Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

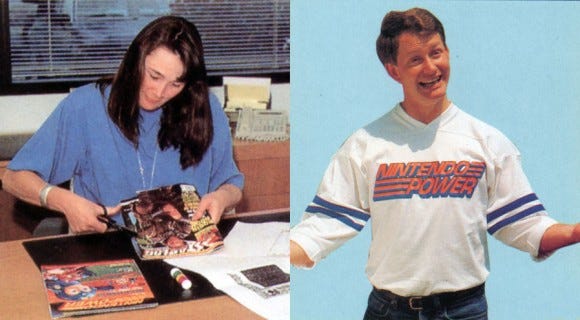

Nintendo Power founding editors Gail Tilden and Howard Phillips share their memories of launching -- for better or worse -- one of the most influential periodicals for those of a certain generation.

Sometime in 1987, Nintendo of America's then-president Minoru Arakawa -- the son-in-law of Nintendo Company president Hiroshi Yamauchi -- made the bold decision that players of his Nintendo Entertainment System console needed their own magazine to read.

There had been video game magazines before -- several, in fact -- but they'd all died along with the entire video game industry during the infamous crash of 1983. But if Nintendo was able to prove that kids were still interested in buying new games after all, he thought, perhaps they could prove that they'd be willing to pay to read about them too.

Thus, Nintendo Power -- sort of a combination of the free Fun Club Newsletter Nintendo was already sending its fans and a print version of its game tips hotline -- was born. It was the first of the new wave of video game magazines, and it managed to outlast all those who followed -- Electronic Gaming Monthly, GamePro, Game Player's, VideoGames & Computer Entertainment, and the list goes on -- until the final issue was released on December 11, 2012.

Nintendo Power founding editors Gail Tilden and Howard Phillips were gracious enough to share their memories of launching -- for better or worse -- one of the most influential periodicals for those of a certain generation.

Gail and Howard were an unlikely combination -- she was the company's head of marketing and PR, and he was the Gamemaster, Nintendo's in-house video game nerd -- but together they managed to produce a magazine that somehow toed the line between being a marketing tool for selling products and an everything-you-need guide for telling game players what they should play and how they should play them.

Howard Phillips: When we first launched the NES in 1985, we figured out very quickly that kids were just dying to get extra information about the games -- not just new games that were coming out, but also how to play them. We knew that in part because the Famicom had preceded the NES in Japan and we were seeing that phenomenon in Japan as well. So we decided that we would set up a mechanism that would help kids out with the games, and that's when we started the game counseling line.

I had about five or six guys who worked for me who answered questions on the phone, like how to find the third coin in level three, that sort of thing. But that was only one (expensive) way to solve that problem. We looked at other ways, and one way was to use the registration cards to send out information to the kids in the form of the Fun Club News.

Click for larger version.

Gail Tilden: I was an advertising manager, so I was doing PR and advertising for the NES. We'd been doing a lot of inserts in both the hardware and software, trying to get people to send us their names and addresses. In exchange, they would become a member of the Fun Club and receive the Fun Club News. That's what was going on in 1987.

The database was growing bigger and bigger, and I think we were at around 600,000 people when we made the decision that we didn't want to continue having a free magazine. It was creating a big burden to send this out.

HP: We were paying for it. It was good that we did that, because it eventually grew to over 100 people in game counseling who were answering questions. We really needed to respond to that in a forceful way.

GT: Ultimately, it became a burden because the database was growing so quickly, and we decided to start charging for it. That didn't mean it was extremely profitable to do that. In fact, it was still a marketing expense. But it helped pay for the cost of sending out the information, certainly.

Also right at that time, we came out with the very first Nintendo Player's Guide. That was one of the first times we had something where we had a lot of information and maps, and the kind of support they were giving games and gameplay in Japan. In fact, we used a Japanese resource to create that publication.

Nintendo Power was a combination of that idea and what was happening with the Fun Club News. Mr. Arakawa saw that there were several magazines in Japan that were supporting gameplay in a way where they used maps and helped people finish the games, and therefore helped consumers be more satisfied with the games. He wanted to follow that kind of format.

