Fresh off the release of The Room: Old Sins, Fireproof Games' Barry Meade chats with Gamasutra about what the studio has learned in ten years of game dev, and how it stumbled into success on mobile.

At this point, Fireproof Games' Room games seem so entrenched as to almost be part of the foundation of the mobile game market.

But when we caught up with Fireproof cofounder Barry Meade last week, he confessed to something many devs may empathize with: a sense of optimistic nervousness, and concern about whether the studio's latest release (The Room: Old Sins, launched on Friday) would float or founder in the modern game marketplace.

"The game is looking good and everything, but obviously it's a bit of nervousness," says Meade.

Still, the fact that Fireproof is putting out a game in 2018 is itself a notable achievement, given that the studio was formed in 2008 by six members of staff from Criterion Games.

Of course, the team started out as a freelance art studio working on art for titles like LittleBigPlanet and the Killzone series. But by 2012, the team started development on its first game - The Room, which launched that September and went on to both do quite well and influence much mobile game industry.

With the series winning numerous awards, including BAFTAs, Game Developers Choice Awards, and TIGA awards for game design, it's been quite the success story -- and an interesting one for fellow devs to study, given its rather minimalistic approach and low-key pace.

Unraveling the puzzle

A different experience from many other mobile games, each entry in The Room franchise involves solving a series of puzzles, through a series of tactile manipulations, all amongst a very atmospheric storyline. The first game has you opening a number of strange boxes, though later entries move on to encompass entire rooms the player must escape. Throughout that journey, The Room developers embraced touch screen controls in a way that few other mobile devs could match.

"[We] never intended to make a mobile game. It was just that was the only option left to us."

Initially, the idea behind The Room stemmed from financial necessity. The team couldn't afford to make a PC or console game, so they decided to try mobile.

"The way we looked at it, mobile games were...especially coming from people who'd come from the PC and console [field]...they tend to make terrible mobile games or really bad ports or really bad, you know, copies of them," explains Meade.

Noticing the issues, Meade and the team deduced they needed to make a 'proper' mobile game. "It has to be something fit for this piece of hardware, for this audience," he noted.

The thinking was to use the touch interface effectively, and show some 'respect' to the audience. "You know, maybe mobile games deserve to be properly mobile," points out Meade, citing how back in 2012 the idea was that, often, ports would 'do' on smartphones.

Experimentation

The original The Room game came about through experimentation. "It was Mark, our creative director, [who] came up with this idea of, what if we recreated the sort of wooden Chinese and Japanese puzzle boxes that you can buy," explains Meade. "Instead of just having a lock, they might have 10 different things you can do to open it or 100 or 150."

Ten years in, Fireproof has released The Room: Old Sins

The distinctive thing about such puzzle boxes is how beautiful they frequently look and feel. The Fireproof team wanted to capture that feeling in the form of a mobile game. "I particularly remember the old smartphone game Zen Bound...and how lovely that looked," says Meade. "All that game was was rotating a camera around a 3D object, but it was really pleasant and beautiful to look at."

That experience was what Fireproof wanted to build upon. "When we tried it, it just worked immediately," Meade explains enthusiastically. "Like, we whacked up a demo in a matter of two weeks or something like that and it just instantly felt nice and good."

The original plan was to make three prototype games in three months but Puzzle Box (as it was called then) was so good, the third prototype was skipped. Eventually, Puzzle Box would become The Room.

Tactile controls

Throughout, Unity was used to make the franchise. As with the decision to focus on mobile, Meade recalls that the decision to use Unity had less to do with the strengths of the toolset and more to do with finances.

"There's no real sort of great message. [Game design is] just a lot of research at the start. Start off with some ideas. Build them. See how they go and then if they work, continue."

"We had no means otherwise to do it," notes Meade. "[We] never intended to make a mobile game. It was just that was the only option left to us," he concludes. "We don't know anything about it but, like, let's give it a go because it costs next to nothing to make."

Crucial to the series' success was ensuring the experience felt consistently tactile. "It was the marriage of physics to [the visuals]" that achieved that effect, notes Meade.

"The genius part about the touch interface is that anyone...can use it," he adds. "Unlike a console game, where if you hand the joypad to my Mom, she wouldn't even know which way up it goes."

As the team learned, by using the touch interface so fully in the game, "you've automatically wiped out this massive barrier to entry that people have," which they believe led to the series's runaway success.

"We didn't actually have to do much more, but the one thing that we did introduce was physics," explains Meade. "So, the objects that you use in the game, whether you're spinning the camera but also when you're manipulating the objects...they all have a weight attached to them and a physicality, so they've got a momentum and motion." By utilizing such methods, "these things turn what would otherwise be just graphical effects...into something more meaningful."

