Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

The 'Interactive Empathy and Embodiment' framework is an innovative, sensory design approach to game design founded on traditional craft, which promotes empathy and hopes to nudge the industry in a more self-aware and conscientious direction.

The Interactive Empathy and Embodiment (IEE) framework is an innovative, sensory design approach to game design and interactive media that uses traditional craft techniques to heighten the player-audience's physical experience of gameplay.

You can think of sensory design as working inside-to-outside, whereby the design process starts by defining the player’s kinaesthetic state (referring to physical activity-based aesthetics) before orchestrating external solutions that evoke this predetermined experience. Approaching the game development process from a sensory perspective—as opposed to a rules, objectives and mechanics-driven approach—enables readers to actively explore solutions to the following ideology:

What if empathy, not conflict, was the organizing principle of game design?

2020 was a challenging year for everybody, which is why the 2-part book is unreservedly FREE (with the possibility of giving a donation), since the need for interactive experiences that promote empathy and reconciliation is at an all-time high. The IEE framework therefore hopes to nudge the industry in a more conscientious direction and provide game design in a format that is accessible to everybody.

The following is an extract from the Introduction of Volume 2: Framework Walkthrough. Volumes 1 and 2 are available as a FREE download on Gumroad.

INTRODUCTION

Coming from a traditional figurative art background, my perspective of game design has always been at odds with convention: as a process that starts by the definition of rules, objectives and game mechanics for generating gameplay. The aesthetics of such a game design approach are treated as a byproduct of the rules and mechanics and have the lowest priority in the development sequence known as M-D-A (mechanics > dynamics > aesthetics). Many developers feel that this is the only way that interactive experiences can be produced.

As discussed in Volume 1: Shape Language and Composition Fundamentals (IEE Fundamentals) of this framework, a common conceptual error is to define the “A” for aesthetics to mean visual aesthetics. Video games are inherently an interactive medium and their artistic structure is rooted in player-activity, which requires movement. So could aesthetics be approached from a different angle to upend the established M-D-A structure?

Gesture drawing

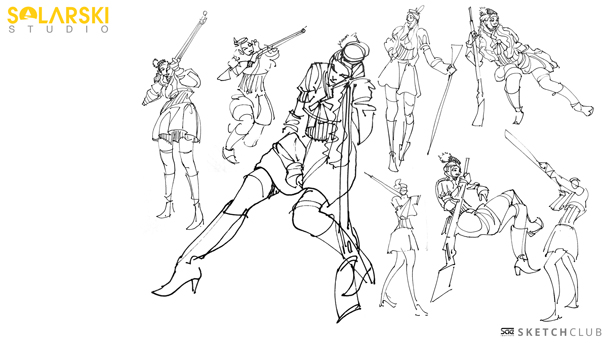

My personal approach to game design is greatly informed by gesture drawing—the practice of drawing a live model within a limited time, which can be as short as 30-seconds or 1-minute (examples below). The relevance that gesture drawing has to interactive media is that it similarly involves a person (player) observing a dynamic subject (gameplay) and making split-second decisions before reacting with corresponding pencil strokes (controller inputs). Just like a player reacting to on-screen activity and directing their avatar’s movement via an analog stick, an artist captures life and movement using a minimalist set of lines of varying aesthetic quality. In both cases, the artist and player have a unique and personal opportunity to embody the aesthetics that they perceive visually—physically channeling the subject’s energy through the act drawing/playing.

The aesthetic quality of every line in these 1, 2 and 5-minute gesture drawings, by Chris Solarski, must convey the dynamic energy of the model.

My gesture drawing experience—more than any other artistic practice—has led me to develop a methodology that approaches the game design process with an emphasis on aesthetics over rules and game mechanics. Titled Interactive Empathy and Embodiment (IEE), the framework promotes a high-level sensory design approach for game design, although the concepts are equally relevant to interactive media like virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and cross-reality (XR).