Click for larger version.

HP: Looking at Japan with Famitsu and Famicom Tsushin and things like that…I would get these really thick, dense magazines as part of the regular weekly shipments from Japan. I'd get these in the warehouse and I'd crack them open and look at the cool new games that were coming out. I'd almost get down with a magnifying glass to look at screenshots and things like that. It was natural for us to think that the kids in the U.S. would be eager to have that as well

GT: Mr. Arakawa was trying to capture the kind of print medium culture in Japan where kids would buy magazines like Jump and read them cover-to-cover every week. They had huge subscription bases. His own kids, who were born in the U.S. and knew how to read Japanese, would do the same thing. He would buy them copies of everything and they would just pore through them. He didn't feel there was a cultural bias. He just thought that no one had really hit on it. He wanted to use people who were involved in the Japanese print magazine business to help us make a magazine that would approach it editorially from that same point of view.

HP: So that was when Gail and I started up Nintendo Power. Gail was really the driving force behind the whole thing. I was more of a player's advocate for things that had to do with games specifically, like which ones were cool and why they were cool. When we were doing press checks, I would always say things like, "This screen is mirrored," or "This guy isn't in this area of the game." I made sure it was accurate so that it wouldn't cause more grief to send it out to all of the kids.

HP: It never would've happened without Gail. Gail is one of those incredible work powerhouses -- super smart, super energy, very creative, selfless, and on and on. She was the driving force behind getting it done.

Mr. Arakawa would come up and say, "What do you think about this?" And he'd get an honest answer from her and a believable story about what was possible and what wasn't.

GT: The company was growing and maturing, and we were getting a much bigger marketing and advertising department, so I wasn't running all of marketing communications at that time. I had when we were tiny.

I needed to come in, like, tomorrow [out of maternity leave, to start on the magazine], and I had a baby. The gals at work used to laugh when I would bring my son in, who was like six weeks old, and I'd hand him off to someone in the office and I'd go into some big Japanese meeting to discuss Nintendo Power.

They didn't know what to do because he was crying. They fed him water, and I went into a crazy fit over it. I think I was so dumb that I didn't know it would be fine, and they were so dumb that they didn't know...none of us knew what to do with a six-week-old baby in the office while I was attending these meetings.

But it worked out. He's still thriving.

HP: Gail was very strong at being a publisher and an editor. Nothing got by her, just from a pure print production standpoint. Also, she was pretty creative for print production. But when it came to the games, I knew that if I didn't catch it, it would get printed, and we'd print a million of them and send them out to kids.

GT: The biggest thing was the masthead, of course. Nintendo's marketing slogan at the time was "Now you're playing with power." The idea was to stay within what we were doing in marketing. We talked about naming the magazine something like "Power Player." The trademark for that wasn't available, not because someone had a video game magazine named that -- it just wasn't available.

That was the deal with Mr. Arakawa. In this particular realm, he had very strong ideas. He came back and said, "The 'now you're playing with power' part? That's fine, whatever. But whatever name you come up with for the masthead, it has to have the word Nintendo."

We had a small agency called Griffith's Advertising who did our covers, so the first issue had a clay model done by Will Vinton Studios in Oregon, who at the time did a lot of famous claymation, like the California Raisins. They molded that Mario for us to take pictures of.

HP: That issue she pulled together with Tokuma Enterprises in Japan, which is kind of like the Time Corp of Japan. I believe they were doing Famicom [magazine]. They were supportive of us, and served as executive publisher or something. We did all of the printing over there, and we were initially doing all the publishing over there with Work House, which is this small design company in Tokyo.

GT: We enlisted some teams in Japan to help us. The magazine was co-published, really, by Nintendo of America. They used a studio that had expertise in making these kinds of layouts and video game maps and that kind of thing to support us. We directed how many pages, what we wanted to talk about in the magazine, set up regular columns like Classified Information and Video Shorts and that kind of thing, and they provided us with the graphic support. We wrote the copy.

