Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

A field experiment where researchers acted as a male or female player in an FPS. The players spoke positively, negatively or did not spoke during a match. After the match, researchers sent friend requests to all players. The rate differs across factors.

Cross-posted from my blog at VG Researcher.

Previously in communication science, Kuznekoff & Rose (2013) did a field experiment in a popular FPS where they played either as a male or female player and analyzed comments directed towards them. What they found is that the female player received three times as many negative comments as the male player.

Adrienne Holz Ivory (Virginia Tech), Jesse Fox (Ohio State University), Frank Waddell (Pennsylvania State University) and James Ivory (Virginia Tech) conducted a field experiment of their own where they examined how players of a different FPS game reacted to either a male’s or female’s friend request following a match. What did they found in this field experiment?

Abstract

Sex role stereotyping by players in first-person shooter games and other online gaming environments may encourage a social environment that marginalizes and alienates female players. Consistent with the social identity model of deindividuation effects (SIDE), the anonymity of online games may engender endorsement of group-consistent attitudes and amplification of social stereotyping, such as the adherence to gender norms predicted by expectations states theory. A 2 × 3 × 2 virtual field experiment (N = 520) in an online first-person shooter video game examined effects of a confederate players’ sex, communication style, and skill on players’ compliance with subsequent online friend requests. We found support for the hypothesis that, in general, women would gain more compliance with friend requests than men. We also found support for the hypothesis that women making positive utterances would gain more compliance with friend requests than women making negative utterances, whereas men making negative utterances would gain more compliance with friend requests than men making positive utterances. The hypothesis that player skill (i.e., game scores) would predict compliance with friend requests was not supported. Implications for male and female game players and computer-mediated communication in online gaming environments are discussed.

The adage “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” reflected an idea in the early days of the internet that anyone is free from their ties to the real world, that the virtual space is leveling ground for everyone. Anyone can explore their identities. Unfortunately, everyone brought their real life baggage into that space, and relevant to this study are gender stereotypes.

In an online environment, users interact with each other not from a linguistic blank slate, but with what they have. From these interactions, they form impressions on whatever information presented to them and evaluate such information with their knowledge, including stereotypes. There are linguistic differences between men and women in online interactions where men communicate assertively and use crude language, for example, whereas women tend to communicate empathetically. These differences would affect others’ reactions when they become aware of a user’s gender, in which one type of reaction is sending sexual messages to female users.

The amount of identifying information online is comparatively limited to the real world. We don’t see them, hear them, etc. Our anonymity makes us more stranger than strangers in real life. This works both ways, for the “speaker” and “listener”. According to the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation effects, our anonymity deindividuated us and as such we rely on outside cues, we rely on others to guide us on how to behave and think. We rely more strongly to those whom we identify with, an in-group, so a male player would behave like other male players he observes because they share an identity. With that in mind, he would act upon on more generalized and abstract information, that is stereotypes where we have an idea of a typical/idealized person belonging to a group. So, imagine what your typical male or female gamer, FPS or Starcraft player would be like. We would take on that mask and perform it online.

In terms of how a female or male user interact, the Expectation States Theory can explain how people would infer and anticipate what other users would behave. More precisely, what users anticipate how a male or female user should or should not behave and how users would treat them. Because of the deindividuated nature of online gaming, stereotypes effect is arguably more stronger and gender more salient. The videogame social environment is quite masculine, therefore male players would behave and expect very masculine social interactions and the opposite is true for female players, they should behave submissively or what they think women ought to be. Should a female player violate these expectations by asserting herself, social punishments ensue such as questioning her legitimacy and competence as a gamer . Should a male player violate their masculine expectations, well other men will denigrate their manhood and competence.

The FPS genre is also a competitive environment and a place where a show of skill should attract fame, respect and glory. IMO, it sounds like an egalitarian argument is that players earn respect and friendship through a show of competence and merit, this argument avoids downgrading women from earning respect. However, given what we learned from expectation state theory and the deindividuation effects on gender stereotypes, is the meritocratic argument of competitive gaming true? Does a competent female player earn their fellow gamers respect or shall it be another shout for a sandwich?

On a tangent, Allison Eden (VU Amsterdam) started this trend at looking the role of game skill in a 2010 study. It does make intuitive sense that in a social milieu where competition is salient, you’d look for relevant things in there like gaming skill or kill/death ratio that some players in certain games seemed to make huge deal out of it. These attractive and intuitive metrics is what is thought to have gained famous players their fame, recognition, and friendship. But, this is common sense thinking and this could blind us from something more obvious. I had a conversation with Jesse Fox months ago, but I forgot the insights from it, something about streaming gamers, and about other factors, such as sociability, friendliness, that makes streamers more popular than others. Asking interpersonal communication scholars about relationship formation or asking players how and who they would friend request. Edit: one factor was the study could not control for the other players’ skill, it is possible that players tend to friend requests others of similar skill.

Method

It’s a field experiment. They went online to play matches with other players on the Playstation Network through the Playstation 3 in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3. They played deathmatches using automatch where they can play with up to 8 other random players. The matches last 10 minutes or until one player reaches 30 kills which ends the match.

