Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

How our thinking works when putting the thoughts into play towards the desired goal in the making of an engaging and dynamic game system.

This post originates from the site Narrative Construction and is part of more than a one-year-long project which goal is to explain from a cognitive and narrative perspective the mind and hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system. With help from cognition-based models, the focus is on the opportunity to explore how our thinking, learning, emotions work when setting out from scratch towards the desired goal.

The title “Putting into play” is inspired by the term mise-en-scene, which means, “putting into the scene” (or “put on stage”). The term had its origin in theater and was later picked up by film scholars to have a way of referring to the practice of directing, planning and controlling the elements for the desired effect on a stage or in a frame of a film. Since the term isn´t established in games but where the concept could provide an overlook of the stylistic elements that are to be organized and arranged in the creation of a form; my intention is not to put a new term into play. What I will “put into play” are the thoughts that precede the choice of elements that are to become the parts of the desired form of an engaging and dynamic game system.

A shift in approach

This isn´t the first time I´m propelling thoughts as a means to show how the initial thoughts matter to the construction of a concept. But what differs “Putting into play” from the former twenty-four posts, where I have used propellors, radiators, grandmothers, contract killers, Cinderella´s shoe, and even Walter White´s underwear as a means to describe the narrative from a cognitive perspective in construction of an experience, is that I will, from now, leave the old analogies. The cause is due to a 7-grade model of causal thinking (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017) that explains how our thinking and understanding works, or as to be more precise, it shows what is going on "inside our heads", which make us act and react. So from now on, due to the shift in approach:

I will assume that every one conceives the narrative and gameplay as integrated entities. As a majority of game makers are already working consciously with the merging of the two entities, I will focus on the making of the game and the knowing why and if an element is needed, as to do what, in the construction of experience.

I will assume everyone is positioned beyond structures, templates, genres, and conventions, to build them rather than build upon them.

I will continue to use the term narrative construction as to allude to the involvement of putting the pieces of information “into play” that creates meaning and how these engages the core cognitive activities that make us reasoning, explore, identify, distinguish, compare, make choices and take decisions.

I will also let the umbrella term narrative constructor continue to represent any role that is involved in the conveyance of the narrative as a cognitive and integrated entity as to keep the focus on the making connected to the media-specific and stylistic elements.

If you would like hands-on advice regarding game-specific elements associated with the narrative (according to how the roles and responsibilities are currently sectioned on an organizational level in the industry) on writing plot summaries, quests, narrative branched choices and conversations systems, I recommend reading the writer and narrative designer Alexander Freed´s blog (here) (or on Gamsutra here).

Putting a thought into play

To explain what I mean by putting a thought into play, and how the initial thought matters to what is to become a game, I will take an example from an interview with the writer Dan Houser from 2010 (link to the interview is here), when he describes the initial thoughts that preceded the making of the Wild West open-world game Red Dead Redemption (2010), developed by Rockstar Studios.

”The core idea of the game – to make a fast-paced shooting game with the sensibilities of a fighting game – was very interesting and was done really well… But we love open-world games, and in finishing Red Dead Revolver, we also fell in love with the Wild West. The main thing we wanted to keep and expand upon from Red Dead Revolver was the core sensibilities of the gunplay, which we all really loved. The rest, we wanted to start over and make a game that was vast and epic in scope.”

Since Red Dead Redemption 2 has recently been released, one can see how the initial thoughts that were put into play eight years ago have evolved. From the old concept Red Dead Revolver from 2004, with gunplay as its core mechanic, the thoughts to make a game “that was vast and epic in scope” has reached a new level. What this means is that Houser and his team have given the “open-world game” “vast and epic in scope” a new meaning. And for you who haven´t played the games the new meaning that has been given to the second game was not only to make the world map bigger. What the team did was to move into the details of the game by letting their thoughts give depth to as many objects as possible, giving each a unique mechanic, which created an even more dynamic world compared to the first that met a new “epic in scope.”

Red Dead Redemption 2, Rockstar Games

Red Dead Redemption 2, Rockstar Games

The 7-grade model of causal thinking

To understand how our thinking works when taking off from a thought towards the desired outcome, I´m going to take help from the 7-grade model of reasoning, which is based on the evolution of causal cognition, and where causal cognition is described by Gärdenfors and Lombard (2017):

"(…) a) to predict outcomes based on observations, b) to affect and control events in the world around us, and c) ultimately, to predict causes from effects, even if the causes are not perceivable."

Since the grades in the model distinguish with an increased level of how the causal thinking of the human work (our thinking), and where the first grades only involve the perception of agency. Unless we don´t want to explore the agency from Dan Houser´s motor commands when pressing the key that makes the computer start, I will jump the 1st grade and give you a glimpse of the 2nd, before we are moving on to the more intriguing grades.