HP: When you look back on it...in modern times you'd think, "Well, they probably had a staff of 50 running around doing all sorts of different things." No, we did not. It was only about a half-dozen people scattered across Nintendo of America and Work House and Tokuma in Japan that really got things going.

After a while Gail started getting writers on staff, but it was really thin to begin with. It wasn't thin because Nintendo was one of those companies like Microsoft who would get twice the work done with half the people. It was just because it was all new, and everybody was doing so many different things at the same time.

We just did it. Doing things didn't mean going out and hiring people. Doing things meant doing them, and then after figuring out what could be done, maybe hiring people who could replace you so you could move on to the next project.

I don't know if you've ever worked at a small company when you're doing a startup thing, but everybody does everything. Arakawa would come out and help pack brochures for the trade shows and stuff like that. So would his wife, Yoko. Everybody worked together. But I had a lot of jobs. When we started that, I was still a warehouse manager responsible for shipping all that stuff in and out.

GT: Howard and I went to Japan to work on the editorials and layouts. Pretty much every issue involved two trips to Japan. Usually, Howard and I made one, and the production manager made the second. We got over there to work on the layouts and figure out what we liked and didn't like.

We were in some hotel suite, with everyone smoking on the tenth story of some hotel in Tokyo.

[In Japan] there's a very different sensibility about certain kinds of color, especially with greens. They tend more toward the olive greens, or oranges. They have a very different sensibility about fonts, and what the font reflects, and background colors, and that kind of thing. I was directing them that I didn't like it or wanted to change it, and there was all this uproar.

So Howard was trying to be funny and got everyone to be on the same team. It wasn't that he was saying "don't listen to [her]," but...he was saying something about me being the Dragon Lady. "Don't worry about it, she's just the Dragon Lady."

Unfortunately, that is something that really stuck, and from 1987 until I left Nintendo, the creative people that I worked with over there all knew that I was the Dragon Lady. That didn't do a lot for my reputation and the idea they were working with an American woman who was supposed to be the boss.

While we were going through all these traumas of trying to get on the same page, the art director quit. He didn't want to work with me. [laughs] He walked out. He didn't really want to get on board with my direction and stormed out. But there was a gentlemen there who at the time was a more junior person in our staff who stepped up and said, "I know what she's asking for, and I know what they want." I don't know if he believed it, but he made it appear that it wasn't so unreasonable that we were trying to do something more appropriate for our market.

That gentleman, Mr. Orimo, became the art director for the magazine, especially in terms of the Japanese construction of maps and gameplay. He ultimately moved his group to the U.S. to service the magazine, as V Design. They went on to continue for 20 years, participating with the magazine.

