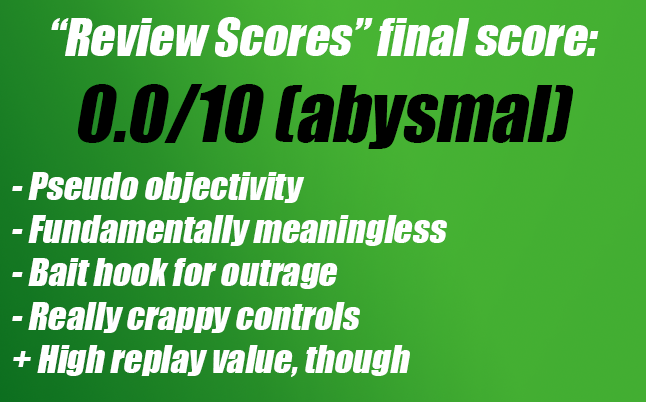

You don't need to read Katherine Cross' opinion on game review scores. Simply scroll to the bottom of the page for her numerical rating of game review scores.

I began a long-ago column with the words “numbers are a compulsion” as a succinct way of illustrating how the products of RNGs can, when tweaked correctly, profoundly motivate play. But as I look back on that phrase, I feel it might’ve been better used to describe the numbers that truly bind us all together in this industry: review scores.

For a variety of reasons, it’s long past time we stopped using them.

***

Controversies over scoring are nothing new, but the past month has seen an absolute bumper crop of outrage and harassment directed at game critics who gave reviews that some particularly entitled gamers deemed incorrectly scored. Lucy O’Brien’s IGN review of Naughty Dog’s Uncharted 4, Daniel Starkey’s GameSpot review of Stardock’s Ashes of the Singularity, and Rowan Kaiser’s review of Paradox’s Stellaris all attracted outrage from fans of the games who felt that the games were scored unfairly.

Accusations of irrational bias accrued to all three: O’Brien was unaccountably accused of giving Uncharted a preliminary score of 8.8/10 because she “hates men” (the final review including multiplayer scored it at 9.0); Starkey was accused of giving Stardock-published Ashes a 4/10 because he disapproved of the GamerGate movement, which Stardock CEO Brad Wardell publicly supported; Kaiser was attacked for his 6.5 score because he wasn’t a fan of a pro-GamerGate critic that had been mentioned positively in a conversation among Paradox staff.

On their faces, these accusations are staggeringly idiotic and border on self-parodying paranoia. Upon actually reading the reviews, such a judgement becomes inescapable. All three were professionally written, focused entirely on the context of the games themselves, never once mentioning any of the outside personalities or issues that the conspiracy theorists claim to have jaundiced the reviews. O’Brien’s review marked down Uncharted because of what she deemed to be a weak third act wherein both story and gameplay became repetitive and dull; Starkey’s review situated his opinion a comparative history of strategy games, their tropes, and mechanics; and Kaiser explained at great length why he felt Stellaris’ mid-game (a critical phase for any 4X title) was severely wanting.

But all of this is almost beside the point. The outrage, to look at the tweets, harassing comments and emails received by all three writers, fixated with an obsessive rage upon the scores given by each reviewer and not the qualitative content of their arguments. The actual source of the outrage lies, of course, in things like consumer entitlement and--in O’Brien’s case--a depressingly obvious misogyny. Yet the numerical scores are a thick focusing lens for all that rage, concentrating and refining it into a simple, memetically powerful opinion that can easily drown out nuanced discussion.

Here’s why.

***

Numerical scores give a false impression of objectivity. We are taught to see numbers as inerrant and objective; all measurement is expressed numerically. A centimeter is a centimeter, no matter who you are, what your personality or opinion is. This is how many gamers are taught to approach review scores.

If a scientist takes the temperature and sees a reading of 20 degrees centigrade, but pronounces it to be 50, even the most untrained observer would pronounce him or her to be objectively wrong and quite possibly bad at their job, provided the thermometer was proven to be working correctly. To many gamers, review scores represent just this kind of temperature reading: an objective, numerical measure of a game’s quality. Anyone whose score deviates from an emergent norm is clearly doing their job poorly--that was the main argument levelled against Arthur Gies for his Polygon Bayonetta 2 review, which gave that title a 7.5, and Carolyn Petit for her GameSpot video review that gave Grand Theft Auto V a 9 out of 10. They were farther from the bell curve’s mean than was acceptable and this proved they were bad, biased critics; they got one temperature reading and then pronounced a wildly different one because of their failure to be objective.

