Gamasutra did a livestream chat with the solo developer of the clumsy giant robot game Jettomero: Hero of the Universe. Here are some highlights from the conversation.

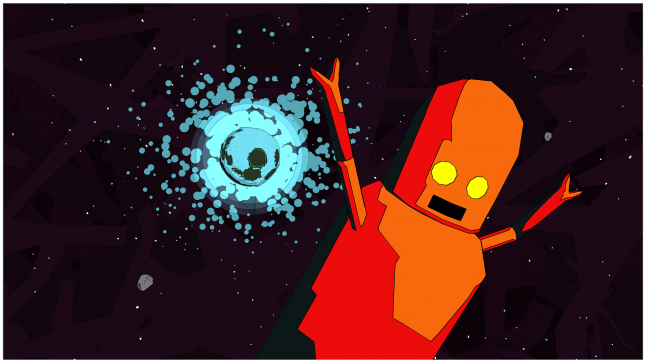

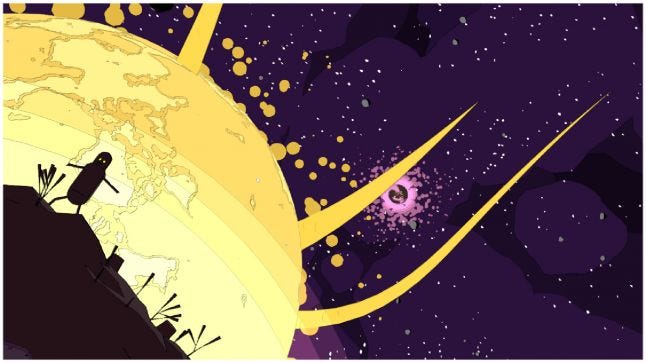

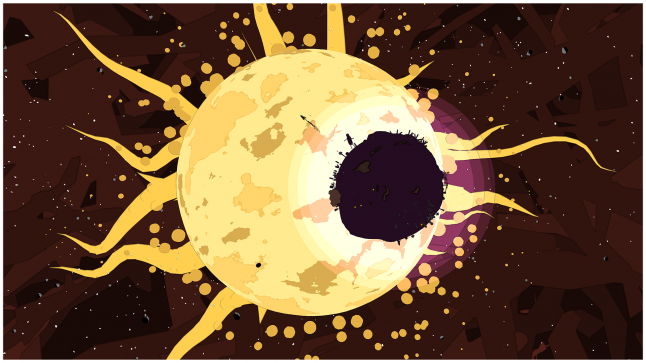

Jettomero: Hero of the Universe, the recent release from Ghost Time Games, is a Noby Noby-inspired game created by Canadian indie developer Gabriel Koenig. It’s a charming, striking game where you control a (clumsy) giant robot hell-bent on saving the Universe (even if it doesn’t need to be saved).

Gamasutra had the pleasure of talking to Koenig about making the game in a recent Twitch stream. Unlike many of the other indie developers we’ve talked to, it’s less a story less about self-imposed crunch, racing to meet a launch date, and more about one man figuring out what his game was while holding down a day job. We've transcribed some of the more interesting passages of the conversation below.

You can watch the stream embedded above, or click here to see it. And for more developer insights, editor roundtables and gameplay commentary, be sure to follow the Gamasutra Twitch channel.

STREAM PARTICIPANTS:

Bryant Francis, editor at Gamasutra

Alex Wawro, editor at Gamasutra

Gabriel Koenig, creator of Jettomero: Hero of the Universe at Ghost Time Games

Using Kickstarter for marketing as an indie

Wawro: You funded this on Kickstarter with a very modest goal, and you surpassed it. It's kind of remarkable. Why did you go to Kickstarter, and what challenges did you find when you finally got your project funded?

Koenig: For this game the Kickstarter was actually really late in the project, I basically had it all done. I think it might have already been approved by Xbox certification, so it was all set it come out.