There are 3 experimental factors:

Gender: They created two Playstation Network accounts with gendered user names. The female user was named “Ashley” followed by several numbers. The male user was named “John” followed by several numbers. They use the same character in every matches (e.g. Russian Spetsnaz rifleman, U.S. Special Forces sniper, African Militia light machine gunner).

Utterance type: They had recorded voice chat utterances for each gender, this is to standardize voice chat in all of the matches. What they seek is how other players react to the voice and the type of utterances. To this effect, they have three types of utterances: positive, negative and no utterances. The positive utterances are phrases like “nice shot”. The negative utterances are phrases like “you suck”. There are no mixing utterance types or any sort of dynamics, like reacting to positive or negative utterances from other players. Try planning that. They uttered at 90 seconds interval during matches.

Player skill: Good or bad. The experimenter is an experienced FPS player, so in the good condition, he just played normally. In the bad condition, he played with weapons that are difficult to use. This method worked as the average kill/death ratio in the good condition is 1.2 (SD=.51) and .42 (SD = .19) in the bad condition.

Dependent variable: The friend request. The authors were pretty strict and detailed about the friend request. First, they initiate the request immediately after the end of the match, and to all players that were in that match. Second, they count responses as either accept, deny or no-response. The no-response is counted if the player did not respond within the time of a match (i.e. 10 minutes) after the request. The no-response would not be used in the analysis because there are many unknowns to make any meaningful inferences, it is possible they were busy, they logged off, ignored the request, don’t speak English, etc. Even if they responded after 10 minutes, it makes you wonder why they took that long, again this is an uncertainty. Furthermore, the authors imposed this time limit in order for the experimental variables to be as salient as possible because a delayed reply may mean a lot of things that may not be relevant to the variables of interest.

With these experimental conditions set, they recorded 238 online games with a total of 1371 unique participants, 520 of whom responded within the time limit. No information were asked from the participants, so no way of knowing their gender or age. But we can make some statistical assumptions that most CoD players are young men.

Results

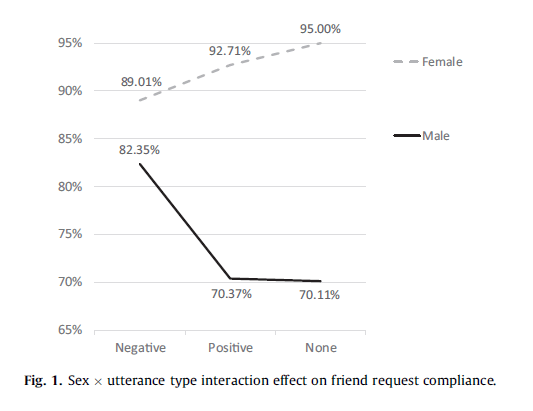

The analysis is based from the 520 participants who responded. The following graph depicts the likelihood of participants accepting the friend request. The statistical significance is true between gender, women do get more acceptances than men. The statistical significance between utterance type is true, men who utter negatively tend to get more acceptances than those who uttered positively or were quiet whereas women who were quiet tend to get more acceptances than those who uttered positively or negatively.

There were no statistical significance about player skill having any bearing on friend requests.

Discussion

The take home message is that female players who sent out friend requests have a greater chance of being accepted than male players do. Furthermore, the chances of acceptance differs based on how the player spoke in the game, and congruence with gender stereotypes. Male players who spoke negatively or trash talk in the game and female players who were silent or meek have the greatest chances in getting their friend request accepted. In a way, men and women are treated differently in gaming. On a tangent, I wonder if this is similar to statistics on online dating’s messaging and reply rates.

Why are there differences in acceptance rates between gender and utterance types? As predicted by Expectation States Theory with the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation effects, male and female players who do not violate gender stereotypes are more accepted by other players. Since there is so little identifying information, you could say that people would imagine what others look like, starting with stereotypes. The negative utterances from the male player would suggest that other players saw it as normative behaviours for a stereotypical male player. I recall an argument that trash talking is a character defining trait, pumps up the excitement and that this is how gamers should behave. Somewhat blind to the point that this is how men should behave.

The authors discussed the significance of social networks within a masculine social space that we call videogames. A male player accepting a female player as one of their friends can signify to others that they are sexually attractive and popular (from their point of view). This is one way that reinforces behaviours and stereotyped perceptions of female gamers, as a result male gamers would pay a lot more attention to female gamers, and good deal of misunderstanding ensue, friendly acts by female players may be misconstrued as sexual. The gender differences in friend request acceptance corroborates the anecdotes that female players receive many random friend requests from male strangers once their gender is revealed or inferred as some male players may be mistaken for a woman.