The illustrations and descriptions that will be shown are from the post: “A short guide to the 7-grade model” (link to post) that due to the origin of our thinking started long before the Computer Age, which explains the theme, and where the headers defining the grades are from the publication Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017). As I have reserved the right as an artist to see how the model can illuminate the intuitive thinking in the making of games, in the case of research I refer to read the publication, which links can be found at the end of the post.

Grade 2: Cued dyadic-causal understanding

”This grade involves two individuals who take turns in performing a similar action. (…) I understand that your action causes an effect because it gives the same result as my action.”

(Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017, p. 3)

If we return to Dan Houser, the 2nd grade would be as if Houser from seeing a colleague pressing the key on the computer would learn, in the same way as the cavemen learn from each other cracking eggs, how to start a computer.

If knowing that our will to understand is constantly on, which cognitively make us perceive what others do related to our own action. An example of a game where the 2nd grade of reasoning is involved is the online game Journey, by thatgamecompany, where a player can come to another player´s help as to show how to do things, and where to go. From the understanding and learning the player can then transfer what has been learned to another player, who, in turn, pass it on to another player, and so on (which can explain why we like to learn together with others).

Journey, thatgamecompany, Sony Computer Entertainment

Journey, thatgamecompany, Sony Computer Entertainment

From the exchange of thoughts from seeing and learning we can notice how the core cognitive activities depicted in the 2nd grade also depict the core mechanic of collaboration in Journey – which is making the cognitive vehicle of causation intertwine with the rules, behaviors, and goals of a mechanic.

Grade 3: Conspecific mindreading

Since the 7-grade model of reasoning is focused on describing the human thinking, it is also through the 3rd grade one can discern from the results of archeological excavations of Stone Age weapons how the human thinking and understanding has evolved. Though it is easy to be deceived by today´s advanced technology compared to the spears and bows that our ancestors created, it is in the 3rd grade things are getting really interesting. This is when the term mindreading (from the theory of mind) comes into play, and where we can notice how our reasoning of today has many common denominators with our ancestors.

What mindreading refers to is how we understand someone else´s thoughts, and where the 3rd grade depict how we understand someone else´s desires, intentions, and beliefs to be similar to our own, which we infer to be an explanation to someone else´s actions or behavior. As mindreading is not about being accurate when we are coming to an inference about someone else´s thoughts and actions, the fact that we read others' minds is what counts. For a narrative constructor, this is also what you let the characters do in, for example, a film to create surprises and misunderstandings. But when it comes to games, you have to move the perspective as a constructor as to think that it is the player who is doing the mindreading of the objects and elements that you decide to become the parts of the form, which makes the player act and react on when playing. In this way, the 3rd grade is very helpful as to understand how the mindreading works when it comes to understanding how attention, emotions, desire, intentions, and beliefs of others affect us (see the series Narrative bridging on testing an experience on Gamasutra or at the site Narrative construction).

In the same way, as a narrative constructor is letting the perceiver mindreading elements and objects to attend and act upon unexpected things, surprises from reading each other’s minds can also be the cause of misunderstandings in real life. As when inferences turn out to not make sense with another´s person´s desires, intentions, and beliefs, it can be really tricky to even know when working in a large team that a misunderstanding has occurred when most of the things happen inside our heads. As it can be hard to walk around asking everyone “do we understand each other?” we have invented strategies to avoid misunderstandings to occur by, for example, hiring people with the “right” experiences and knowledge. Another strategy is to organize and sectioning the responsibilities so that people know what to do, and through diligent documentation ensure that the communication works. Nevertheless, misunderstandings and conflicts occur. But from the aspect of how the human mindreading works, the question is how we can organize the mindreading to work harmonically in a positive direction?

To answer the question as to understand the forces that are generated by the mindreading, let´s return to Dan Houser and the interview when he says:

”…we love open-world games, and in finishing Red Dead Revolver, we also fell in love with the Wild West.”

What Houser is giving words to are the emotions and desires that everyone who is working with art and entertainment knows as one of the most euphoric moments in a process. When the emotions and desires are put into play, the last thing you want to do is to stop the flow as it is the flow that will become the motivating vehicle to the thoughts that will be giving form to an engaging and dynamic game system. And it is right here (!) the formulation of a clear goal comes into play as to direct the mindreading towards the desired outcome. However, if one would like the forceful vehicle of desires and emotions to spin in a positive direction and not stop, there are a few things to be attentive to:

Make sure that the desired goal is reciprocally shared between everyone who is involved in the process.