The two things that I wanted really was money for translations, because the rest of the game development had basically been free, or at least coming out of my own pocket. It was like pay for rent, pay for food, that was the cost of making Jettomero because it was just me doing it.

"I ended up hiring a P.R. company basically the week that I was launching. I was freaking out, I was thinking, 'No one knows about this.'"

Translations were the main financial risk that I needed to take, and especially for launch I wanted to support as many languages as possible, because that's going to be the main push. That felt like it would be a good investment, a good thing to raise money for so I could hit the ground running a little bit better.

The Kickstarter was also largely a marketing push, because no one had really heard of the game before. I had under a thousand people following on Twitter, maybe. I needed to get the word out more and I think Kickstarter is really good for that because it gets shared around, more people see it, and the Kickstarter home page draws in a new audience.

Wawro: Let's talk about marketing as an indie, because this game does feel like it came out at about a busy time of year. It does have such a unique and striking aesthetic, I want to get a sense of how you went about getting out to people. We heard about it from a P.R. agency.

Koenig: I ended up hiring a P.R. company basically the week that I was launching. I was freaking out, I was thinking, "No one knows about this." I used someone who knows how to get this in front of people a little bit better than I do, because otherwise it could just fall flat. That was another investment that I made. It's a difficult game to market.

"Sales-wise it's not helped so much yet, but in terms of exposure Kickstarter have done a good job of getting it out in front of people like you and a bunch of news sites.I don't think I would of had nearly as much coverage without them."

Wawro: Now that we're past, I don't want to say the height, but it was almost like there was a certain golden age on Kickstarter, where there was a bunch of attention and press around it, and now there's so many games out there that that has ceased to cut through the noise the way it used to.

I think a lot of indies are looking back at P.R. teams and asking, "What can they do for me?" Clearly they got our attention. Other than that, has that route paid off for you as a developer, or are you not really sure yet?

Koenig: Sales-wise it's not so much yet, but in terms of exposure I they've done a good job of getting it out in front of people like you and a bunch of news sites, because I don't think I would of had nearly as much coverage without them. And also the YouTube players, they got to them way more than I would have otherwise.

Wawro: Yeah, so how did that go? Did you reach out to certain YouTubers, did you just throw out key indiscriminately, was there a certain audience you were trying to get this game in front of at all?

Koenig: I think I did a bad job of that. I emailed a couple of influencers, and then once the game came out I started getting emails from people and I had to filter through all of them because I can't give the game away to everyone. I definitely got a couple of larger streamers who got in contact with me.

I also signed up for Keymailer, which is a good site because you just add keys for your game, and then anyone who has a verified account for streaming or YouTube can link up and request keys through that. So it's easy for me to say, you have this many followers, you have this many subscribers, here's a free copy. That was a really useful tool for me to get the game out in front of people who could play it and influence an audience.

Using comics to influence art

Francis: What do you think makes good comics, and what can games learn from them?

"Jack Kirby and 1970's sci-fi comics, that was where I drew a lot of stuff from."

Koenig: I collected comics for several years, and I was kind of one of those superhero people, like those people who read Spider-Man and Fantastic Four and stuff like that, but there were certain books.

I picked up a Hellboy book one time, and that was like, this is the coolest comic that I've ever seen before. Just seeing the books more as a form of art, and not just conveying story and action, was an inspiration.

And also, stuff from the Seventies was really vibrant, and surreal and abstract, but also because space is also kind of weird, and you don't know what's in space exactly, so it's easier to imagine these strange designs and patterns. I haven't read much stuff from the Seventies, but just doing Google searches all the time, for Jack Kirby and 1970's sci-fi comics, that was where I drew a lot of stuff from.

"I made like 20 pages of comic, that is just using screenshots, and afterwards moving them into panels and adding text. That was really cool, taking the game and reformatting it into something completely different, and it worked pretty well."