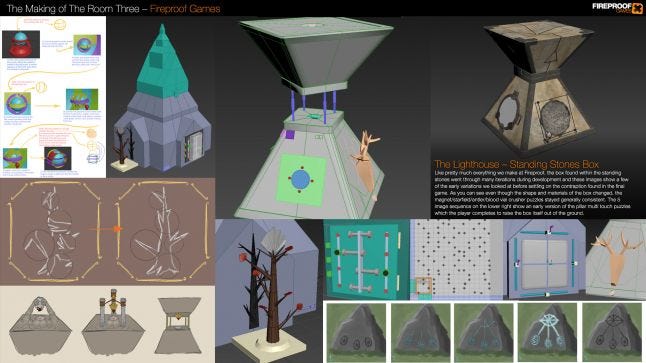

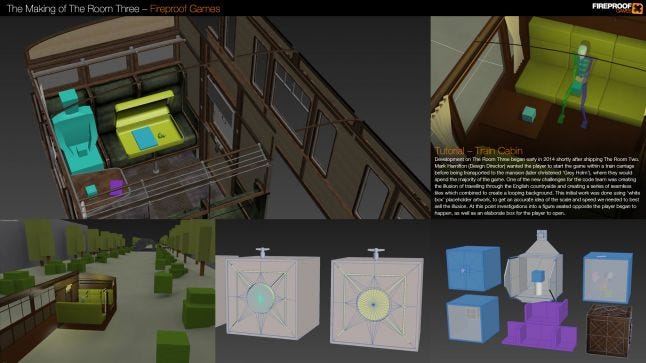

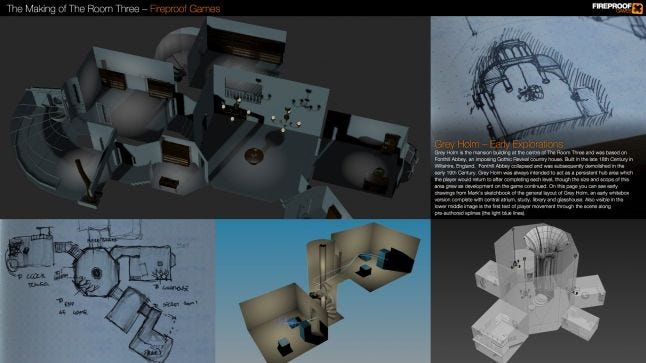

A behind-the-scenes look at the making of The Room 3, available via Fireproof's Flickr

As in life, you're never told this implicitly. "We don't point that out to the player. We don't let them know that 'pieces of metal feel quite chunky and heavy to use'," explains Meade. Instead, the player just does it. "You put it there and people pick up on that and it feels like a type of quality...a type of quality that comes through without ever really knowing it."

Meade is clearly proud of the combination of the team's touch interface and physics engine, and how he feels its 'snappiness' woke people up to this idea of manipulation in a way that 'maybe hadn't been done or concentrated on before'.

Practice and re-iteration

None of that matters if the puzzles aren't up to scratch though. "We really live or die on the puzzles," Meade points out, before explaining how the atmosphere and 'spine tingling' nature of the games also makes a difference. "The puzzle quality has really been the thing that we've tried to maintain and sort of increase over the course of the [series]."

Fireproof uses white-boxing techniques to build everything, focusing on the puzzles before anything else. Rather than just doing concepts, the team uses a more hands-on method of getting started then working on perfecting things further down the line.

"It's a fairly ground up, but practical process," Meade notes. "There's no real sort of great message. It's just a lot of research at the start. Start off with some ideas. Build them. See how they go and then if they work, continue," he explains.

As a production process, it's almost as tactile as the end result. "That's the story of our entire studio...everything we do and exactly how we work," explains Meade proudly, happily noting there's a certain amount of 'going with your gut' and 'winging' it.

While The Room series has managed to get by relatively free of any significant issues arising from the many changes to iOS over the years (outside of updating the games as and when needed) Fireproof did have one unusual learning experience.

The original The Room would only work on the iPhone 4S and above. With no way of telling the difference through the App Store and potentially alienating iPhone 4 owners, the team decided to approach things from a different angle. They released The Room Pocket - a free to try version of The Room that offered an in-app purchase to upgrade to the full release.

"The whole reason for that was so that we didn't rip anyone off," explains Meade. "That they didn't pay the $1.99, download it and then find out [it wouldn't play]."

An unusually charitable move, it paid off. "Right now, it outsells the original Room by quite a mark," says Meade.

What's next?

Four games in, Meade and the Fireproof team aren't certain what's next. "We have not fallen out of love with [The Room] at all," he explains, but there is potential for change.

"The world...is so randomized anyway...it lends itself to lots of different ideas." He points out that lots of games could come out of the IP, but whether they'll be traditional Room games or not, he's not yet certain.

What is certain is that in the space of 5 years, The Room has shaped the landscape of mobile game design. These games have grown into the kind of experience one can show off as a key example of the amalgamation of physics and tactile controls in approachable, intuitive game design.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like