If everyone understands the cognitive aspect of having a clear and shared goal it is easier to understand what happens in people´s minds if something unexpected happens. As the desires are the engine to the thoughts that are put into play, a changed goal during the process could become disruptive (an example of a story that ended well when a desired goal met an unexpected change can be found here on Gamasutra, and is about what happened to the director in the making of God of War when someone wanted to change the goal).

Make sure that the mindreading and understanding of other's desires, intentions and beliefs as being similar to ours is not mixed up by gathering people who think the same, have the same opinions, same background, language, norms, and conventions, which can have an isolating effect. As what easily happens in a context based on intuitive thinking (known as a style of thinking sensitive to surprises) is that one closes the door to learning and understanding something new, which can also explain why we sometimes feel that things seem to repeat themselves.

Since the last advice is the trickiest to detect, as who doesn't like to work with someone who knows exactly how you are thinking, and vice versa, which can, if not attentive, easily trigger the kind of cognitive mechanism that can become isolating. But if one would like the process to evolve and not become static it can be good to remember that opinions are not the same as desires as opinions are "closing" and desires are "opening" up for possibilities to unfold/evolve, and therefore it can be helpful to have the desired goal set on learning as to always keep the mind open as a means to understand. If we return to Dan Houser and the team´s desire to make an epic open-world game. Even if unspoken, if the desire hadn't been set on learning, we wouldn't have seen the game evolve. Also, it is the desire to learn and understand that is the answer to how we can organize the mindreading to work in a harmonic/positive direction, as it makes us become better listeners (which you will see later on what I mean).

If we understand the 3rd grade, we can move to the 4th grade, which is also one of the fun grades for a narrative constructor since it is about making people speculate.

Grade 4: Detached dyadic-causal understanding

If the 3rd grade from a constructor´s perspective is the core to the creation of a surprise, the 4th grade is what makes the suspense, which means that you have the perceiver to speculate as to come to an inference. It is here the narrative constructor holds back the perceiver´s desire to get to an understanding (inference, meaning), but where you also bring forth selected information to provide or allow for the player to piece together information.

Since Red Dead Redemption 2 is full of these kinds of cues of elements and objects that point the player´s cognitive activities (mindreading) to trace back in time and space as to understand something about the present. Yet the cues are what to be considered as spoilers, I will choose another example to show what makes us speculate. And where I also refer you to read the series Narrative bridging on testing an experience (here) (or on Gamasutra here), and The surprising scream of learning (here) that are explaining the concepts of surprise and suspense from a cognitive and narrative perspective.

Let´s start with taking a look at how the 4th grade is described in the short guide to the 7-grade model by returning to the cavemen:

“Sometimes we do not perceive another’s presence, but only the traces of them. (…) Being able to reason from effects to non-present causes seems to be unique to humans.”

(Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017, p. 3)

(1).png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

In the picture above we can see the traces from the cavemen that were cracking eggs in the 2nd grade. Since we are familiar with the cavemen, the traces are enough to trigger our mindreading to come to an inference of the cavemen´s presence in the past to be the cause of what we see in the present. But in the same way as with the 3rd grade that it isn´t by the accuracy of the results from the mindreading that counts but the fact that we do it (as who knows if it could have been someone else cracking eggs), I will choose a similar picture, as to show how a narrative construction triggers the perceiver´s cognitive activities to come (or not) to an inference.

Death Stranding, Kojima Productions

Death Stranding, Kojima Productions

The prints in the mud (above) are from a trailer about the upcoming game Death Stranding, by Kojima Productions (link to trailer). As the trailers have engaged a large group of people to speculate about what the game will be about, the trailers have done what trailers should do. Or have they? As you will soon see, not everyone agrees to what a trailer for an upcoming game should do.

From knowing the 4th grade, we can see how the designer Hideo Kojima has triggered the perceiver´s mindreading to imagine from the pieces of information, delivered by the trailers, to work as the prints in the mud to engage the perceiver´s causal thinking to come to an inference. It is not strange that the mindreading of the pieces of information is ending up reading Kojima´s mind, as it is there the answer to the game resides. The intriguing thing is how the speculations from the breadcrumbs Kojima has put "into the screen" have made Kojima respond in an interview (here) why he is not going to reveal what the game is about, as follows:

“We live in a time of social networks. In this time, people just want immediate answers, but not only answers, but they also want to know what they feel. This is good, this is bad. This is a game I should like. This is a game I shouldn't like. They want answers for what they should think.”

Since the trailers have raised curiosity for the upcoming game, it might seem a bit odd that Kojima feels an urge to state something that would be like telling people why Christmas gifts can´t be opened in June. But what the statement reveals is Kojima´s discontent with the current promotion of games in the game business, which is to show what the game is about. This explains why Kojima is also saying:

“It’s like a math problem, where knowing the answer is not that important. The important thing is the process of getting to the answer.”