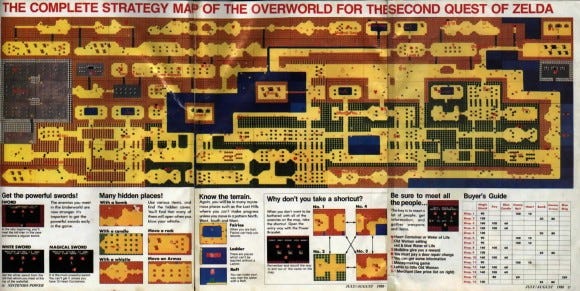

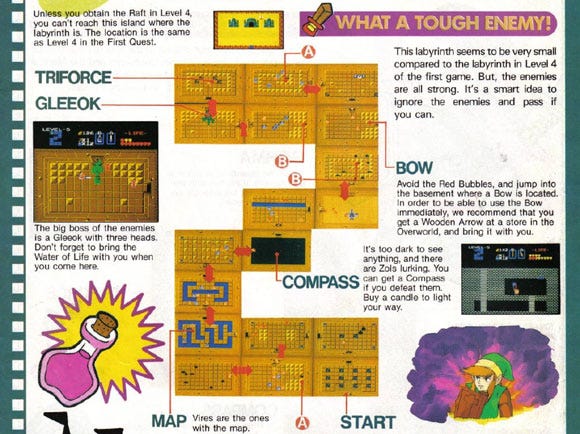

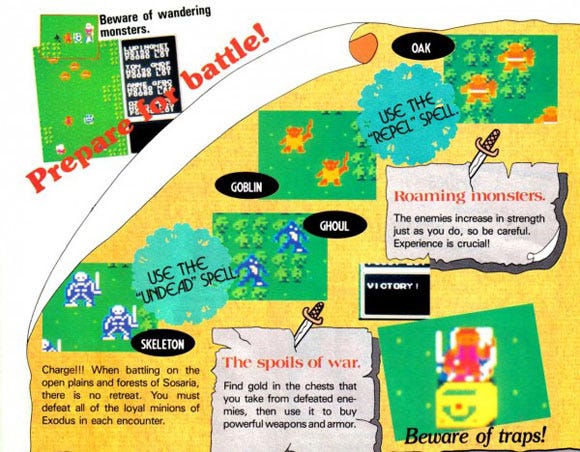

HP: Back then -- it's hard to imagine now, because we have so many tools, including YouTube walkthroughs and so on. It's hard to imagine that we were all playing games on little toilet paper tubes -- this narrow perspective of what the game world was. To have these maps suddenly spoke to how large the game world was, which then resulted in this tremendous feeling of empowerment, because you could feel it, finally. You could finally know what was beyond the edge of your television screen in the next area.

That was huge. I'm just gaga over it now, thinking of how fun it was to pull out a map of Zelda and see the entire world, and be able to go through it with your fingertip and then say, "Okay, there's where you can burn that tree," or push that rock, or whatever. It was so cool. Getting that in the hands of kids was -- from my perspective -- the real big win that we were after.

GT: Especially in the old days, it was really complicated to make those maps. It's not like there's really a "stop frame" button where you can pull a frame and then go to frame two. It's just like a big scrolling thing while you're playing, and where your character is...it's a challenging thing to put all those pieces together.

You have to imagine that you're making a map of Metroid or something. It's extremely complicated to show the multiple layers of the game and the caverns you're ducking into.

HP: That machine that we had at Work House in Tokyo looked like a VCR or something. It was huge. They'd hook it up to the game system, and then it would print out a picture that was maybe four postage stamps big. It wasn't even as large as a Polaroid. It would print out this beautiful color picture, and then these guys would sit there and take their X-Acto knives and cut out the trim, and then they'd paste them onto this larger board, and make this huge board that was the entire map.

There were a lot of bleary-eyed days and nights in small rooms in Japan looking at the big press proofs, and looking at these little TV shots and going, "Is that the third one?" There were a couple of times when the guys pasted them up wrong and connected the map incorrectly. Can you imagine if we'd shipped out something like that? There was lots of that stuff, and things like, "Is it the blue candle or the red candle?" If you made a mistake like that, it could have big ramifications. I spent a lot of energy making sure that was accurate.

It was so, so cool. We had to get that out to the kids.

Click for larger version.

GT: When people talk about why the consumer would just as soon move to digital media or move to the Internet for gaming news, news was never really Nintendo Power's forte. It was really gameplay. Those maps were invaluable. They were definitely what gave the magazine such legs.

GT: Getting it together, we came up with fun concepts. Classified Information would have a background like an envelope and be FBI-ish -- like you were getting all these different codes and passwords, which was an in-thing that you couldn't share over the Internet at the time. It was coveted by fans and they would be excited to get it.

