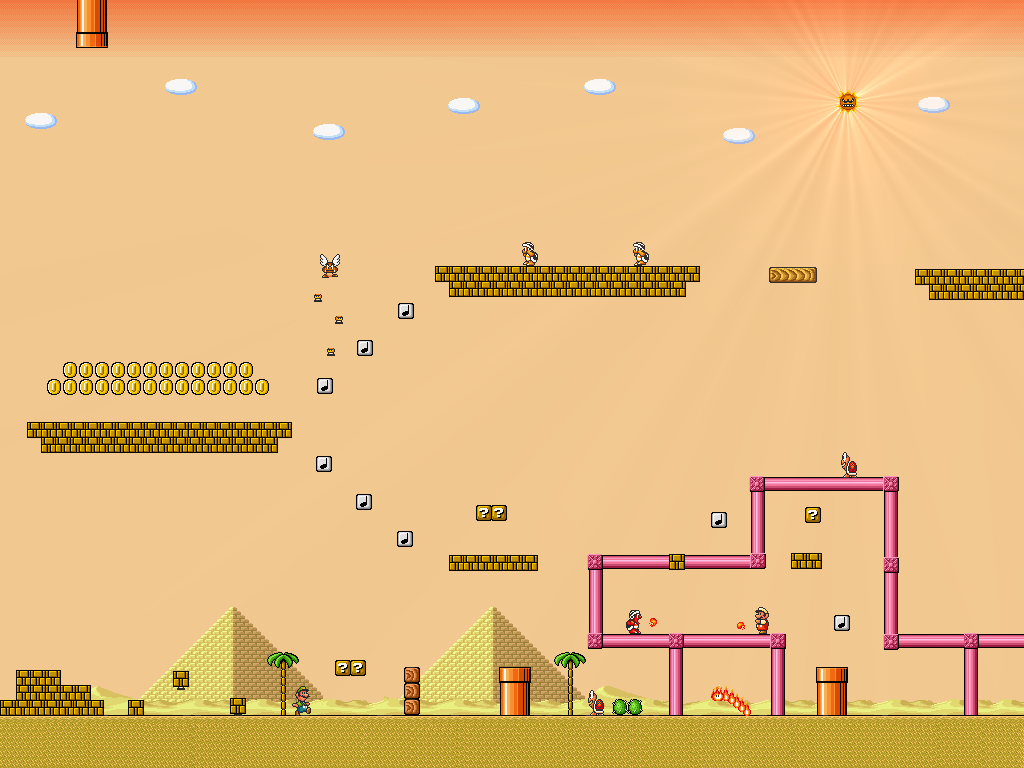

I still remember playing Super Mario Bros. 3 and trying to fly over the stage, my 12-year-old mind filled with the fluids of pride and a tiny bit of mischief as I expected to “break” the game. Almost 20 years later I still remember how magical it was to find all that stuff waiting for me in the clouds, as if old Mr. Miyamoto was talking back to me, talking in a language that only games can speak, saying “Hello, Mark, I was waiting here for you” and smiling like the smartass that he is.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like