As it seems to be contrasting meanings that Kojima is addressing, and that we know from the 3rd grade depends on how we are reading other's minds as being based on similar desires, intentions, and beliefs as our own. If we look at the trailers that could be described as breadcrumbs leading to Kojima´s mind, it reveals how Kojima has put the finger on different experiences regarding the use of trailers. This, in turn, illuminates how different experiences can generate different desires. Whether the differences Kojima is giving words to are internal or external, we can´t tell. But as it is a dilemma that many are experiencing that somewhere during the process there is someone that is expressing an opinion that clashes with the desired goal we will take a closer look at the cognitive and narrative vehicles that are put into play illuminated by Kojima.

If someone, for example, is thinking about the promotion of a game as a product that shall provide all the functions that are expected in a manner of making the customer feel safe when buying a car, television, fridge, oven, etc. What happens is that the player turns into a customer, which can disrupt the thoughts that have been put into play towards the desired goal. The reason for the disruption is that the constructor, in the same manner as the perceiver, is reading the perceivers' minds. And if the mindreading is set on building an experience that is to surprise and engage the player, a possible trust issue that leads to showing the product should be addressed from the start. Because, when a team puts their thoughts into play that are to become the system of elements that creates a causal and dynamic network of links, it can disrupt the construction to reach the desired outcome as a desired goal also includes the goal to be reciprocally shared with the perceivers. With the 3rd grade in mind that is directing the constructor´s mindreading to engage the players, as to be players thus the mindreading needs to be re-directed if making the players into customers as to gain, for example, trust in a product. And if we look at what the reviewer says about Kojima, it doesn't seem to be a lack of trust that would require Kojima to show what the game is about:

”By not offering a concrete concept in the public marketplace of what Death Stranding is just yet, Kojima is causing fans to openly converse about the potential it holds rather than regurgitating the details offered by development studio, thus keeping its mysteries alive while also ensuring it remains at the forefront of potential players’ discussions.”

The reviewer rather reveals the different experiences that form the beliefs and expectations about what a trailer should do or look like. And when Kojima is criticizing the current promotion to show rather than involve, it might have something to do with the changed perspective on the player to become a customer that would make Kojima into a salesman instead of a designer. As you don´t convince as a designer but engage, the desires from promoters and designers will clash, which should not be mixed up with that the designer doesn't want to sell the game. Since it is given that you can´t reach the desired goal if you can´t make the mechanics spin, the money aspect is always a part of the process. But it should not become the desired goal but stay as a constraint that one relates to during the process (in the same way as the players relate to their constraints by making up plans to save money as to make the desires to meet, which we refer to as the expectations).

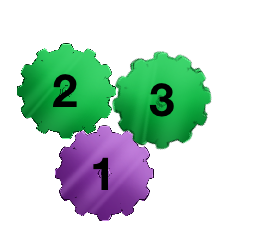

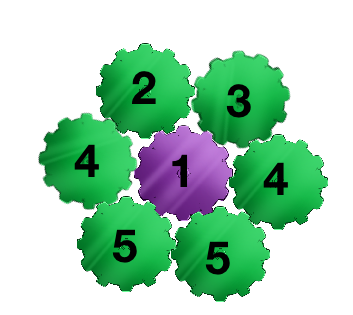

Putting cogwheels into play

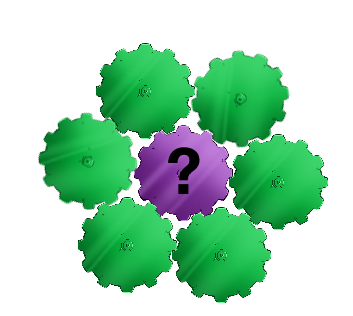

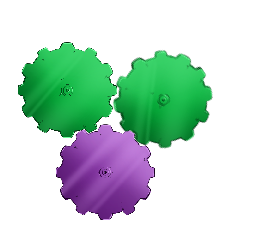

However, if we take a look at the construction from a narrative and cognitive perspective to understand what it is Kojima is doing when triggering the players' core cognitive activities to speculate about the upcoming game from seeing the trailers. To show how a constructor is holding back and bringing forth the information as to engage the perceivers´ mindreading, I will use the two cogwheels below as to depict how the thoughts are generating mechanics and meanings:

If we start with the green cogwheel meaning, it represents a piece of information that Kojima is putting “into screen”, which could be anything from a beat, event, sequence such as footprints in mud, characters, appearance, facial expressions, equipment, behaviors, reactions, gazes, something spoken or written, environment, climate, weather, light, sound, topography, etc. What Kojima does from a cognitive perspective on the narrative is that he is holding back and bringing forth the pieces of information. From the pieces of information, the inferences, the players try to create meanings, which could, if the inferences are proved to be correct, explain the mechanic. As if the players can figure out how the cogwheels of meaning relate to the mechanic, from the causal understanding the players can figure out how the game will play – the gameplay. And from sharing and comparing the different meanings with other players the engagement increases, which explains what the reviewer describes as Kojima is “keeping mysteries alive.”