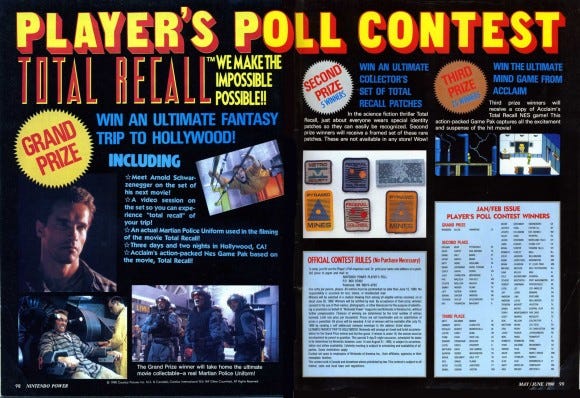

Our reviews were called Video Shorts, and then there were the main features and the maps. With our Player's Polls, the main thing was to gather the information on what games the readers liked the most. It had a bingo card. That was also an idea that came out of Japan. With magazines like Shonen Jump, they include a bingo card every time, and they make decisions based on the popularity among the readership in regards to which anime becomes TV shows. We wanted a bingo card in our magazine in order to monitor the games the consumers were liking, in addition to asking direct marketing and research questions.

Then we always gave away a fantastic prize. It was one of the ways licensees could come up with something and get extra coverage from us for their games. We got these wild things, like a Batmobile, and tickets to the World Series and the Super Bowl and F1 races and meet and greets with Matt Groening from The Simpsons.

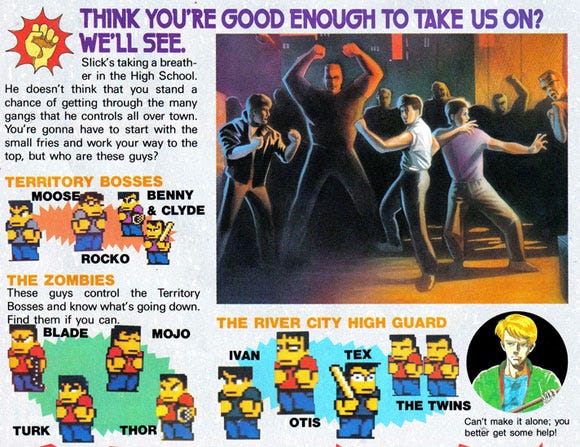

Click for larger version.

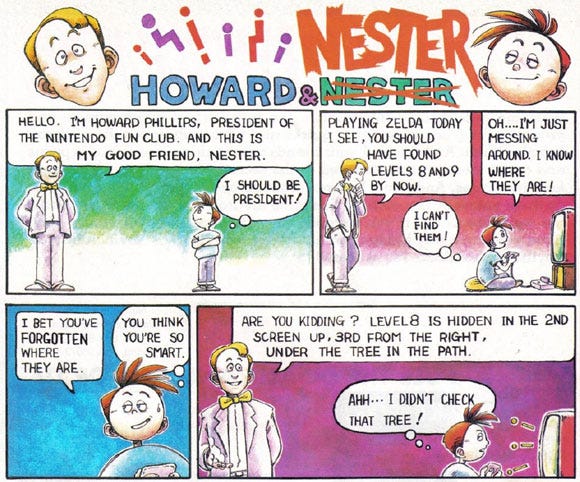

HP: With any game, you have issues where the challenges are too challenging for some part of your audience, and you still want them to have fun. You didn't want them to get blocked. You wanted them to take that 20 percent of the blockers that were blocking 80 percent of the players and get them out in the magazine somehow. That's how we came up with the different mechanisms in the magazine for providing those tips to the kids, whether it's the actual game review or the Howard & Nester comic, or Counselor's Corner, things like that.

It was about how we could come up with different was to provide tips for kids. We wanted them to have fun and not get stopped, but we didn't want them to be calling the 800 number. We knew the 800 number wouldn't last, so we needed to get something in place that they would consider to be better than the 800 number.

GT: Another thing we used the magazine for was in the letters section with customer service. If they had an issue that they wanted covered in the magazine, we didn't want to be writing preachy customer service articles. One solution for that was to present the customer service problem as a letter, and then respond with the answer. That way, it would have been published. That was the way we at Nintendo Power could get around writing consumer service articles.