Francis: Yeah, I'm sure I'll get flak for this, but what attracts me to comic books and graphic novels, the medium, is less often the writing and more often the art.

There's a lot of interesting storylines there, and ways of expressing characters, but really when you come right down to it, it's stuff like this, striking stuff that leaps off the page. Stuff that grabs you and makes your imagination explode. Like a chubby robot taking off from a planet. (laughs)

Koenig: Yeah, for the Kickstarter, I realized, I should do a comic book using the game. So I made like 20 pages of comic, that is just using screenshots, and afterwards moving them into panels and adding text.

That was really cool, taking the game and reformatting it into something completely different, and it worked pretty well as that kind of comic book.

Wawro: Yeah, it's neat! Not a lot of devs play with the medium in this way. Not to say that they can't, but this game, this project seems uniquely suited to making mock comic strips and putting art on gallery walls. That's the kind of stuff that you could do, but it would be harder, with a white-boxed 3D puzzle-platformer level.

Indie labor-sharing

Wawro: Gabriel, the one part of this project that it sounds like you didn't do yourself was the audio, right? You had friends help with that, it sounds like it was a barter thing, you helped them out with something?

Koenig: Yeah, I still owe them some work. We basically made it a case-free interaction, just exchange of labor.

Wawro: How did that come about? Everything I'm hearing from you is that you love making things, you love games, you like Unity, you basically taught yourself everything to make this game. Why did you shy away from audio? Why did you feel compelled to reach out to another, more expert, source when it came to sound?

"The game didn't need to be just me, it ended up being that way because it's hard to find people who are going to do this stuff for you, and so once we got that labor exchange worked out it was kind of the perfect solution."

Koenig: It's funny, because my background is sound design! I think that maybe, with that background, I knew that I wouldn't have the time and full focus to really give it the treatment that I wanted it to have. There are a lot of sounds that I did that are still in there, but there was just too much stuff, and I realized I didn't have all the tools I needed to get it done the way I needed to.

I can't remember how I started talking with Gordon, but we're big fans of each other, and we started talking like, if you wanted to do some programming for me, we could do some sounds for you, and I thought that would be perfect, because then I don't have to worry about this part of development.

The game didn't need to be just me, it ended up being that way because it's hard to find people who are going to do this stuff for you, and so once we got that labor exchange worked out it was kind of the perfect solution.

I recommend that to any indie looking to get help in certain elements. Like, you might not have the budget for it, but you do have the skills to help someone else with stuff, and that's huge, you can both get things done that would otherwise cost you a lot more.

Wawro: You did have the benefits of networking with colleagues, even though it's not the traditional Go-To-A-Game-Dev-Meetup and then meet folks. This may be a weird thing to answer, but how did you know that that was the right thing to reach out to somebody else for, and everything else was something you could do on your own, or did it just end up that way, where you made everything, and then you decided to reach out for sound help.

Koenig Yeah, it was kind of incidental. It might have been Gordon who proposed it to me. I was asking people on Twitter if they wanted to do any models for me, I think, in a labor exchange. I wanted help with the monsters, because that was another thing, I don't have the time to give this proper justice, and I found one guy, who ended up doing concept sketches of all the monsters.

I based all the models off of that, which was super-helpful, because it was a different look, and I always find that if someone else does something then I like it more. You become really critical of your own work, and having someone else's contribution distances you from it, in a good way, so that you can say "That's really cool." You don't become self-critical about it.

Wawro: Yeah, I think you're right, and I'm glad you mentioned it because it's very tempting, standing on the outside, to say, "Oh, you reached out on the sound portion because that's what you know best, is sound, and so you know best how bad it could be?"

Where if you were just teaching yourself to code physics setups and graphics filters and stuff, you don't know how bad that could go or how hard it could be until you're right in the middle of it.

Koenig: Yeah! (laughs)

For more developer insights, editor roundtables and gameplay commentary, be sure to follow the Gamasutra Twitch channel.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like