If we return to possible dilemmas that can occur, from a narrative and cognitive perspective, in the construction of a trailer. One problem is if believing that the pieces of information can be randomly spread to engage the perceiver´s imagination. Since the meanings inferred to the pieces of information will become the expectations that need to be met, it will immediately be noted if the breadcrumbs are disorientating the perceivers, since the inferences from the mindreading will be proven wrong. But a common explanation to what can cause mistrusts is when a trailer is making the players create meanings about the mechanic and the gameplay that later on turns out, when the game is released, to not even exist. And if the experience of promoting a game where mistrust has occurred, the belief can take root that players want to see the gameplay. Since the problem often resides in that people don´t know how the narrative and the "cog(nitive)wheels" work and where for example the tradition of pitching ideas before even knowing what the mechanics will do can easily create a belief that the same approach works on trailers.

However, concerning not revealing too much about the game in a trailer and where Kojima says “it´s like math problem”, Kojima also explains in the interview why he is constructing the trailers as he does, as follows:

“I don’t want to take away the most fun part for the players.”

And for you who have read an earlier post 2 plus 2 but not 4 (link to post) the filmmaker Andrew Stanton (Toy Story, Finding Nemo, etc.) is saying something similar to Kojima about the clues to engage an audience is to not give the audience the “4” (the answer) but instead make them do “2 plus 2“, as:

“The audience actually wants to work for their meal, they just don´t want to know they are doing that. That is your job as a storyteller, is to hide the fact that you are making them work for their meal”.

In this way, Stanton confirms Kojima´s statements about that it is the process that matters, and not the answer. But what we also can see is how Stanton´s and Kojima´s analogies are also confirmed by the 4th grade that shows the motivating vehicle of causal understanding and how our mindreading works when we are following breadcrumbs as to come to an inference - making meaning.

Grade 5: Causal understanding and mindreading of non-conspecifics

A game designer who is like a reference book to how our thinking works and who is an excellent guide to explain the last grades in the model (5-7) is Fumito Ueda. The three games Ueda is known for are Ico (2001), Shadow of the Colossus (2005), and The Last Guardian (2016), that builds on a strong relationship between the player´s character and its companion. But Ueda is also talked-about as being secret and mysterious, which can be noted in almost every interview (that are also said to be rare). However, if you are looking beyond the mindreading of Ueda as a person, whereby people are trying to understand the magic and mysteries in the games by mindreading Ueda. But as you will soon see, Ueda is crystal clear about how he is thinking in the making of games.

How to follow the mindreading towards a desired goal

It is, in particular, Ueda´s unique skill in mindreading that I would like you to notice, which we can see in an interview (here) when Ueda describes how the thoughts were put into play in the making of The Last Guardian.

“Once we were done with Shadow of Colossus there was a moment when I reflected on what we really wanted to communicate and portray in that game. For me it was the main relationship between Wander and the girl, but after the release, I read a lot of feedback from players who were touched by the game, and they said that the relationship between Wander and the horse was the most important and appealing – we got the sense that this was what most people felt. I thought OK, if that’s the case, there are a lot of mechanics from that relationship that we could heighten and expand on. That’s where The Last Guardian came from.”

From what Ueda says, we can see how he is making the desired goal become reciprocally shared when he, together with his team, and the players, are setting the desired goal. And based on what Ueda says (above), I will take it step-by-step and start showing how he is setting the desired goal.

Setting the desired goal

Step 1

When Ueda says: “We reflected on what we really wanted to communicate and portray in the game,” Ueda is formulating the thoughts that are to be put into play to set the desired goal for himself and the team.

Step 2

As we have learned from the 3rd grade by how we read someone else´s desires, intentions, and beliefs, Ueda reflects upon his beliefs, related to the players´, when saying: “For me it was the main relationship between Wander and the girl,.” But how Ueda shows how he is listening to what the players say and from comparing his beliefs with theirs can be seen in the following line: “…but after the release I read a lot of feedback from players who were touched by the game, and they said that the relationship between Wander and the horse was the most important and appealing”.

Step 3

Based on the comparison of beliefs with the players, Ueda evaluates the players desires with the team´s desires and beliefs, and where they come to an inference: “we got the sense that this was what most people felt”, which becomes the desired goal: “I thought OK, if that’s the case, there are a lot of mechanics from that relationship that we could heighten and expand on. That’s where The Last Guardian came from.” In this way, we can see how Ueda, together with the team, sets the desired goal by adjusting beliefs from what the players say as to make it reciprocally shared (the activity also shows the difference between attending to what the players want and what the players desire, which can easily be mixed up).