One time, they wanted to write something about the flashing Control Deck problem. If an NES cartridge wasn't pushed in right, it would flash. I thought I would do my niece, who was 12 at the time, a favor and write the letter from her, because she then would have her name and her city in the magazine. And there was a typo in the magazine, so she wanted to know how to fix her flashing "Control Dick." [laughs] So while I thought I was doing my 12-year-old niece a big favor, it didn't make her any more popular. [laughs]

Other than Howard, we didn't really use pictures of people that we published. We used Nintendo Game Counselors a lot. We had Counselor's Corner, and we would use pictures of them to give gameplay tips.

I don't think anybody wanted somebody who -- and I was around 31 at the time myself -- they didn't want to see a picture of somebody's mom as the person who's doing Nintendo Power. So we were always a little bit...even the pictures of the kids themselves...it wasn't for safety or security so much as you always want the person to put themselves into the magazine, and if you see people who you think aren't like you or don't reflect you, it can be a turn-off. So there were not too many people in the magazine.

HP: I'm not sure if it was Gail or I, so I'll say it was Gail and give her credit for it. It's probably not something in hindsight I would have thought of doing. But it was fun. I remember sitting in a room with Gail and talking about the different ways we were going to provide information to kids to stop them calling the 800 number all the time. You could challenge them with the super-high challenge, or you could provide them tips and tricks and basic stuff, but we didn't want to have 20 pages of tips and tricks. We wanted to have a different feel or flavor to it, to break it up.

Click for larger version.

I was also noticing that a lot of kids -- even moreso today -- are really headstrong and want to do everything themselves. "I knew that. I didn't need any help." That's where the Nester character came from. It's a great foil, someone saying, "I don't need this information, I'll just go and do it."

And then we'd show Nester doing the typical wrong thing that the kids would do, and then give a little story vignette to set that straight in a way that the kids could go, "Oh, cool!" and drop the magazine and go running back to the game because they'd just figured something out. But they didn't actually have to read the tip.

GT: For some reason, when [Howard] met his wife, he said that she liked him in a bow tie, so in 1985, he started wearing a bow tie when we would do PR events. That became the funny character, and then Nester was creating a character out of the name "NES."

HP: Back in that time period -- in the late '70s and early '80s -- it was polyester suits and fat, wide ties. I didn't like them. Everybody tried to be hip with cool clothes, but I worked for several years in the restaurant business and loved servicing people and making people have a great time.

For whatever reason, it would bug me that I had this pendulous piece of cloth hanging around my neck. It was kind of goofy. I guess if you don't think about it, it seems normal, but if you think about it, it's a weird thing that guys go around with a noose of cloth around their neck.

Anyway, a bow tie is nice, tight, close to the neck, and gives you that dress-up look that you need for business. So I wore a bow tie at my wedding, and I wore them for a number of years.

GT: It was just silly, the whole idea -- trying to make something that had a little bit more entertainment value besides wall-to-wall game information. That was probably the silliest thing we ever did.

GT: Game manufacturing was slower then, and of course, when you ship across the water, that's a month. I don't know if you'd call it an advantage, but we had the advantage where when people signed the license agreement and turned in their code for bug checks at NoA, we had pre-negotiated that they knew that Nintendo Power would have access to the code. So we got access to the games internally.

Click for larger version.

HP: I don't know how it is these days, but certainly back then with print, there was this hard and fast, "It has to be done by this date, because that's when thousands of pounds of paper roll into the printing press." That sort of thing.

There were really hard and fast deadlines that we had to meet. So we would pass that information on to whichever source was providing a game, whether it was Miyamoto at Nintendo in Japan or whether it was one of the licensees. They knew when our handoff was.

GT: When someone would call and say, "We have a game coming out!" they'd try and persuade us that the game would be good.

We did have to work closely with them to ensure that we had enough backup material to make the art more interesting, and if there was going to be any kind of promotion or a cover. When we did a poster of the first Batman, Michael Keaton -- or I'd imagine his agent -- thought his face looked too fat, and we had to airbrush his jowls.