The evolving definition of video games

The IEE framework’s sensory approach accordingly defines “video games” as interactive experiences deliberately designed to evoke a kinaesthetic response. The player’s kinaesthetic response may be the exhilaration of victory, happiness, sadness, and any other aspect of human experience. You may feel that this all-encompassing definition is too broad and that some gaming genres can be de facto classified as “video games” (i.e. role-playing games) and other genres (i.e. walking simulators) as “not games” or “interactive art.” The broader counter argument contends that industry pioneers helped shape our common perception of what video games are/are not, but our understanding of the medium and its aesthetic scope is continually growing and evolving. The mainstream definition of video games will therefore continue to expand accordingly until “video games” is comfortably associated with the entire range of interactive experiences available to us—as suggested by game designer and academic Eddo Stern, who expressed the following statement at a games-as-art panel discussion at swissnex San Francisco in 2012: “don’t change the name, just wait.”

Deepening the in-game experience

It used to be that retro game box art would present richly detailed Hollywood-style action and effects but the in-game product, while still entertaining, delivered an unspectacular pixelated experience. This is no longer the case, with in-game graphics matching the fidelity promoted on their covers.

Retro game box art promised Hollywood-style effects but the in-game product was delivered pixel graphics, such as Defender (1981) by Williams Electronics. [Images from 8-bit Central]

Dramatic devices like non-interactive cutscenes are arguably the new retro box art—designed to emotionally-embellish in-game experiences that comparatively remain narrow in aesthetic scope.

Cutscenes follow the same convention as retro game box art—promising emotionally-resonant experiences while the in-game product is reduced to exploring a narrow aesthetic range. Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End (2016) by Naughty Dog

This is not to say that titles like God of War (2018) and Uncharted 4 (2016), pictured above, are bad. Quite the opposite. They are at the cutting edge of what’s currently possible in game design. However, to paraphrase and expand on Anita Sarkeesian's valuable guidance: it’s both possible, and even necessary, to enjoy media while simultaneously being critical of its problematic aspects and creative weaknesses, so as to help identify the industry’s next level of progression.

The IEE framework aims to help remedy this disconnect between cutscenes and the in-game experience by offering design tools for shaping the in-game kinaesthetic experience, thus bringing the emotional fidelity promised by cutscenes into the hands (and bodies) of players during gameplay. To achieve this, designers will be required to think less about what players will be doing and more about the transient kinaesthetic nature of the person they will become while playing.

Physical, non-verbal communication

The act of defining (or re-defining) video games is necessary if we wish to expand the medium’s artistic potential. A kinaesthetics-driven approach is an important aspect of this re-defining process because a person’s outward-facing physical state is crucial for communication and generating empathy. In fact, around 90% of communication involves physical components like facial expressions, gestures and posture, with only 10% given to verbal communication. And what sets interactive media apart from other storytelling forms is the active participation of the audience. The very word “interaction” implies an interrelated and inherently kinaesthetic activity between people, or between a person and virtual entities.

This interaction is immensely significant because it means that designers have the unique opportunity to communicate with a player-audience through the tactile senses of touch and movement—the distinguishing ingredient of interactive media, which sets it apart from other art forms. Consequently, while cinematographers abide by the principle of show, don’t tell, interaction designers must one-up their craft with the principle of move, don’t show.

It’s by no coincidence that the word “emotion” has deep etymological links to “motion”—originating from the Latin word “emovere” (“movere” meaning to move). And, as the influential choreographer of modern dance, Martha Graham, was fond of saying: “movement never lies.”

By activating the player’s body we can affect their mind and emotions. The IEE framework therefore focuses on the player-audience’s kinaesthetic sensations with the aim of heightening embodied empathy towards avatars, objects and activities within the intangible virtual worlds that they inhabit. This is why the term player-avatar is often used throughout the framework, to emphasize the heightened kinaesthetic connection between the player and their virtual representation in the game world.

Mirror neurons

Kinaesthetic expression will remain essential even after science perfects neuro-control (allowing the human brain to directly interface with a computer). The work of David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese—see Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience (2007, Trends in Cognitive Sciences)—among others, has demonstrated how mirror-neurons give us the ability to experience empathy towards observed subjects even when no overt movement or contact is involved. This extends to the seemingly “passive” experience of appreciating a static artwork like a painting or sculpture.

The video montage linked below of parkour and skateboard “fails” will give you a heightened sense of your mirror neurons at work. While watching the video, pay close attention to sensations in your body. You’ll find that, not only are your muscles triggered by each impact, but that the sensations you feel relate to the specific body parts being impacted.