From the process of mindreading and the setting of the desired goal, three elements are put into play to become the parts of the desired form for The Last Guardian:

1. A mechanic of a relationship.

2. Two elements, a human and an animal, are added to the mechanic (1).

Simply expressed, what we could see is how Ueda, from listening to the players, changed his beliefs and added a new experience, which is what we do when we learn. And where we can see what it means to have the desire set on learning to keep the mind open as a means to understand.

Since it is through mindreading that we can understand attention, emotions, desires, intentions, and beliefs of others; to understand what is happening next in the process in the construction of The Last Guardian I will turn to the 5th grade so we can understand how Ueda by mindreading is giving meaning to the mechanic and the elements that are to become the core of the game.

From the short guide of the 7-grade model, the descriptions and illustrations of the 5th grade look as following:

”We sometimes have a dyadic-causal understanding of the actions and intentions of other species, although their motor actions and cognitive processes are different from ours. (…) The difference, between Grades 3 and 4 on the one hand, and Grade 5 on the other, is gradual and depends to a large extent on the experience of the behaviour of other species. (…) The mapping is a matter of degree, though – we find it easier to read the causal forces in the mind of a chimpanzee or a dog than that of an iguana.”

(Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017, p. 5)

What the 5th grade shows is how strong our causal understanding is that makes us even read the mind of animals as if they would share similar desires, intentions, and beliefs as ourselves (shown in the 3rd grade). But as Gärdenfors and Lombard (2017) note, depending on our experience and familiarity with the animals it can be easier for us to read the mind of a chimpanzee or a dog than an iguana. However, what the 5th grade can explain is if we see an animal that is hurt we can use a form of “empathy mirroring” and read the mind of the animal as to understand how for example a bird feels that is hurt, which doesn't mean that inferences are correct. But where the fact that we do it is what matters from a cognitive and narrative perspective.

Let´s return to Ueda´s mindreading as to see what he says (link to interview):

“We found out that a lot of people are very curious and interested in animals. So we felt like if we introduced an animal or living creature in this game that hopefully, it would appeal to a wider audience. That is something that really kicked off our brainstorm in the idea and formation of The Last Guardian."

In another interview (here) Ueda tells about the formulation of the concept:

”When I was formulating the concept of The Last Guardian, one of the things I looked at was the relationship between people and animals, and I thought this was something that I wanted to build a game around. Most people really relate to animals – they find them cute and easy to bond with – so that relationship was the primary focus. The reason I chose this core theme is that I wanted to appeal to as many people as possible, knowing that it would resonate with many players. As a result, I hope some elements of the boy and Trico’s expressions may well come across as ‘charming.’”

From what Ueda says, the elements of the mechanic have been given meaning by becoming a boy and an animal called Trico.

The Last Guardian, by gen Design, Sony Interactive Entertainment

The Last Guardian, by gen Design, Sony Interactive Entertainment

Grade 6: Inanimate causal understanding

To explain how Fumito Ueda continues the mindreading to give the elements and objects a form. The 6th grade depicts our causal understanding of a physical force of an inanimate object. Since Lombard and Gärdenfors suggest that the 7-grade model can be applied to other technology and tools which have evolved from our ability to reason, we can move from the Stone Age, and the making of weapons, to the Computer Age and the making of games.

From the lower grade of reasoning (1 and 2) we can understand from Houser turning on the computer or to cracking a nut with a big stone the causal relations as a physical force. Another example of a physical force, depicted by Gärdenfors and Lombard (2017) is that we can feel the gust of wind, connect the wind´s causal relation to an apple that lies on the ground, and infer the wind, as a force, making the apple fall from a tree. Just how advanced our causal understanding of a physical force is, can be seen in how we can “move" a force from wind to another domain that has made us invent sails for boats and “blades” for windmills.

If we move to the Computer Age the same causal understanding can be seen in the creation of mechanics, from which rules, behaviors, and goals we are simulating the physical force of a wind by the making of a wind-mechanic, which can not only blow apples from trees but also blow off hats from people´s heads. In the same way that we can create a wind-mechanic, we can also see how Ueda is creating a relational mechanic between a boy and Trico (and where Houser, for example, created a bond between the player and its horse in Red Dead Redemption 2 that was converted into a "horse-care-mechanic"). But as a force doesn´t have to be physical but can be stored and planned to happen over time, we need to move to the 7th grade as the complexity increases. But before we move. If returning to the wind to understand the complexity by how our causal thinking and understanding work. From our ability to discern the wind as to exert a force, and from seeing how the understanding of force is applied to other domains, we can also see how the force transmission (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017) is in play when we are moving mechanics from an old game to a new, as to use the force when giving new meanings to objects and elements in a system (or building an engine).

