"The traditional approach will try to creep in. [You] need to fight back,” says Supercell CEO Ilkka Paananen. “The interesting thing…is that it gets harder and harder the more successful you are.”

Helsinki, Finland-based Supercell is known for its huge success in the mobile game market, releasing hit games like Clash of Clans, Clash Royale, Boom Beach, and Hay Day. And fiscal 2017 financials finished to the tune of $810 million in profit and $2 billion in revenue.

But that success came about in a way that is different from how most companies operate. Supercell did things “upside-down”—that is, the creative people essentially run the company and management makes sure to get out of their way.

Supercell CEO Ilkka Paananen, after years of working at companies like Digital Chocolate where organizational charts were “right-side up,” theorized that traditional game companies found success not because of their structure, but in spite of it.

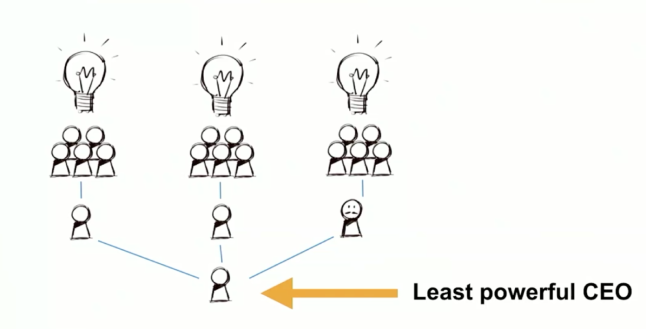

Supercell's model

If you’re unfamiliar with Supercell’s organizational chart, here’s the gist of how it works: teams (“cells”) of 10-17 game developers work on their own respective games.

There is no greenlight process from management, no milestone meetings where teams need to justify their project’s existence to finance. Teams can kill their games and move on if deemed necessary. All creative decisions are up to the teams.

“The idea here is that there is no central process,” Paananen said in a talk at GDC 2018. “Every team can have their own ways of work.” He realized that games that found success under his management at Digital Chocolate were developed by teams that worked particularly well together; they were released exactly at the right time (which is largely based on luck); and, he pointed out: “The less the management…had to do with the game, the better chances of success.”

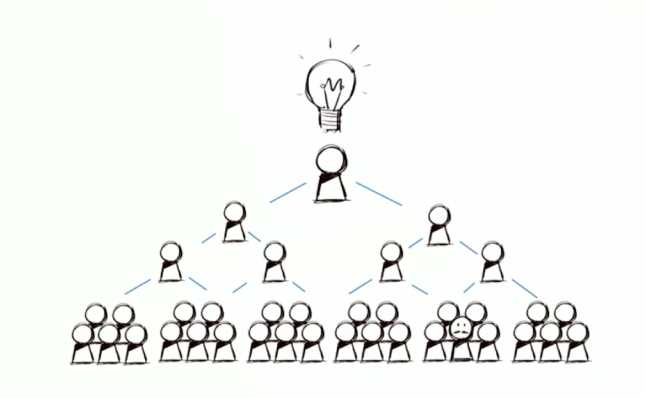

A traditional corporate organizational chart (via GDC Vault)

So the role of management in an upside structure? Build great teams, and support them in their efforts in order to facilitate their success.

It’s a good thing that management gets out of the way in some cases—despite their best intentions, they could snuff out a big success. Paananen said he had doubts about Clash Royale, a Supercell game that went on to be one of the biggest hits not only on mobile, but on any platform.

“I wasn’t a big believer in the original prototype that eventually became Clash Royale,” Paananen said in an interview with Gamasutra. “I was one of the guys who actually woke up quite late and said ‘this is a fantastic game.’ But I try to remind myself why we exist. We’re trying to build this different kind of company.”

"The less the management…had to do with the game, the better chances of success."

Another case of developer-led business decisions comes from Boom Beach, another hit Supercell game that had a lot of doubters, internally.

While it was in development, all of Supercell’s team leads met to talk about the game—and they all wanted to can it, save one person—the lead on Boom Beach.

The team continued to make the game despite the brutal honesty and near-unanimous skepticism about the game. It went on to be a hit.

It’s difficult not to think about what all the other people think when one person says ‘this is how it’s going be.’ For Paananen, even when a vote is as lopsided as it was in the case of Boom Beach, the priority is to preserve the company culture which puts a game’s lead in charge of the decisions pertaining to that game.

“We have these two different paths we can take,” he told us. “One path is where [the majority] can overrule, and just kill a game if nine out of 10 people think it should be killed. And that might be the right call—maybe that would be the best business decision.

"But at the same time, even if it would be the right decision from a business perspective, the price that that we pay is the culture. We wouldn’t be able to say anymore that we have this culture of independence and responsibility.”

The Supercell model (via GDC Vault)

He takes the long view of situations like this: in five to ten years, what matters isn’t that a game was a failure, but that the creators learned lessons, and the culture was preserved so that successes may be had down the line.

Paananen added, “Another path is we let this team do their thing although we don’t believe it will be successful. But at the very least, if they do their thing, they’ll learn. But the most important thing is that we still keep our culture.”

Touko Tahkokallio, game lead on Hay Day, explained in a separate interview that teams are not formed around an idea for game. Putting a strong team together always takes priority. "We get the team together, and make sure they work well together. And then they decide what they want to do. It’s team first, idea second, not the other way around."

"It’s team first, idea second, not the other way around."

Independence and responsibility leads to accountability, and Paananen said that can lead to stressful situations for individuals and teams.

While they can claim the credit for success, they also lay claim to failures. The ensuing pressure is one of the drawbacks of the structure, but that pressure seems to be a natural byproduct of such a model.

Another issue that tough to deal with in the Supercell model, Paananen said, is that due to the small size of the teams, workloads can become overwhelming. Ten to 17 people can only take on so much.

In a company where decisions are made by the creative teams, Paananen admits that there is still sometimes a temptation to do things in the traditional, managerial-centric way, despite Supercell’s success with its current model. For studios that want to try the Supercell model, he said you must resist that temptation.

“The traditional approach will try to creep in. [You] need to fight back every day,” he said. “The interesting thing…is that it gets harder and harder the more successful you are.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like