Pay attention to the sensations in your body in response to each impact. [Clips sourced from YouTube videos by FailArmy and RibeiroSK8]

Keep in mind that what you just experienced was triggered by non-interactive video clips viewed on a static, two-dimensional digital display. There is no overt interaction between you and the activity occurring on-screen and yet you kinaesthetically empathized with each athlete to a lesser or greater degree.

This proves that even media that we regard as passive experiences are constantly acting on our physical senses, although the effects are more often experienced on a subtler, subconscious level. This neurological phenomenon suggests that interaction designers have the potential to use virtual proxies to trigger kinaesthetic sensations in specific body parts of the player-audience. Similar kinaesthetic sensations occur in players of classics like Pong (1972), who “feel” the collisions between the paddle and virtual ball, although the subconscious begins bracing itself for impact as soon as it anticipates that a collision will occur.

The must-watch rubber hand illusion (also known as the body transfer illusion) further proves that we can think of our bodies as merely incidental to our sense of self. Like Mario’s hat in Super Mario Odyssey (2017), our body is ready and willing to embody any subject that we observe. This tenuous relationship between mind and body is partly the reason why players of The Walk VR (2016), pictured below-left, automatically embody the French acrobat, Philippe Petit, who performed the original tightrope stunt featured in The Walk (2015) film, pictured below-right.

From left: players of The Walk VR (2016) automatically embody Philippe Petit, the tightrope-walking protagonist of The Walk (2015), even though they are playing in the safety of closed room. [Images by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment]

Our bodies are compelled to react, and the more experience we have with an activity or object the greater the kinaesthetic empathy.

Like Neo’s body physically reacting to virtual stimuli in The Matrix (1999), by the Wachowskis, neuro-controls will not invalidate the need for interaction designers to shape the kinaesthetic experience of players.

Neuro-controls cannot nullify these sensations since kinaesthetic responses are a natural human response mechanisms. Player’s will always need some form of physical outlet, like Neo’s body convulsing when “jacked” into the virtual matrix. A completely passive physical state is not possible outside of advanced meditation.

The question will therefore forever remain: what kinaesthetic impact do interactive experiences have on the player-audience—irrespective of the development approach?

The Interactive Empathy and Embodiment framework serves to give developers the tools to begin answering this big question. And, just like the 2000+ years of traditional craft that have come before games, the principle tools to solving this question involve the humble practice of drawing and two particular traditional craft techniques: shape language and composition. The fundamentals of these techniques are extensively examined in IEE Volume 1: Shape Language and Composition Fundamentals.

A work in progress

Please note that Interactive Empathy and Embodiment is a work in progress. It may be the culmination of 15+ years of research, practice, and game development (not to mention the 2000+ years of traditional craft techniques on which it is founded), it nonetheless requires extensive testing and further development. I am aware that the framework has diversity and inclusivity issues and I have yet to investigate how my work holds up against valuable research in the fields of data feminism, disability, black, indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC), and LGBQTIA+, which are outside my immediate area of expertise. I therefore humbly welcome critiques and feedback that will help expand the framework’s scope to rightfully acknowledge an even wider range of peoples and historic contributions to traditional craft. The advantage of IEE being in a download-able PDF format, over a conventional book, is that it can readily be updated.

I would also be grateful for assistance with proof-reading, editing and translations, since I hope to have the framework available in multiple languages.

About the author

Chris Solarski’s started work in video games at Sony Computer Entertainment’s London Studio as a character and environment artist before making a career-defining detour into figurative oil painting. The unusual mix of game art and classical art eventually resulted in Chris authoring Interactive Empathy and Embodiment—a sensory design framework that adapts traditional craft to interactive media with the aim of heightening kinaesthetic empathy and embodiment. Chris has also authored two books on game art and storytelling in games that are endorsed by the likes of Assassin’s Creed founding member Stéphane Assadourian, and Cyberpunk 2077 level designer Max Pears. Chris’ work has been described as gaming’s equivalent to Robert McKee’s screenwriting classic, Story (1997), and Joseph Campbell’s universal storytelling structure. Chris has had the pleasure of presenting at the Smithsonian Museum’s landmark The Art of Video Games exhibition, Disney Research, SXSW, Google and FMX, to name a few.

Please visit solarskistudio.com for more info.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like