Grade 7: Causal network understanding

How the force transmission is depicted in the short guide on a more advanced level, and where the 7th grade involves all aspects from the grades (1-6) that are mapped onto each other in a never-ending pattern. The way the 7th grade is illustrated in the picture below is from the creation of a trap, which discloses the complex reasoning behind the construction of a trap that covers all grades.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

But since there is no hostility involved in the creation of a game as the one depicted above, we can use the force of a trap as a metaphor to the force of seizing the perceivers´ attention and emotions. Even if the complex reasoning behind the setting of a trap is the same as Ueda´s, regarding the causal understandings of networks. The huge difference, though, is that the desires, intentions, and beliefs between the men behind the cliff are not reciprocally shared with the caveman that is about to be caught (which makes me once again refer to the 3rd grade and why a shared reciprocity matters to the desired goal, and why it requires an openness to learning).

Making meaning of the parts towards the desired goal

Since Ueda moved a mechanic of a relationship from an old game (Shadow of the Colossus) to The Last Guardian, it is very helpful to see the cognitive activities and behaviors as a force and how a mechanic connects hardware and our reasoning to become a united force where all parts are playing towards the desired outcome. To show what I mean I will let Ueda be our guide in the building of The Last Guardian.

If we continue from the steps (1-3) in the 5th grade where Ueda set the desires to be shared and based on the desires from the players, Ueda moved the mechanic of a relationship from an old game and added two elements of a boy and a beast, called Trico. To follow how the thoughts are giving meaning (constructing a narrative) to the mechanic and elements, Ueda says about Trico as following (link to interview):

Step 4

“He is part dog, cat, bird, others. But we wanted him to be believable. We wanted you to feel like you could reach out and touch him. (…) Through textures. We looked at fur and different kinds of skin. After many experiments, we discovered that feathers offered the best believability. They also have a soothing quality.”

From the text above, what Ueda and his team desire the player (“you”) to feel, is a desire to reach out and touch Trico, which generated following meanings to the causal network between the mechanic and elements.

1. A core mechanic of a relationship

- Boy (2) touch Trico (3)

2. Element (Player´s character)

- Boy

3. Element

- Trico (name)

- Dog, cat, bird.

- Furs and feathers - stylistic elements of texture supporting “touch” (1).

Let´s continue to another interview (here), as to show how Ueda and his team continue to give meaning to the core mechanic and the elements, which make us move to:

Step 5

“The idea that the boy hangs on to Trico and moves to places that he would not have been able to go [to] by himself is the main concept for this game,” (…) “And the contrast between the small movements that the boy makes by himself and the large dynamic movements that the boy makes with Trico is at the heart of the game, and that has not changed since the very beginning.”

From what Ueda´s says we add to the list:

1. A core mechanic of a relationship

- Boy (2) touch Trico (3)

- Boy (2) hangs on Trico (3)

- Small movements (2)

- Large movements (3)

2. Element - Player´s character)

- Boy

- Small

3. Element – Player´s companion

- Trico (name)

- Dog, cat, bird.

- Furs and feathers - stylistic elements of texture supporting “touch” (1).

- Large

Step 6

As Ueda mentions (in step 5): “the boy hangs on to Trico and moves to places that he would not have been able to go [to]” (regarding the boy), it opens up for a new element to be added, which concerns the level and world design, we add:

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

4. Element – Level and World design

- Places where the boy (2) can´t go to, which requires "large dynamic movements that the boy" (2) "makes with Trico" (3).

The core mechanic of a relationship (1) and the elements of a large Trico (3) that is making large dynamic movements (1), and the small boy (2), who´s making small movements (1), gives the core mechanic of a relationship (1) a depth by extending the mechanic with a puzzle that involves the level/world design (4), generated by the large and small movements (1). This is because Trico can´t get through the small openings in the world (4), which the boy can. But where the boy can´t get to the high cliffs and large buildings (4) as to make it to new places. In this way, one can see what Ueda means with “The heart of the game” (from step 5) by how the elements are circulating and cognitively intertwine with the core mechanic and the desired goal, which Ueda is giving meaning to by deepening the relationship between the boy and Trico.

As the last example, I just want to show how Ueda is giving meaning to the constraints as to enable the engine (the hardware) to run the elements towards the desired goal (link to interview):

Step 7

“We need to create using technical specifications that put limitations on what we create, (…) It’s really about trying to find the most effective way to visually express what I would like to do: the outcome is what you see. (…) We sometimes resort to the hazy visuals because we can’t illustrate beyond a certain point.”

