Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

A summary of the law that allows artists, including game devs, to reference trademarked titles in their works.

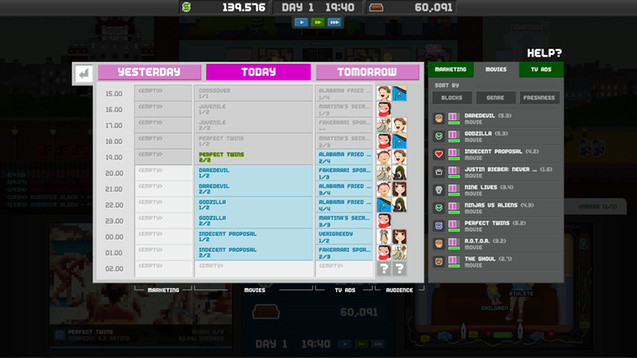

I originally wrote this post for a client's dev blog to explain a common question about their game, Empire TV Tycoon, which made frequent reference to popular movie and television titles. It is republished with permission.

Trademarks are an important form of intellectual property for any business, and doubly so in the entertainment business. Take the film industry, where a good film title can stand out and create strong associations in the public’s mind. Such trademarks tend to be jealously guarded, so it is easy to be confused when a game like Empire TV makes such extensive use of movie and television titles. In this post I will explain how the courts have balanced trademark protections against considerations of free expression and why Empire TV is able to reference trademarked movie titles as it does.

The first question to ask is whether the title is trademarked at all. There is a general prohibition on trademarking the titles of single works. This rule does not apply to a series however. So The Martian cannot be trademarked, but Harry Potter certainly can be and is. Of course, it isn't the end of the world just because a title is trademarked.

In the United States, federal trademark protection as established by the Lanham Act seeks to protect consumers by avoiding confusion over the source of a good or service. If a business establishes a trademark, only that business is allowed to use it. If another business were to do so then consumers would become confused over the source of the product or service. That is the entire theoretical basis of trademark law.

However, the Lanham Act is not absolute. There are other important considerations at play when artistic expression is involved, namely the First Amendment guarantee of free speech. It would be unconstitutional for trademark law were to stifle free speech and free expression, so courts have come up with a legal “test” to balance two important legal goals: consumer protection under trademark and free expression under the First Amendment. That formula is called the Rogers test.

The Rogers test traces back to an important Court of Appeals case (that’s one level below the Supreme Court) called Rogers v. Grimaldi. The Rogers of Rogers v. Grimaldi was Ginger Rogers, the famed dance partner of Fred Astaire. It is said that Ginger could do everything Fred did, only backwards and in high heels, and she became rightly famous for it. I won’t go too deep into the details, but the case involved an Italian film about a different pair of dancers and was titled “Ginger and Fred.” When Rogers sued for trademark infringement, the court recognized that it had to accommodate free expression in trademark law.

The Rogers test accommodates free expression within trademark law by guaranteeing that an artistic work can reference a trademark unless “the title has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever,” or it “explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.”[1] So, as long as an artistic work does not use a trademark in a way that has no artistic relevance and it is not misleading, that artistic work is protected from a trademark claim. This rule has been widely followed and adopted in other courts.[2]

Now consider Empire TV. Thanks to the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association we know that video games are consider expressive works. Therefore the question is whether the game’s use of trademarked titles complies with the Rogers test. As the very purpose of the game is to select programing for a television station, referencing the names of programs by their title is directly relevant to the game’s art. This satisfies the first part of the test. Further, nothing in the game would mislead the player about the source of content or work. Playing as a TV executive who schedules Alien vs. Predator does not lead the player to assume that the game was made by 20th Century Fox. Thus, Empire TV passes both prongs of the Rogers test, and its use of trademarked movie titles is protected by the First Amendment. Chalk one up for free speech!

[1] Rogers v. Grimaldi 875 F.2d 994, 999 (2d Cir. N.Y. 1989)

[2] See e.g. Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, 296 F.3d 894, 902 (9th Cir. 2002) (“We agree with the Second Circuit's analysis and adopt the Rogers standard as our own.”)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like