HP: All that said, we could turn around pretty quick on a great game. It didn't take a whole lot of time. If you can imagine now, if someone gives you an NES game, you can tell them four hours from now if it was a good game or not. It's not like it takes two weeks to see if a game...or at least, if you can see the forest for the trees, you can look at another tree and tell how tall it is, relative to the forest.

GT: It was a marketing vehicle, but when it was going to become a magazine, the mission statement of the magazine was to help consumers to be more satisfied with their game purchases and ensure the longevity of that category. If you remember, at this time, we still had a concern that people would buy games that they didn't enjoy, and if a family made too many poor purchasing decisions, purchasing products that weren't terrific, then they would walk away from being involved with the NES. The magazine was a component of marketing, but in a customer service way.

HP: I set up and ran the internal evaluation system. Nintendo in Japan was doing something like that to begin with, but we built on that. Initially, it was just myself and another two guys who looked at every single game that was being released in Japan, and we'd all rate them on a standardized form. Then I expanded that to include game counselors, and then expanded it even larger, and brought in kids to fill in forms and say what they liked about different games.

That information is what fed the Power Meter. That wasn't just marketing stuff. The Power Meter was coming directly from that data from people who were playing the games.

GT: Based on that game's ratings, it would help NoA to determine how strong the game was going to be and the way we could support a licensee or development team that had come up with a fantastic game. One of the ways we could do that would be to give them larger coverage in Nintendo Power.

Sometimes they would purchase big licenses or put a lot of energy into a game that just doesn't work out to be very fun or balanced. Those games did not get as much coverage, even if the licensee begged or pleaded. [laughs] The answer was still no. It was considered quite a coup to have your game featured on the cover and to get major editorial coverage.

HP: To this day, my integrity is rock-solid on that. At the time, the hit games were such clear leaders over the other ones, and it was borne out by all the game evaluation data that we got.

We were fed by the scores that were coming out of the game evaluation. We were talking about huge games like Ninja Gaiden and Super Mario and Zelda and Castlevania. They were huge hits.

Occasionally, we'd get a lull where there wasn't a super hit game coming out. A "super hit game" scores above a 32 on a 40 point scale. If there was a game that was a 30 and there was nothing else, that would get the cover, because it was the best game for that period.

Click for larger version.

GT: We sent out 3.2 million [complimentary copies of the first issue], that's how big the database grew from the 600,000 to when the decision was made fairly early 1987.

Our database grew during the time we were pursuing this to more than 10 million. We had a huge direct-response database, and we protected it very closely. We never sold it, and never let the mailing tapes out. For a while, we even directly mailed the magazine in-house and set up a mailing shop because we valued the assets of the list.

When it hit 1.3 million -- and we talked about how fast it grew -- I was looking at what magazines were the biggest magazines in the country, and in fact the biggest one was a senior's magazine. Like an AARP magazine or something. But that's not fair because it's just something you get. It's like AAA Magazine. You get it when you're a AAA person.

I'm really not sure [where Nintendo Power placed, in terms of circulation], but it certainly was up there. Because Nintendo Power didn't accept advertising, we weren't audited, and in order to be formally ranked -- like being a public company or something -- you needed to be audited by one of those companies that keeps track and keeps people honest for ad rates.

HP: It's a lifetime of wonderful memories, working on that thing with Gail and the folks at Work House and at Nintendo and the licensees. It was so much fun. The guys would come in and you'd say you were going to do a feature on them and they just couldn't wait to hop in the airplane and get there and share every possible goodness that they could think of about the game with you, to make sure you get it in the magazine. Without even thinking about it specifically, I smile, and then I think of specifics and smack my forehead with embarrassment or joy or frustration or whatever. It was just all-around great times.

GT: Not to say at the time we thought we were all that, but you know, we just kept going. I just think that now, the sophistication of design and layout is so much easier in a way, and the ability to adjust things and make them look better if you don't like something is...but I don't think so, really. Right now, when I look at it, it doesn't look very organic, and it looks a little unpolished compared to what you might imagine someone would do today.

But kids loved it. They really warmed to it. It felt right.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like