Numbers seduce us into thinking this way. In so many other areas, they are indeed reflective of objective facts--disprovable only by recourse to methodological critique. But in the world of video games (and film, for that matter) they perform the neat trick of distilling the essence of what is an entirely subjective opinion into a pseudo-objective package. This effaces every nuance of the critic’s viewpoint.

"Numerical scores give a false impression of objectivity."

What may be an 8.5 to me is very different from what merits an 8.5 to another critic. And what’s worth marking down three tenths of a point? Is my site’s 6.75 different from another’s? What is the difference between a 9.0 soundtrack and a 9.5? What does a 10/10 control scheme feel like? Critics give scores on the basis of rubrics provided by their publications, often as not, but even there the score is still the product of a gut reaction; it is a melange of values, emphasis, and personal judgement. It can never be objective.

Still, its brevity and its intimation of scientific truth make it very easy for particularly angry gamers to fixate on. The substance of a review--that is to say, the actual words used by the reviewer--may figure into their rage, but the score is the thing. It is impossible to make a clear bell curve of paragraphs and column-length opinions in all their “on the one hand this, on the other hand that” wobbliness; it’s very easy to do so with numbers. O’Brien’s critics would have had a much harder time distilling their outrage if they couldn’t point to other scores, both among games she’d reviewed, and how other critics reviewed Uncharted 4. The outrage might still be there, but it’s harder to make “she said that the third act was mechanically and narratively lacking!” a rallying cry that’ll focus a harassing dogpile.

Similarly, Petit would have been attacked either way by gamers who felt that mentioning the obvious misogyny baked into GTA’s universe was beyond the pale for a review. But the lack of a score would’ve made it harder for them to hang their rage on something quantifiable, on the point that feminism supposedly stole from them.

***

It would be easy for me to sit here and say that this is entirely the fault of a vocal, immature minority among gamers for whom reading comprehension constitutes an insurmountable challenge. But it isn’t. These gamers react to scores in this way because our industry encourages consumers to view scores as nigh-on-objective assessments of products and all but sells them in that manner. Why? Because that’s often how corporations themselves use them.

The game industry is addicted to review scores. Frighteningly, review scores have even determined how much developers get paid. These numbers are used in marketing, box art, and flaunted at conferences and conventions; no wonder they figure so prominently in the conversations of ordinary gamers.

As ever, when we fixate too deeply on the asinine views of angry commenters, we ignore the larger structures that create them.

But I fear that this is also why review scores are here to stay. They are a business, and they are a way for many publications to feel as if they have influence over the direction of video game companies, with their little weight dropped onto Metacritic’s vast scales. Yet just as they are a focusing lens for outraged fans, they perform the same function for companies. A score was at the heart of the Jeff Gerstmann scandal at GameSpot, who fired the reviewer because of pressure from Eidos Interactive over a 6/10 “fair” score given to Kane & Lynch: Dead Men and a 7.5 given to Ratchet and Clank by a writer he oversaw there.

"Any reviewer having the courage to use the entire scale deserves praise in an age where too many of their fellows feel that below a 7 thar be dragons."

When a reviewer has the audacity to dip into the lower half of a 10 point scale the scene is especially set for outrage. If a 7 is mediocre, and 6.5 is outright bad, and a 4 nigh on unplayable or broken, what on earth is a 1, 2, or 3? “Opens a black hole that ends all life as we know it”? “This game killed my parents and now I want revenge”? “The game has bad controls and also smallpox”? This is why this sort of thing gets beyond ridiculous. Any reviewer having the courage to use the entire scale deserves praise in an age where too many of their fellows feel that below a 7 thar be dragons.

But again, all this stupidity could be avoided if we were forced to focus on the substance of the reviews rather than the score at the bottom. In the meantime, game companies should follow the sterling example of Paradox and stand up for diversity of opinion in the games press athwart the conspiracies peddled by some fans.

The actual words used in reviews will still have the power to unsettle corporations and the gamers who let themselves be led by them, of course. Controversies and frothing-at-the-mouth debates will continue. But the absence of numbers that can be deemed objectively “too low” will only be to everyone’s benefit.

Then we can talk about what was actually said as opposed to a decimal pointed number that means next to nothing.

But for those who depend on them, let me conclude my essay thusly:

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like