Based on what Ueda says (above), we can add a new (stylistic) element to the list that concerns visual effects.

1. A core mechanic of a relationship

- Boy (2) touch Trico (3)

- Boy (2) hangs on Trico (3)

- Small movements (2)

- Large movements (3)

2. Element - Player´s character)

- Boy

- Small

3. Element – Player´s companion

- Trico (name)

- Dog, cat, bird.

- Furs and feathers - stylistic elements of texture supporting “touch” (1).

- Large

4. Element – Level and World design

- Places where the small boy (2) can´t go to and requires “large dynamic movements that the boy" (2) "makes with Trico”(3)

5. Visual effects (Haze)

- When a small boy (2) makes small movements (1), haze (5) on large buildings/cliffs (4).

- When large Trico (3) makes large movements (1), remove haze (5) on large buildings/cliffs (4).

To meet “the heart of the game” (see step 5 - the contrasts regarding large and small movements) the visual effect of haze (5) is used to enable the computer to run the details, at the same time it is making the player/boy (2) able to cognitively navigate through the levels/world (4). When the focus is on small movements, haze covers the large objects, and if the boy (2) needs Trico to move to the large objects, the haze is moved from the large objects to direct the player´s attention. In this way, the stylistic elements cognitively and technically support the meaning-making and constraints to make all the parts play towards the desired outcome.

Rounding up

After reading the interviews with Fumito Ueda, it seems like no matter how clear Ueda is about how he is thinking in the making of a game, it is like people can´t hear, as right after they return to ask if Ueda is intentionally mysterious. Or, when the haze was brought up (here), one couldn't believe that the dreamlike world could be as simple as a technical rendering issue, and where the interviewer wondered where Ueda got his ideas from that generated the style and buildings, which Ueda responded to:

“I don’t do a lot of study – I haven’t really travelled to see anything as reference. I don’t do a lot of interviews, but I get this question all the time! We just go from our imagination. Although we create very large structures, it’s all down to the little details that make it seem as though they really exist. I think those are the things you’re referring to when you say the worlds are dreamlike.”

However, when coming across the following words from Ueda, I couldn't feel anything but a deep empathy for his struggle to be understood (link to interview):

"As a person, I'm very practical. But I really need to believe the world I'm creating exists, so I need to make myself believe by getting inspiration from music or books that [centre around] fantasy worlds. A lot of people believe that I'm such a fantasy person and living in that fantasy world all the time, but there's a huge gap between people's perception of myself and me as a person."

Though our desires constitute a strong engine that motivates us to believe that what appears as too simple can´t be true, which makes us continue the search for a meaning, I hope the 7-grade model of reasoning can make us get in contact with what is going on in our heads as a means to recognize how our attention, emotions, desires, intentions, beliefs, connect to our learning. With these words, I would like to thank you for reading and let Gärdenfors and Lombard (2017) round up by giving their description of the 7th grade, which explains in short what “is unique to the human mind of today”:

“The ability to generate inter-domain causal networks, use network understanding to speculate about potential outcomes, test and re-adjust our imaginative hypotheses, and to shift attention from one target to another, while keeping in mind the ultimate goal (e.g., subsistence) over an extended period of time is unique to the human mind of today.”

If you are interested to see how other designers are sharing their thoughts, I recommend among others to read what Lucas Pope is saying, who is an indie game developer that has been working alone in the making of games such as Papers Please and Return of the Obra Dinn. To follow the process, just find the part where the desired goal is expressed, and then you take it from there (link to the interview is here on Gamasutra).

Take care and may the force of the desire to learn be with you.

Katarina Gyllenbäck

Illustrations by Linnea Österberg

Illustrations of cavemen by Emese Lukács

Continue to:

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

References:

Gärdenfors, P., Lombard, M., (2017). Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans. In the Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95. p.219-234

Exploration:

Explore your imagination - For you who would like to explore your imagination from the grades of causal cognition.

Very related readings:

A short guide to the 7-grade model of reasoning (at Narrative Construction)

Part 2 Narrative bridging on testing an experience - About curiosity, surprises and suspense.

Part 3 Narrative bridging on testing an experience - About learning, engagement, and emotions.

Part 1 Don´t show, involve - About setting a premise towards a goal.

Part 3 Don´t show, involve - About creating meaning/meaningful experiences.

2 plus 2 but not 4 - How to engage the perceiver´s cognitive activities (referred to in the 4th grade).

Related readings:

Narrative patterns of thinking

The surprising scream of learning

Where I work there are no conflicts

Interesting readings:

Directing from the sidelines - About the rise of concept teams in Japan´s game industry.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like