I emailed one of the authors for further thoughts. The author shared their thoughts regarding the skill factor. The high versus low skill conditions was successful in terms of kill/death ratio, it may not have been noticeable enough for others. They surmised that match ranking might be a factor, for a player to consistently rank in 2nd or 3rd, as opposed to 1st, may not get a lot of attention among a group of players. They pointed out skill levels in two-player co-op studies have significant effects. But, “Of course, the likely possibility that skill wasn’t obvious enough in its manipulation to have effects only points back to how pronounced the effects of other, similarly nuanced manipulations where, such as just using a male name or saying a few phrases on the voice chat channel.” I recalled that skill might be “threatening” to other players where a player might accuse another for being a cheater or hacker. At this point, it is rather difficult to assess skill level alone in a group setting.

They offered another comment relevant to the field: “While a lot of the more dramatic speculated effects of video games, such as disputed social effects of violent content, have received a lot more attention from researchers and the public, studies like this make me more and more disappointed that we don’t pay more attention to the subtle dynamics of online interactions that may have lasting social consequences. It really disappointed me to find that even in a game where you pretend to be a soldier running around shooting at people, there appear to be gendered expectations about how to interact with others, and that worries me more than the fact that they’re carrying pretend guns around.”

The sessions were recorded for record-keeping to ensure data quality for the study. They have not looked into the recordings as of yet. They did note that some players sent unsolicited messages to the female player.

The authors suggested some future field studies to consider. One consideration is the possibility of obtaining some demographic information. Another consideration is how would players react to players of different ethnicities, sexual orientations and age? One of my own considerations is how do players initiate friend requests, such as their motives, who they friend, and under what circumstances. Actually, why not share your thoughts in the comments section.

The following is another field experiment that was presented at the International Communication Association’s Annual Conference of 2014. The title of the poster is: “Harsh Words and Deeds: Content Analyses of Offensive User Behavior in Online First-Person Shooter Games“

They fielded undergraduate students in two separate studies to play in popular FPS games, Call of Duty: Black Ops I & II (PS3 & Xbox 360) and Halo:Reach. In total, they recorded 42 hours of gameplay.

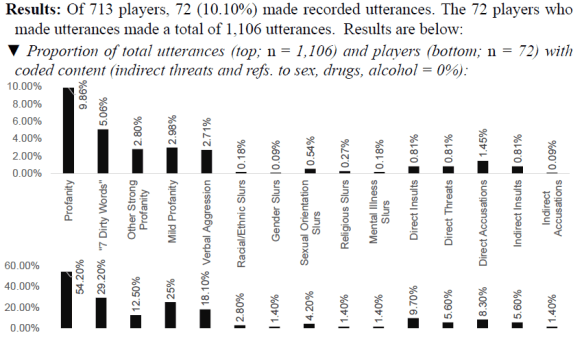

Utterance types: Study 1: they examined voice chats in Halo:Reach and Call of Duty: Black Ops. Across 89 matches and among the 713 players identified, 72 of them uttered. They categorized only negative utterances. Here is a graph of their results.

An example interpretation is that profanity accounted for 9.86% (or 109) of total utterances, among the 72 who uttered, 54% of them did so.

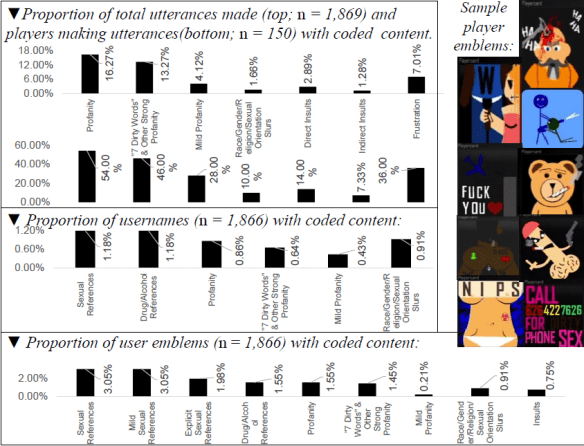

Study 2: They examined Black Ops II players’ profiles and utterances. Across 172 matches and among 1866 players, 150 of them uttered.

There is a minority of players who use voice chat and they commonly do so negatively. Similarly, there is a minority of players who expressed themselves in an offensive manner in their player emblems and profile names. Although, the numbers are kept low because they may get reported by other players or banned by administrators for violations of the terms of services. It makes me wonder about the proportions in an unregulated gaming environment. These results sounded like what Jeffrey Lin of Riot Games have found, a minority of toxic players and a majority of good players. Although a single chance encounter with these toxic players and toxic interactions are relatively rare, but they are common enough over time. With these results and some upcoming data, we have increasing support and clearer ideas on approaching negative online gaming interactions. This leads to some research questions: who are these toxic players? Where do they come from, in terms of social, cultural and economic status? What are their motives, attitudes and beliefs in gaming and in general? Do they express the same way in real life? They do express themselves consistently or did they, as Lin argued, had a bad day?

Holz Ivory, A., Fox, J., Franklin Waddell, T., & Ivory, J. D. (2014). Sex role stereotyping is hard to kill: A field experiment measuring social responses to user characteristics and behavior in an online multiplayer first-person shooter game. Computers in Human Behavior, 35 , 148-156. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.026

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like