Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Beacon Pines' branching narrative makes the most out of dramatic irony.

Branching narrative can be a double-edged sword in narrative design. On the one hand, being able to track player choice means you can deliver interesting narrative payoffs that reflect the journey they've set out on.

On the other hand, branching narrative can be a production nightmare, as a scaling number of player choices can give birth to tertiary problems across development. And then there's the nagging question all narrative designers face: are these different narrative pathways worth it? Will the player feel rewarded if they play again and take a different path?

If you need to spice up your narrative branching, drop everything you're doing and go play Beacon Pines. This tiny game from Hiding Spot Games has some of the best branching narrative I've seen in eons, especially from a small developer.

The secret ingredient? Dramatic irony. While you wait for the game to download (if you aren't getting it right now, what are you doing?) let's discuss why this age-old writing tool works so well in Beacon Pines.

What is dramatic irony good for?

In case you slept through 11th grade English class, dramatic irony is the literary idea of giving the audience narrative information that the characters don't have. It's primarily a great tool for raising tension, but it can also be used to sell tragedy, loss, longing, and more.

I don't want to spoil Beacon Pines right off the bat, so let's go to The Bard for an example. In Shakespeare's Comedy of Errors, the audience is immediately introduced to the fact that two pairs of separated twins have arrived int he same city. Shenanigans ensue, but the characters don't have any idea what's going on until the back end of the third act.

Shakespeare milked this theatrical conceit for the sake of comedy, but he also got plenty of tension out of it. Sometimes a problem would be solved if characters knew about the "surprise twins" situation, but other times they would be in more peril if that were apparent. He weaves the coincidences back and forth to tell one of my favorite stage comedies.

No characters remember what happens down the other branches of this story.

Plenty of games make use of dramatic irony too, but it's usually delivered through cutscenes. Players might get a cutaway where they learn the villain is setting up a trap for our heroes, or maybe a game like Devil May Cry 5 will portray different groups of heroes who think they're at odds but are really working toward the same goal.

Beacon Pines does something novel: it bakes the dramatic irony into the branching narrative, and sends players back up the path with new insight about its characters—none of whom are ever aware that they're in a branching narrative story at all.

Beacon Pines wants you to explore all choices

If you've played BioWare's Mass Effect trilogy, there's decent odds that you haven't seen the wide array of story possibilities that can pop up by the end of the third game. By the time you finish Beacon Pines, you'll have seen most ways that the story might play out.

That's because Hiding Spot Games does something really smart with this game: they let some branches of the story cut off early, but makes sure every side story shines an interesting light on its characters.

In Beacon Pines, you play as Luka—or maybe, not entirely Luka. You're technically "yourself," helping an unnamed talking book (who doubles as the narrator) find a happy ending for Luka and those around him. Luka is a tragic tween with one dead parent and another missing, being raised by his grandmother in a small town with a dozen dark secrets.

The vibes are a bit Twin Peaks, a bit of Amblin-style "kids on bikes," and a bit of Redwall all in the mix. The dialogue is terrifically authentic, with the cast of savvy kids given as much pathos and wit as any of the adult characters.

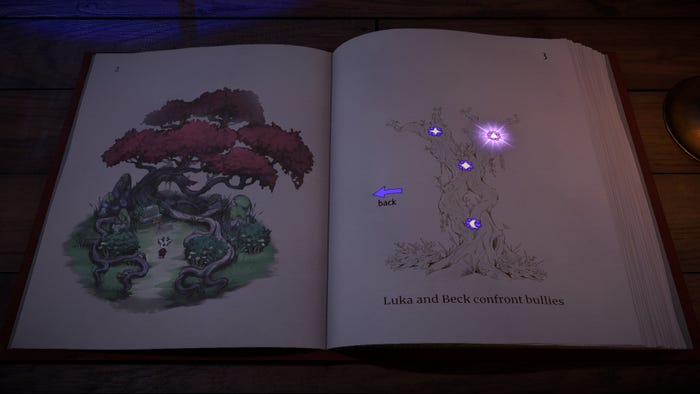

On the first day of the story, Luka and his pal Rollo investigate a seemingly abandoned warehouse bustling with activity. In one of the game's early branching moments, players are given a chance to confront a mysterious figure in a hazmat suit, or hide from him. One path ends in immediate failure, the other continues the story down another branch.

Things can go south here real fast.

Right away, Beacon Pines uses this to amplify the stakes. Players are briefly railroaded here into the "bad" ending, so the book can explain why it's looking for a good one. And the game doesn't pull its punches. Even though Luka is a child, the "bad endings" of this game are all heavy as hell. The implications often imply he and his friends are physically harmed, locked up, or worse.

So after watching Luka meet a terrible fate, players jump onto another narrative path—one where Luka doesn't necessarily have any context of the dark end that waited him. The players know Luka's life was in danger, but he doesn't.

That's one of the early, simple examples. As the game progresses, Beacon Pines doles out secrets about its different characters and the game's world. But every time the branch ends in a dark place, players take that knowledge back into the other plot threads, giving them context for certain decisions, or how the town's colorful cast of weirdos is behaving.

The finale of the game really exploits this for all its worth, cursing the player with knowledge about the motives of one character...but leaving Luka blissfully unaware, trundling along as a dark threat walks right alongside them.

It's moments like these that let the game have its cake and eat it too—it can balance cute, earnest moments with its cast of kids with darkness and horror. If that was all Beacon Pines did with its dramatic irony, that would be praiseworthy enough.

But there's so much more!

Beacon Pines is a game about feelings

Luka, Rollo, and their new friend Beck are all pre-teens with a lot of baggage. Luka's parents are out of the picture. Rollo's family is hard on him and treat him with excessive discipline. And Beck is dealing with the pain of moving to a new town, and under pressure as her parents fight about the reasons for moving.

Beacon Pines uses the many branches of its tree to explore how these different traumas intersect with and diverge from each other. It even takes time to dive into the psyches of other characters, like the town bully, Luka's grandmother, a drug store owner, and more. The characters may all be anthropomorphized animals, but their pain is so human.

Most games don't have the time to drop everything and let their characters literally just scream into the night about how angry and upset they are. Beacon Pines builds out a whole branch for Luka to do just that—and it's a particularly painful branch, since the choice to stay at home with Beck in the rain puts him in a fight with Rollo.

This choice has a heavy payoff.

In the timelines that don't end in tragedy, Luka doesn't remember those moments. His friends don't either. One of Luka's peers (a bratty bully named Iggy) is given a surprising amount of depth and has to deal with a surprising amount of physical torture in one set of branches. But in the "happy ending," he just kind of wanders into the finale as a smug compatriot.

Neither Iggy nor any other supporting cast members have any idea that someone's learned their deepest darkest secrets—but you, the book (and maybe one other character) all do.

This kind of branching narrative is brilliant. It's innovative, impactful, and elevates Beacon Pines into the pantheon of great interactive storytelling. The final product is like a really savvy middle-grade book—a story about kids, change, and growing up that's accessible to younger audiences but sensitive enough to tackle evocative themes.

If you're going give players a wide variety of choices in an interactive story, why not reward them for exploring every possible path? Beacon Pines does, and in a few years, I hope developers who've played it will be able to take inspiration to sharpen their own stories too.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like